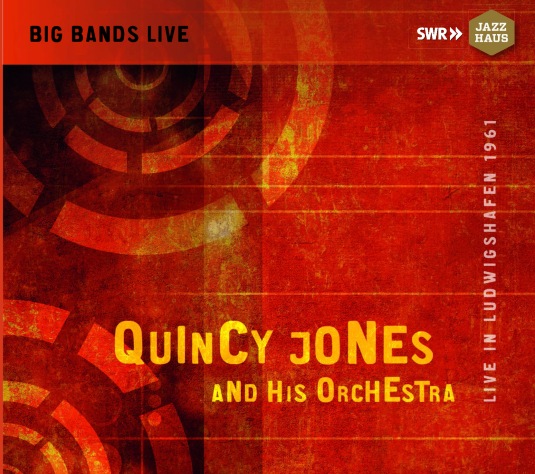

QUINCY JONES AND HIS ORCHESTRA LIVE IN LUDWIGSHAFEN 1961 / Air Mail Special (Christian-Goodman-Hampton); G’Wan Train (Quincy Jones); Solitude (Ellington-Mills); Stolen Moments (Oliver Nelson); Lester Leaps In (Lester Young); Moanin’ (Bobby Timmons-Jon Hendricks); Summertime (George Gershwin-DuBose Heyward); I Remember Clifford (Benny Golson); Ghana (Ernie Wilkins); Banja Luka (Phil Woods); Caravan (Juan Tizol-Duke Ellington-Irving Mills); The Midnight Sun Will Never Set (Quincy Jones-Dorcas Cochran-Henri Salvador); Quincy Jones introduces the orchestra; The Birth of a Band (Quincy Jones) / Benny Bailey, Paul Cohen, Freddie Hubbard, Sixten Eriksson, tp; Julius Watkins, Fr-hn; David Baker, Curtis Fuller, Åke Persson, tb; Phil Woods, a-sax; Budd Johnson, t-sax; Joe Lopes, Eric Dixon, t-sax/fl; Sahib Shihab, a-sax/bar-sax; Les Spann, gt/fl; Patricia Bohn, pn; George “Bumblebee” Catlett, bass; Stu Martin, dm; Carlos “Patato” Valdes, congas / SWR Jazzhaus JAH-455 (mono, live: March 15, 1961)

Most people out there who know Quincy Jines’ name know him solely from his Hollywood work, which has occupied him since the early 1960s. Those who remember him as a real jazz musician are few, and generally hardcore fans. Some may recall that he got his start as an arranger for the stellar Lionel Hampton band with Clifford Brown in the trumpet section that toured France in 1953; others may know him from his 1956 album, This is How I Feel About Jazz (Impulse), but only a hardy few remember this 1961 big band which, with changes in personnel, played not only this great date in Ludwigshafen, Germany but also made a couple of studio albums and a live LP from Newport on July 3, 1961. The personnel, however, shifted after this European tour, as Jones found it impossible to continue to afford such big-name stars in each section. This particular concert has never been issued before in any format.

Ironically, the lineup given by SWR Jazzhaus is slightly wrong. They claim that Melba Liston is on trombone, but she is not; the third trombonist, after Curtis Fuller and Åke Persson, is David Taylor. Les Spann is credited as playing guitar only, but he also doubles on flute. When Jones introduces the band on track 13 there are several names mentioned that aren’t even noted, such as trumpeters Paul Cohen and Sixten Eriksson, French hornist Julius Watkins, saxists Budd Johnson and Joe Lopes, pianist Patricia Bohn and bassist George Catlett. But the total effect of this lineup on the music is absolutely galvanizing. Much has been made of Jones’ arranging skills, and he was indeed a quick worker who could turn out well-crafted scores at a moment’s notice (after his move to Hollywood, one of his projects was writing several arrangements quickly for the Count Basie band to play behind Frank Sinatra on the Hollywood Palace TV show), but in terms of voicing and texture he was fairly conventional. Aside from occasionally using a flute here or French horn there for color, his aesthetic was based on Count Basie’s “atomic band” of the 1950s. This doesn’t mean it was bad, only that it wasn’t terribly original.

But the joys of listening to this orchestra are not necessarily in the charts, good though they are, but in the scintillating solos taken by all concerned. There is scarcely a moment in this breathtaking concert that will not have you on the edge of your seat as Jones’ all-star lineup continually prod each other to extraordinary heights and build on each others’ solos. The old Charlie Christian-Benny Goodman classic Air Mail Special is taken at an atomic-age tempo, and so is George Gershwin’s Summertime, normally a ballad. Among the standout soloists here are trumpeters Freddie Hubbard (the busier solos) and Benny Bailey (the more sparse ones), hornist Watkins, trombonists Baker and Fuller, and saxists Woods, Johnson, Dixon and Shihab. This was probably the last band in which Sahib Shihab played before he struck out on his own and moved to Scandinavia, where he led a superb band of Danish musicians for several years (collectors also know him from his early work with Thelonious Monk and, just before joining Quincy, clarinetist Tony Scott). The entire band is truly on fire here, sounding both energized and relaxed at the same time, and the results are simply spectacular.

It’s interesting to hear full-band arrangements of some of these pieces that are normally known to jazz buffs as small-group vehicles, such as I Remember Clifford, Moanin’ and Stolen Moments. One of the few failures here, arrangement-wise, is his chart of Lester Young’s Lester Leaps In. It’s brilliant and explosive, but to my mind this isn’t the kind of piece that works well in a full-steam-ahead big band chart with blasting trumpets. A more intimate arrangement would have worked much better, in my view. But this is a rare artistic lapse in a set that sizzles from start to finish. The sound quality is a little on the dull side, so if you just turn up your treble control on your amp when playing it you’ll get better sound out of it.

This is a heck of a CD and a good sound picture of exciting jazz in the era just before it all splintered into several different directions including free-form and funk.

— © 2016 Lynn René Bayley

Read my book: From Baroque to Bop and Beyond: An extended and detailed history of the intersection of classical music and jazz