It’s unusual to be able to glimpse into the creative process of a director – so much of what they produce is fleeting if a theatre director, and subject to reinterpretation if a film director. It is also fair to say that many, if not most directors, fail to keep records of their work, and throw away hastily written notes once a production is finished. The archive of Stanley Kubrick is therefore something of a rarity – a full, detailed record of his work on all his movies, and his research for projects he never managed to make. When Kubrick died in 1999 his personal archive passed to what is now UAL, who have provided most of the materials for this major retrospective, being held at the Design Museum in Holland Park.

‘Archives’ usually suggests box upon box of boring paperwork, but that is absolutely not the case here. There is every sort of document you could imagine from the industry of film-making. There is correspondence to and from Kubrick on a range of subjects, from the need for specialist consultants in 2001: A Space Odyssey, to replies from distribution agents regarding certification issues. There are props, set elements and set models from 2001, Dr Strangelove and others. There are costumes from Spartacus and from the movie Barry Lyndon, perhaps one of Kubrick’s less well-known films. There are: production stills from every movie he ever made; screenplays for most of them, annotated by Kubrick himself; a selection of clapper boards; two full-size film cameras; a variety of lens for a range of shooting scenarios; Kubrick’s hand held camera – capable of shooting a minute’s worth of footage at a time; the shooting schedules for several projects; an editing table, and even an actual Oscar. And that’s just a sample – in all there are around 700 objects, all of them offering a fascinating insight into Kubrick’s work.

-

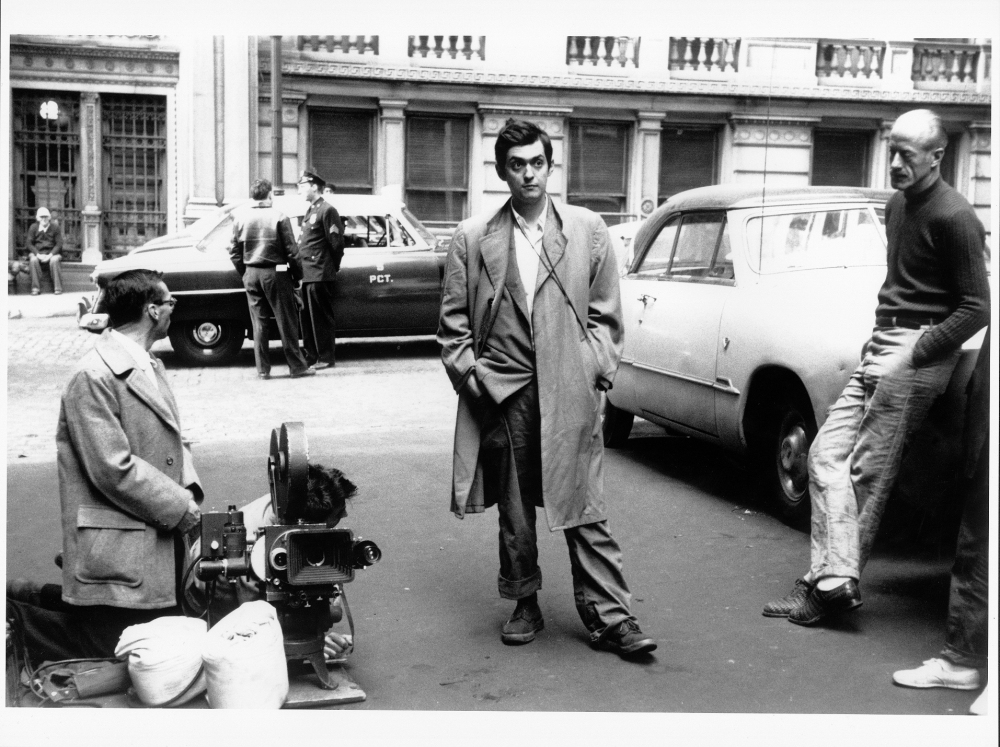

Credit: Stanley Kubrick during the filming of Killer’s Kiss (The Tiger of New York, USA 1955). © Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer.

After entering the exhibition space by walking over a reproduction of a carpet from The Shining, you pass through a space playing excerpts from Kubrick’s movies in ‘one-point perspective’. The first substantial space introduces you to the art of film-making, as practised by Kubrick. Covered here is everything from his early notes on adaptations of various books, a model of the centrifuge used in 2001, with detailed descriptions of how the real set was constructed and the challenges of that process, and ephemera from his movies, including clapper boards and posters.

It’s here also that you encounter the first substantive display – an area dedicated to the film Napoleon; a film Kubrick never got to make. Included in the diorama are; a selection of the books Kubrick had read as research; a huge sheet with the scenes intended to be shot listed with their location and cast requirements; Kubrick’s annotated biography of Napoleon, with his typed notes, carefully arranged on index cards, with a colour coding system recorded for reference, as well as an entire mini-cabinet with index-card notes. These items, in fact the whole exhibition, illustrates Kubrick’s meticulous care in researching any project he wanted to be involved with – and perhaps begins to explain why Kubrick’s movies took so long to make.

Kubrick’s film-making techniques are astounding – and they’re theatrical. Amongst the annotated screenplays, not just for Napoleon, but for those movies he was able to make, are notes that would be familiar to a theatre director – Kubrick is asking questions of how the characters feel at any given moment, how they should interpret their lines of dialogue, even what their motivation should be. This seems highly unusual to see from a film director – we’re often led to believe that film-making is wholly about getting the right shot, about filming in tiny fragments, and securing close-ups. To see that Kubrick was thinking about performances as well, an area not often discussed, is fascinating, and perhaps suggests why he remained unhampered by the restrictions of genre, and delivered movies which still resonate with audiences, some twenty years after his death, and in some cases, fifty years or more after they were made.

Kubrick was a classical film-maker – the insightful commentary provided within the exhibition notes that he often drafted his own screenplays, provided commentary on those written by others, knew what shots he wanted and understood how they needed to be obtained – he even undertook his own editing. He understood all of the roles within a movie, having started off undertaking all of the work in his first films, made in New York. He had an aesthetic vision for each film – and consulted with set and costume designers, whose work is that celebrated in the latter half of this exhibition, to bring that vision to reality. After the first space, in which Kubrick is celebrated, we shift into a series of spaces, one for each of his major movies, in which the design elements are those which are celebrated.

It’s here that you can see again and again the care and attention to detail involved in making movies – and gain an understanding of the ‘smoke and mirrors’ nature of the industry. There’s significant attention given to the recreation of the ruined Vietnamese city of Hue in the former Beckton Gas and Coke works – this then derelict industrial site was used to hosting TV and Film companies – it had been used in a Bond movie some six years before Kubrick’s designer for Full Metal Jacket, Anton Furst, turned up with a demolition ball, and a lot of strategically placed dynamite, and turned the eastern edge of London’s then abandoned docklands into war-era Vietnam. This transformation of a part of London is typical of Kubrick’s film-making process – he rarely wanted to travel far to make his movies, and so sent his designers and their scouts to find and convert locations that could convincingly replicate Manhattan, the Rocky Mountains or even Eighteenth Century Prussia.

The two elements of this exhibition: Kubrick and Design, are interwoven throughout the exhibition – showing that one could not have been as effective as it was without the other: Kubrick’s vision inspired the designers, whose work in turn inspired Kubrick. There’s also an air of involvement that seems to be absent from the contemporary movie business – there are several displays showing the evolution of poster designs or title graphics for some of Kubrick’s movies, notably A Clockwork Orange, with copies of correspondence between Kubrick and his designers, commenting on and finessing the ideas suggested – it’s almost inconceivable that a modern-day film director would be this involved with the minutiae of the marketing surrounding a film, and inconceivable that a marketing department wouldn’t now be involved from before a single frame of any modern movie had even been shot. But this entire exhibition is a remnant of a bygone era – things were different then.

One thing which was different, but perhaps less so than we would wish to think, is the large absence of women in Kubrick’s movies. There are few or no substantial roles for women in Full Metal Jacket or A Clockwork Orange, and in Spartacus Varinia could almost be replaced with ‘a sexy lamp’ and be as effective a motivation for Kurt Douglas’ eponymous hero. Even Eyes Wide Shut, infamously starring Tom Cruise and Nicole Kidman when they were a married couple, pays no more than lip service to its female characters, with the scantily clad silent women at the elite party acting as mere set decoration whilst the camera lingers on their nude bodies – the Bechdel Test is not being passed in Kubrick’s movies.

Controversy was a prominent and persistent feature of Kubrick’s work, from Lolita, a relatively early work in 1962, right through to the 1999 post-death release of Eyes Wide Shut. Whilst Kubrick may not have set out to stir controversy, he did know how to exploit it – the exhibition features numerous examples of correspondence between Kubrick and various individuals, who are writing to complain about the contents of his movies. The controversy around Lolita was so great that the poster deliberately referenced the furore, stating “How did they ever make a movie of Lolita?” and using images that sexualised the young star of the movie, Sue Lyon, who had been dressed and posed in a provocative manner that was never a part of the actual movie. Perhaps Kubrick deserves some kudos for making the movies he wanted to make, and refusing to be censored?

Again, in the contemporary era, any movie studio would have the power to reign in such controversial movies, scenes or storylines, and it is testament to Kubrick’s power as a director that he was able to shoot and edit these movies seemingly without interference from the studios or producers. But because Kubrick made movies for so long in which women were the subjects of violence, or sexualised to an extremely heightened degree, this treatment of women became engrained in culture, and it is only very recently, with the emergence of the #MeToo movement that this treatment of women as characters within entertainment has even begun to be questioned. Indeed, some of the troubling content of Kubrick’s movies is never particularly addressed – this exhibition is a celebration, not a forensic examination – but I do feel that some commentary about these issues may have helped the audience to begin to question the values embodied with these movies. These movies were, and remain, exceptional pieces of art, but as a contemporary audience we have the right and the obligation to point out where groups of people were marginalised, excluded or mistreated in art made in eras when the power of middle-class white men went (publicly) unchallenged.

It remains however that this is an exceptional exhibition of a career of an exceptional film-maker. In a clever conceit, the interior walls of the exhibition space have been made in the manner of film set ‘flats’, with wooden supports and cloth or wood board covering – there’s a very filmic air to the whole space, and the excerpts from the films themselves are on constant rotation in a series of generously sized sub-rooms. The whole exhibition feels generous – there’s a lot of items, displayed in a creative way, in a generously sized space which takes a long time to experience. I anticipate that examining every item, reading every display, and watching every excerpt from a film or behind the scenes interview would take almost three hours in total.

Kubrick was a master of film-making on an epic scale, which is reflected in this epic exhibition of the craft, technique and power of storytelling on celluloid, and this exhibition is highly recommended.

Stanley Kubrick: The Exhibition, continues at the Design Museum, Kensington High Street, until 15th September 2019. The exhibition is open daily from 10am to 6pm (last admission 5pm). Tickets are free for Members, £16 for adults and £12 for students, with other concessions and family tickets available. More information is available here: https://designmuseum.org/exhibitions/stanley-kubrick-the-exhibition