Archive for June, 2014

New Sergei Isupov work added to the collection

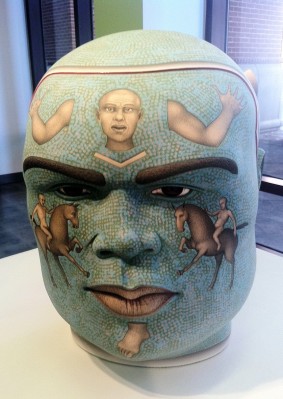

The ASU Art Museum is thrilled to add its first Sergei Isupov sculpture into the permanent ceramics collection thanks to David Charak, Ferrin Contemporary and the artist. Isupov’s piece, Firey, created from stoneware, stain and glaze, is a beautiful new addition to the collection. It was given to the museum from a series of Isupov’s large-scale heads and appeared at the NCECA 2009 conference at the Mesa Contemporary Arts.

Sergei Isupov, “Firey,” 2009. Stoneware, stain, glaze. 25 ¾ x 19 ½ x18 in. From the ASU Art Museum collection, gift of David Charak, Ferrin Contemporary and Sergei Isupov.

Russian-born artist Sergei Isupov is quite often called an erotic Surrealist for his bold depictions of sexuality, relationships and human encounters. He uses his own experiences as well as human observation to create a unique approach to the world of sculpture. “My work portrays characters placed in situations that are drawn from my imagination but based on my life experiences,” said Isupov. “My art works capture a composite of fleeting moments, hand gestures, eye movements that follow and reveal the sentiments expressed.”

Various narrative themes are conjoined together to create Isupov’s sculptural ceramic forms, inspired by particulars from his life. Personal interpretation is very much expected with his work.

Isupov states that, “Through the drawn images and sculpted forms, I capture faces, body types and use symbolic elements to compose, in the same way as you might create a collage. These ideas drift and migrate throughout my work without direct regard to specific individuals, chronology or geography…Through my work I get to report and explore human encounters, comment on the relationships between man and woman, and eventually their sexual union that leads to the final outcome — the passing on of DNA which is the ultimate collection — a combined set of genes and a new life, represented in the child.”

Sergei Isupov, “Firey,” 2009. Stoneware, stain, glaze. 25 ¾ x 19 ½ x18 in. From the ASU Art Museum collection, gift of David Charak, Ferrin Contemporary and Sergei Isupov.

Firey, alongside numerous other ceramic works from the ASU Art Museum’s collection, is on display now at the Ceramics Research Center at the Brickyard, located at 699 S. Mill Ave, Suite 108, Tempe, Ariz. 85281. If you haven’t seen our beautiful new space yet, you’re missing out! Plan your visit today, or call 480.727.8170 for directions and hours.

— by Nicole Lechner, ASU Art Museum intern

Artist Pablo Helguera talks language insiders, e-books and ‘Librería Donceles’

This spring, the ASU Art Museum presented two concurrent solo exhibitions of work by artist Pablo Helguera. Pablo Helguera: Librería Donceles and Pablo Helguera: Chrestomathy, are the first presentations outside of the East Coast of this new work by Helguera, a world-renowned visual and performance artist whose work weaves together personal and historical narratives in the context of socially engaged art and language.

Librería Donceles is an itinerant, functional Spanish-language bookstore of 12,000 used books in Spanish on every subject—including literature, poetry, art, history, biology, medicine, anthropology and politics, as well as children’s books. To create the installation, Helguera assembled donations of books from individuals and groups in Mexico City and elsewhere, offering prints of his previous artworks in exchange for boxes of books. Librería Donceles is currently on view through June 28, 2014 in downtown Phoenix at Combine Studios Gallery, home of the ASU Art Museum International Artist Residency Program.

During one of Helguera’s recent visits to Phoenix, he sat down with Julio César Morales, ASU Art Museum Curator, and Brittany Corrales, Windgate Curatorial Assistant and master’s candidate in art history, to talk about socially engaged practice, e-books, and the “Bob Dylan of Mexico.”

JCM: Librería Donceles is a project that was born in New York City in 2013 and influenced by the fact that there are 2 million Spanish-speaking people in New York and not one Spanish-language bookstore. Here in Arizona, where English is the official language and it is against the law to teach ethnic studies in K-12 public schools, how do you see the bookstore functioning in regards to the current social environment in Phoenix?

PH: It was very important to me to be able to bring Librería Donceles to Phoenix as I see it as a way to promote knowledge of the culture around Spanish language — something that I believe is necessary if there is going to be a discussion on banning books. The project seeks to show that every language has a great depth and richness that reaches all disciplines and goes back centuries. I wanted to show that regardless of what language they are written in, knowledge is universal and contributes to the betterment of individuals and communities all over the world. I also believe that prejudice emerges from distance — it is common to judge something without seeing it with your own eyes. So we have thousands of books there now, for people to meet in person, and whether one speaks Spanish or not, I think it may be surprising for someone to walk in there and ponder on the value and importance of the book.

BC: To create Librería Donceles, you assembled donations of books from individuals and groups in Mexico City and elsewhere, offering your artwork in exchange for books and producing an Ex Libris for each donor that acknowledges the provenance of every volume. What sort of ephemera did you discover in the pages of the donated books?

PH: There were a myriad of things in them: movie tickets, subway tickets, laundry lists, religious pamphlets, love messages, cryptic messages, photos, business cards. It was amazing what we found. I particularly liked a hotel towel receipt – ones that you would use to borrow towels in the pool in places like Acapulco. They all spoke of the personal circumstances under which the book was being read.

JCM: Can you talk about the origins of socially-engaged art practice? Some may consider it a catch-all for what cannot be defined within a specific art genre. However, as a pioneer or leader within this field, can you forecast a future of how this genre might be able to push the boundaries within the traditional notions and relationships between audiences, artists and cultural spaces?

PH: You could say that art in the public realm has always existed, even before it was a commodity or it was housed in museums. Art comes from the public, from vernacular expression, and within the modernist tradition, the effort to bring art into the public realm was sort of a political gesture- ranging from the Mexican muralists until today. The practices that started emerging over the last decade ago or so was, in my view, an attempt to connect with that political spirit of social investment by furthering what process-based art had done in the previous decades, and using elements from relational aesthetics and institutional critique but trying to move on from the museum discourse. I am afraid that socially engaged art is quickly becoming an academic discipline and we may be creating already a “genre” out of it. But I believe that is, in essence, an inevitable part of the assimilative process of every new set of practices. What I don’t think is going to go away is the desire to make art matter again in the public discourse. So my hopes is that socially engaged art today, as we understand and define it right now, will evolve into new forms of art making that operate independently from the existing market structures of art.

BC: You currently work as the Director of Adult and Academic Programs at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. How has your experience in education and programming informed your art practice, or vice versa?

PH: I have done museum education on par with my artistic practice since 1991 and as a result my experiences as educator have influenced my work as artist and vice versa. It is mainly the reason why I started making work that dealt with the social context of art—because that is what you deal with as an educator— and that is why as educator I am interested in supporting forms of learning that are placed at the center of the artistic process.

JCM: In recent years, pedagogy has played an important role within the curatorial practice in major projects such as Documenta and the Mercosul Biennale in Brazil. Is it possible that we can “learn” to understand art and life in a more “speculative” understanding between the relationship of practice and exchange?

PH: Many of us believe that all this relatively sudden interest in pedagogy by the contemporary art world is nothing other than the recognition that what many artists wanted to do with their work has to do more with education than with art appreciation. We don’t want works that are there merely to be admired: we want to make works that truly matter, that truly can be transformative. And it is education theory that shows you how transformative experiences are created, ranging from John Dewey to Jerome Bruner to Paulo Freire. The problem is that pedagogy tends to continue to be perceived as didacticism, not as experiential practice.

BC: As a bibliophile, what do you believe is the role of printed books as objects in our increasingly paper-less, virtual world?

PH: There are evident and not-so evident contrasts between the physical object of the book and the e-book. But amongst the not most evident ones, there’s the issue of personal ownership. You don’t own the e-books in your library- you mainly rent them. At a first glance this may appear to seem democratic, but it is not. A corporation owns all these books, all this content basically, and gives you access to them for a fee. This has an impact on how knowledge is produced and transmitted. You can’t give away or share your library to others, you can’t lend books. So what is being lost is the personal communication and production of knowledge and experiences that lead to knowledge through the object of the book.

JCM: I have always thought of Oscar Chavez (Mexican folk singer and cultural activist) as the “Bob Dylan of Mexico.” Can you talk about the influence of his craft within your artistic practice? (I will not mention to anyone that he is your uncle).

PH: I grew up in a family of artists- some of them were classical musicians, others, like Oscar, were involved with popular traditions. In my grandmother’s house, on Sundays, we would gather and both kinds of art coexisted — we would start dinner listening to Caruso, but after dinner —and a few drinks— my aunts and uncles would sing rancheras. As a teenager I would go with my aunts to Oscar’s concerts at the Auditorio Nacional (where he still performs every year). In the 70s and 80s, during the hard years and later decay of the PRI, it was difficult to exist as a true voice of dissent. Yet Oscar never flinched and was implacable in his scathing criticism of the government—so those concerts at the Auditorio Nacional felt like true demonstrations. I always admired Oscar’s ability for satire, his integrity and the way he managed to touch the public. These days I am thinking a lot about how important is to think of that legacy for us as artists.

Helguera and curator Julio Cesar Morales enjoy a musical moment in Librería Donceles. Image by Tim Trumble.

BC: If language creates meaning, are there certain linguistic borders that are not traversable? Can you provide an example of a particular word or phrase whose nuances you find difficult to translate from Spanish to English?

PH: There are absolutely lots of linguistic borders. The easiest to identify is localism and humor. When you learn a language (and even when you are a native speaker) the most challenging thing to understand are local and internal dialects, which may make reference to things and topics that you may not be familiar with. In 1960, a Mexican writer named Armando Jiménez published a book that became an instant classic, Picardía Mexicana, which was an incredible compilation of Mexican jokes, off-color phrases and general nastiness of the language. A book like that shows you how elaborate and intricate humor can become, and how it evolves so quickly in time and place. The Mexican humor of 1960 is totally different to the one in 1970 or 1990 or today. Some jokes survive or become transformed, but it all responds to the immediate social context. Finally, there is a big difference between understanding a joke and finding it funny. You can intellectually understand why something that is said may be considered funny by some people, but when you actually laugh without analyzing it, that means that you are an insider of that language.