As much as I love overpriced gizmos in my living room, I still tend to be reluctant about new standards. TVs are a great example. I've appreciated the bonuses offered by 3D, 4K, and HDR, but I concede they all lack content and are less amazing than salespeople would lead you to believe. They're also generally not worth replacing TVs that are only a few years old.

The same goes for audio, which fortunately hasn't strayed far from a "5.1" surround-sound profile since the dawn of DVD adoption. Really, I've been fine with two good speakers and a subwoofer for my entire adult life. I laugh at overblown, pre-film Dolby intros in a theater. I shrug at the surround effects in hectic action movies. I have failed A/B tests in picking out major differences between 5.1 and 7.1 systems.

Surround audio can be cool, sure. But if I were to ever change up my entire living room, I'd need something to blow my aural expectations away. This week, that might have finally happened.

I am not lying when I say that a "spatial audio" experience this week left me gasping, laughing, and crying in sonic bewilderment. The impact came in a way that I never expected: not from a monstrous demo of sci-fi blasts in a film or video game, but from the acoustic majesty of an R.E.M. album brought to life anew. What's more, the engineers behind this "first-ever" Atmos release were happy to share how they pulled it off—and how the Beatles' Sgt. Pepper set everything into motion.

Sweetness follows

-

R.E.M. poses on a beach in Miami in 1992, near one of the recording studios used for Automatic For The People.Anton Corbijn

-

Michael Stipe crowdsurfs during the video shoot for the single "Drive."Anton Corbijn

-

The '90s, man. The '90s.Anton Corbijn

-

Where's Michael? THERE's Michael!Anton Corbijn

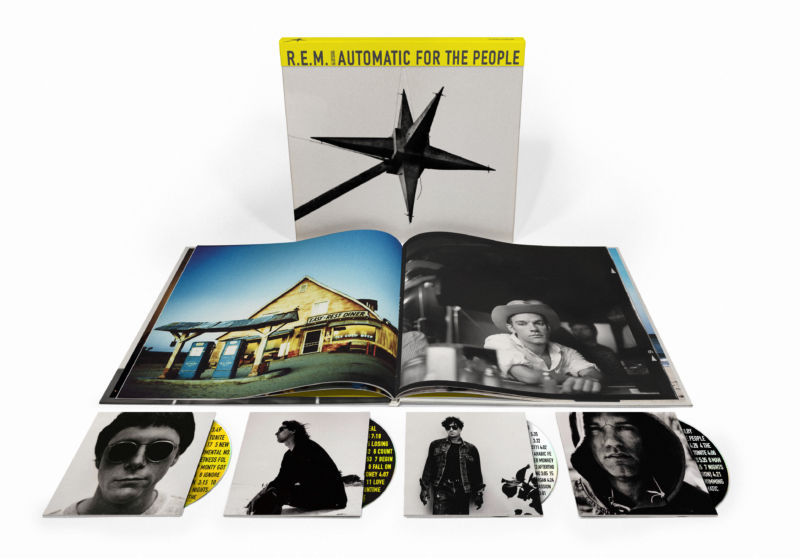

Roughly a month ago, the PR team working for the Athens, Georgia, pop/rock band R.E.M. sent me an out-of-nowhere invite to listen to the band's latest 25th-anniversary re-release: the 1992 album Automatic For The People. R.E.M. began packaging and selling special editions of albums well before the band split in 2011. As a lifelong fan, I've picked up each one, full of unearthed B-sides and demos. I didn't have much access to counterculture art as a kid, but I savored whatever mainstream gateway stuff I could get my hands on. R.E.M. showed up in my pre-teen life as a soft-and-weird complement to the loud-and-weird stuff I loved in metal and grunge. Automatic For The People was equal parts acoustic and electric, not to mention both wholesome and subversive, and that changed me as an 11-year-old.

As much as I love Automatic, I had no Ars-specific reason to request a promotional copy. But my tech-critic attention was captured by one sentence: this would be the "first major commercial music release in Dolby Atmos." From the announcement:

This technology delivers a leap forward from surround sound with expansive, flowing audio that immerses the listener far beyond what stereo can offer. It transports the listener inside the recording studio with multi-dimensional audio—evoking a time when listening to music was an active, transformative experience and reigniting the emotion you felt when you first heard the album in 1992. R.E.M.’s Automatic For The People is the first album to be commercially released in this expressive, breathtaking format.

I'd normally dismiss such a buzzword-filled promise. Worse, its attachment to the Dolby Atmos standard left me a little cold. Atmos is one of the latest entries in the burgeoning "spatial audio" landscape, right next to DTS-X and Windows Sonic. The sales pitch: if you plug headphones into the right hardware and listen to compatible content, sounds will be processed in such a way that their frequencies trick your brain. Sound effects and music will light up "around" you in a virtual-surround way. Unlike older virtual-surround trickery, this stuff should sound like a full, three-dimensional dome of sound, so that you can perceive the angle and height of sound. (Normal surround-sound systems operate with a flatter circle of sound.)

Outside of headphones, a more convincing "sound-bouncing" system can be used with a combination of a compatible receiver and specially calibrated speakers pointed at an angle, either directly at listeners or angled off a flat ceiling. The effect is supposed to be the same: you hear sounds all around you in a full dome, with each element tuned for different locations and heights in a room, as opposed to a flat circle.

But I'd been confused by products and demos in the past. One huge problem: many "virtual surround" headsets work by requiring third-party hardware or software, which translates anything from a 7.1 signal to a stereo signal into its own approximation of virtual surround. This stuff sounds goofy at best and weird at worst, especially if any headsets' frequency tricks add "swishing" effects to a booming soundscape. In addition, even at the most high-end, perfectly calibrated theaters, I tend to feel unmoved by surround-sound systems. They try to attach audio perspective to sound effects in relation to whatever appears on the screen, but visual cuts and edits make it impossible to feel like I'm hearing truly accurate all-around sound.

I was reluctant about the technology and the promise, but I was also giddy about R.E.M. of all bands possibly reinvigorating it. I caved and quickly requested a review copy.

reader comments

273