Who? Fantômas!

A woman found brutally murdered in a locked room. A chemically preserved corpse discovered in a steamer trunk. An audacious robbery committed by a masked and tuxedoed thief in a grand Paris hotel. Nothing connects these crimes, only the suspicion that the same perpetrator committed them all. Who? Fantômas!

Written between the years 1911 and 1914 by the writing team of Marcel Allain and Pierre Souvestre, the Fantômas serial ran for a total of thirty-two novels. In that time, the title character eluded the forces of justice and committed increasingly daring crimes to satisfy an urge for “beautiful-compulsive” violence. To read a Fantômas novel is to enter a fast-paced, bewildering world loaded with violent imagery. Where ultimate evil is never defeated, but escapes every time.

Fantômas was the prototypical supervillain. He had no goal beyond the desire to wreak havoc, a hybrid of Edmond Dantès (the Count of Monte Cristo) and the Joker; not so much a character as a phantom, an invoked spirit: the Lord of Terror, the Master of Crime, the Genius of Evil.

From the opening exchange of the first novel, there is no doubt as to his powers:

“Fantômas.”

“What did you say?”

“I said: Fantômas.”

“And what does that mean?”

“Nothing… Everything!”

“But what is it?”

“Nobody…. And yet, yes, it is somebody!”

“And what does the somebody do?”

“Spreads terror!”

The novels’ popularity cut through social classes. They were read avidly by the public, as well as championed by the surrealists who saw in the series a predecessor to their own work and a key to the imagination. Raymond Queneau, Blaise Cendrars, Magritte, and Pablo Neruda all admitted to being fans. Guillaume Apollinaire called the series “inestimably rich” and suggested that in order to achieve the full poetic effect the novels should be read straight through as quickly as possible (a habit he also recommended for the works of Dumas and Paul Féval, the originator of the “cloak-and-dagger” genre and the author of a series of vampire novels that predate the works of Bram Stoker). James Joyce described the series simply as, “Enfantômastic!”

However, Allain and Souvestre had not set out to create anything of cultural import when they began the series.

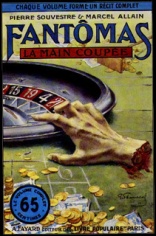

The pair had met while working for the automotive magazine Poids Lourdes (“Heavy Trucks”). They were veterans of Paris’s pulp trade: the cheaply produced and poorly printed paperback novels called feuilletons. Souvestre was impressed by the young Allain’s ability, especially after seeing Allain churn out a seventeen-page article in two hours about a truck he had never seen before. They had no artistic pretensions and were in it entirely to earn their living. The characters are flat, the plots beyond hackneyed, and the dialogue overblown and bombastic. Allain and Souvestre ripped off other novels by the cartload and plagiarized their own works. They came up with the plot one week, wrote the prose over the following week, each one writing an alternate chapter, and then spent a week grooming the manuscript into a cohesive whole. Meanwhile, the marketing department arranged the cover artwork. An assignment handled by the Italian artist Gino Starace, whose lurid covers provided the perfect graphic milieu for the narrative. These presage the grisly aspects of EC comics and artists such as Johnny Craig and Bernie Krigstein.

It was three o’clock when Juve arrived at the rue Lévert, and he found the concierge of number 147 just finishing her coffee.

Amazed at the results achieved by the detective, the details of which she had learned from sensational articles in the daily papers, Mme. Doulenques had conceived a most respectable admiration for the detective of the Criminal Investigation Department.

“That man,” she constantly declared to Mme. Aurore, “hasn’t got eyes in his head, but telescopes, magnifying glasses! He sees everything in a second—even when it isn’t there!”

But why did Fantômas capture the imagination so strongly? The novels are not whodunits, nor even whydunits (as is the work of George Simenon), but howdunits. We know who did it: Fantômas. We know why: Lord of Terror, etc. But it’s the how that hooks us.

How did he get into the Marquise de Langrune’s bedroom after the door was locked?

How did he escape the Paris hotel after the Princess Sonia notified the authorities?

How did he trick Inspector Juve even when the detective practically walked him to the steps of the guillotine?

A recapitulation of the plot is irrelevant. A series of unsolvable crimes are committed. The detective Juve believes they are the work of Fantômas. In his pursuit of the villain he is assisted by Jérôme Fandor, a young man wrongfully accused of one of these crimes. The pair adopt various disguises and track Fantômas, who is also disguised, through the Paris underworld. There are set-piece scenes consisting of deathtraps, criminal locales, and a number of courtroom episodes. Severed heads and hands abound, as do bells dripping blood and disasters such as trainwrecks and shipwrecks. Colorful characters appear for a chapter and then disappear into the background. Identities are mutable, and in any given chapter one or more characters might remove their mask and reveal themselves to be Juve, Fantômas, or Fandor (or, after the eighth novel, Hélène, Fantômas’ opium-smoking, pistol-toting, cross-dressing daughter). This gimmick gets played so often that it goes well beyond the plausible, bypassing absurdity, verging on the pathological. The characters have no identity, and it’s only by wearing masks that they become real.

In this fact one can possibly see why the series appealed to the surrealists. Not only was the plot propelled by the actions of a nihilistic antihero at war with society, but the characters were only “real” when they pretended to be someone else. The results when attached to breakneck plotting and violent imagery approached a sort of pulp delirium that directly affected the imagination.

Fandor saw that Juve was staggering and seemed about to faint. He rushed toward him.

“Good God!” he cried in tones of anguish.

“It isn’t Gurn who has just been put to death!” Juve panted brokenly. “This face has not gone white because it is painted! It is made up—like an actor. Oh, curse him! Fantômas has escaped! Fantômas has gotten away! He has had some innocent man executed in his stead! I tell you, Fantômas is alive!”

Pierre Souvestre died of Spanish Influenza in 1914. Allain was sent to the trenches of the First World War, but survived to pen eleven more Fantômas novels (he also wound up marrying Souvestre’s widow). In 1913, Fantômas made the leap to movies in a series of serials directed by the silent-film pioneer Louis Feuillade (best known for his later serials Judex and Les Vampires). A 20-episode American serial followed in 1920; and Fantômas movies, television shows, and radio serials were made well into the 1980s. Later films resembled James Bond-style capers and featured technological gadgets and hidden bases. They also gave Fantômas blue skin.

Around the world Fantômas spawned a variety of supervillains. Throughout the rest of his life, Allain continued to churn out Fantômas-style characters such as Tigris, Fatala, and Miss Teria. The 1960s saw various Italian, French, and Spanish publishers competing with ever-increasing doses of sadism to follow the Fantômas model. The character had sunk so deep into pop culture as to be largely invisible. European comic characters Diabolik, Kriminal, Killing, and Satanik can all trace their heritage back to Fantômas. Other characters, such as Dr. Mabuse and the Joker, owe a fair debt to the Genius of Evil and his love of “beautiful compulsive” violence. In a strange character reversal, Fantômas even went on to become a hero. When the Japanese anime Ogon Bator was syndicated in Brazil the character was renamed Fantômas and protected the earth from alien invaders.

If all this sounds fun, you’re in luck. Tracking down Fantômas novels is fairly easy. The first novel is readily available as a Penguin Classic, and a variety of small presses and print-on-demand publishers produce translated reprints of some of the series in varying quality. There’s also an apocryphal storyline where Fantômas goes to England and fights Sherlock Holmes.

But, what is most intriguing in the Fantômas-myth is the notion that popular fiction can be intoxicating and serve as a catalyst to the imagination. It suggests the possible inspiration residing within soap operas, comic books, and mass-market paperbacks. By their very ubiquity and devotion to the trends of the present these items overcome our judgments and speak to our unconscious.

I believe there’s a charm in the violent popular melodrama of earlier eras. Whether it’s The Monk, Vathek, The Werewolf of Paris, or Flowers in the Attic. This stuff is shocking in wholly unsuspecting ways, and Fantômas is no different. Even all this won’t prepare you for how unstintingly absurd it all is. It needs to be experienced first hand.

* (This essay first appeared in April 2009 on the soon to be shuttered Internet Review of Science Fiction website. It’s been and edited and tidied up some for reprinting here.)

Justin, this is weirdly compelling. I’m going to pick up a Fantômas novel.

Let me know what you think.