By William A. Booth

“Heaven is just up there; one can see it and dream about it. Up there are the fruits of the Mexican Revolution, the heroes of the fatherland, the nationalized nation, the ejidos of the agrarian reform, popular culture, the expropriation of foreign oil companies, social security, rescued indigenous traditions, the murals of Diego Rivera.”[1]

– Roger Bartra, ‘Missing Democracy’

Earlier this year, I was fascinated to read a post here by Erin Zavitz entitled “The 2015-16 Haitian Elections: Politicizing Dessalines and the Memory of the Haitian Revolution”. Zavitz described the way Dessalines had been erased from official national ideology, only to be re-appropriated by popular demand. This century-long process brought to mind a similar series of developments in my own country of specialization, Mexico. Both the independence struggle (c. 1810-c1821) and the Mexican Revolution (1910 onwards, with little consensus on when it ended) brought forth their own galleries of heroes, sanitized, and remoulded to fit the purposes of their political successors. As Bartra notes above, this national-revolutionary pantheon is only a part of the superstructure which kept the post-revolutionary regime in power for seven decades, yet it is a crucial one.

The first time I was in Mexico for the independence day celebrations – in 2001, a few days after the 9/11 attacks, in fact – some friends took me to hear the local mayor read the grito. The grito is one of the most clearly defined expressions of the pantheon, a list of heroes wished long life before climaxing in three cries of ¡Viva Mexico! The modern version is not quite as stirring as the purported original Grito de Dolores made by Father Hidalgo in 1810 – the original, popular expression of anti-imperialist insurrectionary sentiment.

The grito, delivered each September 15th, is not technically an official independence day, but rather is a rebranding of the birthday of pre-revolutionary dictator, Porfirio Díaz. Independence was actually declared on 28th September 1821, eleven years later, but the manner in which Mexico achieved independence and the form of the new state doesn’t sit easily with the official national narrative.* Having disavowed the popular, multi-ethnic uprising of Fathers Hidalgo and Morelos, the creole elite eventually rallied around Agustín de Iturbide, a high-ranking royalist officer who turned his coat to lead the final charge towards independence. Having done so, he declared himself emperor, and consigned himself to infamy.

On 15th September 2001, I was staying in Tlalpan, and we walked down to the square to hear the grito. After the first few names, the mayor shouted ¡Viva Villa!’ to some consternation. The revolutionary general, Pancho Villa’s standing as a hero is ambiguous at best, and his legacy is pretty hard to sanitize. This was my first inkling that the pantheon had a set of unspoken criteria for entry: dead Mexicans, who had popular ideas or undertook momentous acts, which could be repackaged for consumption across classes. Villa is still too much of a bandit for some to stomach.

The Mexican Ambassador to the UK, Diego Gomez-Pickering, slipped up with the grito in 2015. Standing on the balcony of the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, he rattled through the list, left off two ‘canonical’ names and included Porfirio Díaz and the peasant revolutionary leader Emiliano Zapata. As many commented at the time, the inclusion of leaders from long after the independence era was unorthodox, though it is hardly unknown – I’ve heard Zapata included on many occasions, but Porfirio Díaz in particular was seen as a step too far. People wondered why he hadn’t also included Augustin de Iturbide, or Maximilian I, the unfortunate Hapsburg transplanted from Austria to the Mexican throne on behalf of Napoleon III. And this reveals the basic function of the pantheon: as a progressive, popular cloak, worn to conceal the essentially authoritarian body politic. For instance, the hero of oil nationalization (1938), Lázaro Cárdenas, enacted policies which ran counter to almost everything Mexican governments have done since the war, yet he has been consistently lauded and revered.

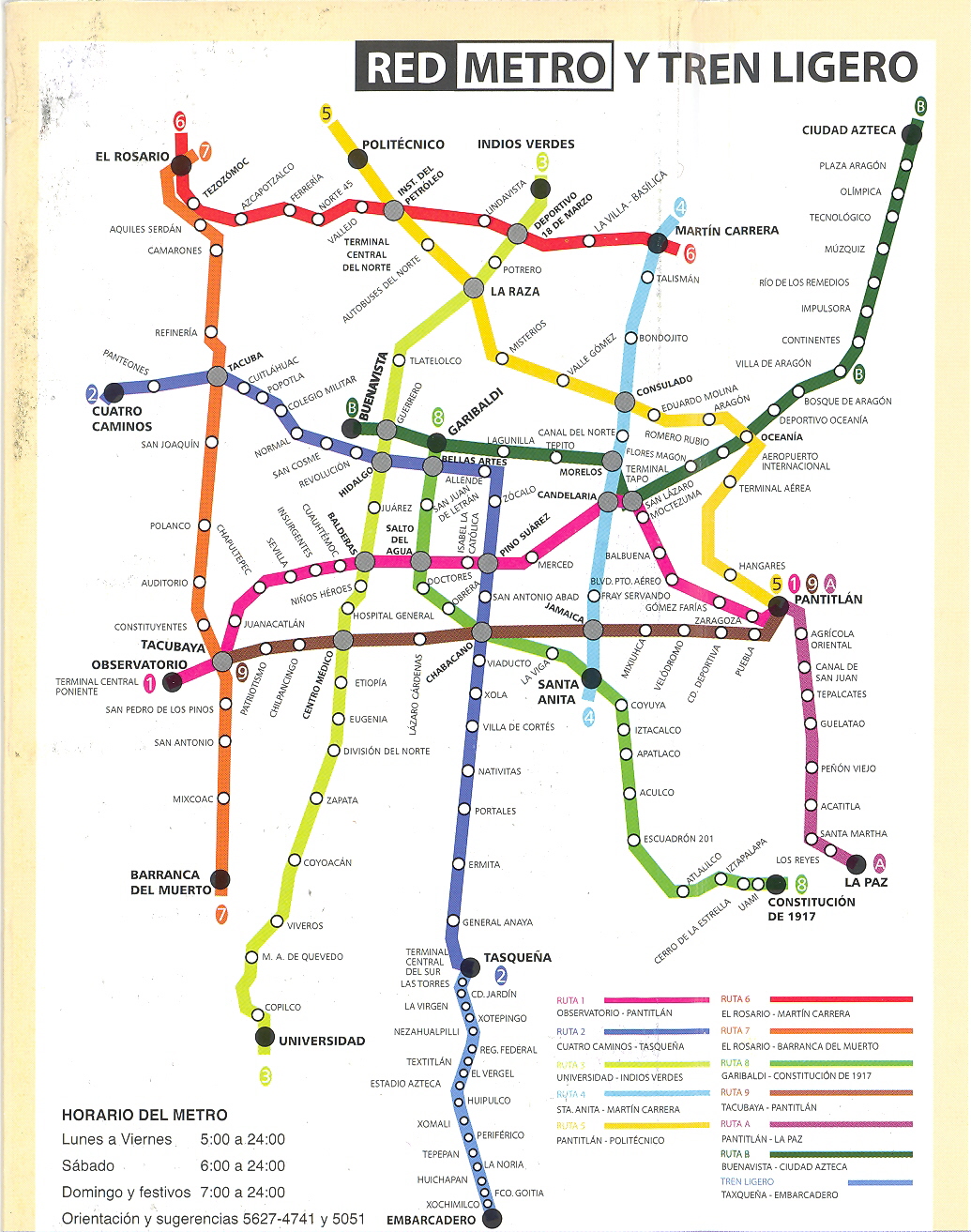

The pantheon goes far beyond the grito, encompassing heroes of the Reform Wars and liberation from French occupation, and later of the Revolution. It can also reach back, linking modern rule to that of the pre-Hispanic Tlatoque, or emperors. We can find the faces and names of the chosen ones in murals, on the metro map, in the names of streets and public institutions, and of course, in monuments such as that to Cuauhtémoc in Mexico City. Mexico’s post-coloniality is represented in a myriad of ways.

Zapata, unquestionably a national hero now, was killed in 1919 by the (briefly) victorious Carranza regime. Later, successive post-revolutionary governments used his image to “legitimize” their agrarian policy. Sanitizing Zapata was dangerous though, and in 1994 a rural, largely indigenous group seized part of the Chiapas state in his name. Such risky political absorptions continue. In 1999, a Metro B station in Mexico City was named after the anarchist Ricardo Flores Magon, an anti-authoritarian hailed as a national hero by both government and dissidents for many decades. Perhaps, like Dessalines, sufficient time had passed for his image to safely adorn a piece of infrastructure, yet elsewhere, in places like Oaxaca, Flores Magon’s name and legacy are invoked in current struggles against the Mexican regime. How long until a Metro station is cynically named for Subcomandante Marcos — who some call Mexico’s Che Guevera?

Alan Knight has argued that “images and allegiances drawn from a (partly mythic) past helped shape discourse, policy, and political affiliation, and did so across a wide ideological spectrum… radicals like Adelberto Tejeda were at pains to place themselves within old historical traditions: in this case, the liberal tradition of Lerdo, Juarez, and Ocampo.”[2] By creating one lineage running from the Aztec Triple Alliance to independence, through the Liberal period and on to the Revolution, the pantheon has absorbed a great swathe of ideological and ethnic identities. Octavio Paz talks of “distinct and contradictory phases of one continuing effort to break free”, and the PRI (the party which ruled, essentially, from 1929-2000) placed themselves as the logical culmination of that effort.[3]

Another, more concrete, expression of the pantheon is the Rotunda of Illustrious Persons, a special section of Mexico’s largest cemetery. Here you can find the graves of many of those mentioned previously, as well as a host of others including oft-imprisoned painter and communist (and would-be assassin of Trotsky) David Alfaro Siqueiros, painter María Izquierdo, union leader Vicente Lombardo Toledano, and composer Silvestre Revueltas. Their many talents and ideologies are brought under the national umbrella and placed at a safe historical distance.

The diversity of the pantheon gives it tremendous flexibility as a political tool. Its members range from firebrand revolutionary priests like Hidalgo and Morelos to lofty men-of-letters such as lawyer Pino Suárez. While few women have been elevated into the group (a notable exception was Josefa Ortiz de Domínguez, a supporter of the Mexican War for Independence), a number of Mexicans of indigenous heritage are there, though whether they are representing a multiethnic nation or being used to hide its gross inequalities is another matter.** Mexican rulers have benefitted greatly from having a large and silent supporting cast drawn from so many backgrounds. The result, as Knight suggests, is that “despite its hoary and ponderous image, tradition proved remarkably nimble.”[4]

Dr. William A. Booth is a teaching fellow at University College London. He specializes in in Mexico, Latin America, and twentieth-century Socialism and Communism. You can contact him at williambooth@gmail.com or on Twitter @WilliamABooth.

Title image: Grito delivered at Dolores Hidalgo. From left to right: Guadelope Victoria, Miguel Hidalgo, Josefa Ortiz de Dominguez, Jose Maria Morelos

*Actually there is a third contender, that being 13th September, when (in 1813) the Congress of Chilpancingo declared independence. This date has another patriotic connotation though: it is dedicated to the memory of the Niños Heroes (Boy Heroes), six young cadets who gave their lives rather than surrender Chapultepec Castle to the advancing U.S. army in 1847, but that’s another story…

**Two prominent Afro-Mexicans, José María Morelos and Vicente Guerrero, are rarely referred to as such.

[1] In Bartra, Blood, Ink and Miseries and Splendors of the Post-Mexican Condition (Durham, NC : Duke University Press, 2002), 65.

[2] Knight, “Popular Culture and the Revolutionary State in Mexico, 1910-1940,” Hispanic American Historical Review, 74: 3 (1994), 398.

[3] Octavio Paz, The Labyrinth of Solitude (New York: Grove Press, 1985), 167.

[4]Knight, 398.

Further reading:

Eric Zolov (ed.), Iconic Mexico: An Encyclopedia from Acapulco to Zocalo (ABC-CLIO, 2015)

Paul Gillingham, Cuauhtemoc’s Bones: Forging National Identity in Modern Mexico (University of New Mexico Press, 2011)

Samuel Brunk & Ben Fallaw, Heroes and Hero Cults in Latin America (University of Texas Press, 2007)

Thomas Benjamin, La Revolución: Mexico’s Great Revolution as Memory, Myth and History (University of Texas Press, 2000)

It is a very interesting post. One point: Independence was declared by the Congress of Chilpancingo on November 6, 1813, not September 13. See http://www.pim.unam.mx/catalogos/hyd/HYDV/HYDV091.pdf and Alfredo Ávila and Erika Pani, “De la representación al grito, del grito al acta. Nueva España, 1808-1821”, in Las declaraciones de independencia. Los textos fundamentales de las independencias americanas, ed. by Ávila, Dym and Pani (Mexico City, El Colegio de México, 2013), pp. 275-295.

LikeLike