Hylaeosaurus was a 15 foot long armored dinosaur which lived in England (and possibly elsewhere in Europe) during the early Cretaceous Period approximately 135 million years ago.

The bones of this animal were discovered in July 1832 within Tilgate Forest, Sussex, England. In November of that same year, Dr. Gideon Mantell (the same scientist who named Iguanodon) named this animal Hylaeosaurus, meaning “forest lizard” in reference to where it was found. The species name armatus, meaning “armed”, referred to the creature’s long weapon-like spikes (Dean 1999, pages 110-125).

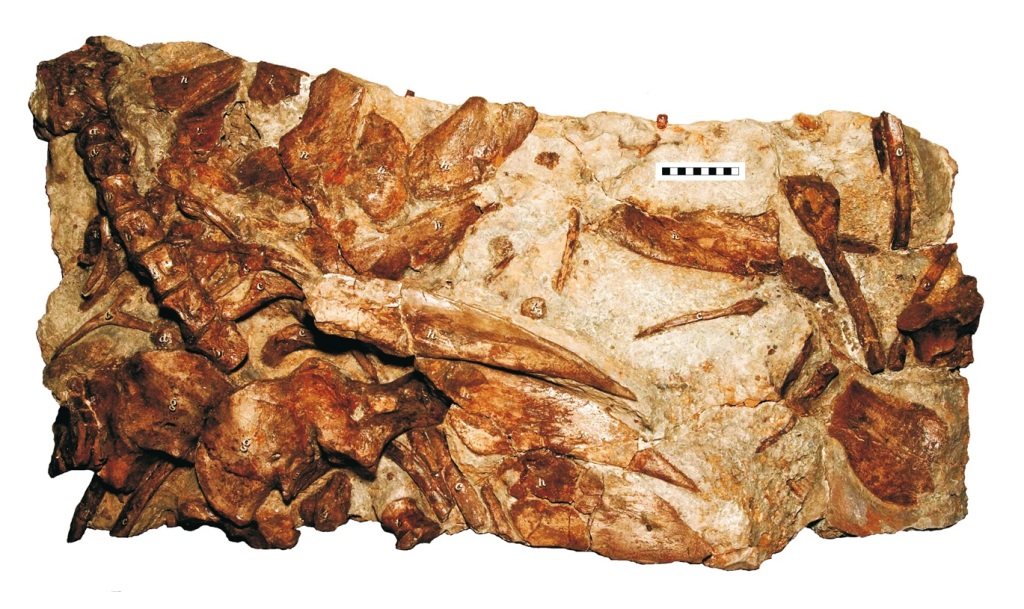

The holotype specimen of Hylaeosaurus armatus (collection ID code: NMH R3775), found in Tilgate Forest, Sussex, England. Sachs, Sven; Hornung, Jahn, J. (2013). “Ankylosaur Remains from the Early Cretaceous (Valanginian) of Northwestern Germany”. PLoS ONE, volume 8, issue 4 (April 3, 2013): e60571. Creative Commons Attribution 2.5 Generic license.

Mantell believed that these spines extended in a row down the middle of the animal’s back, but this was disputed by the renowned British anatomist Sir Richard Owen (Mantell 1849, page 284). Owen furthermore stated that the specimen which was found in 1832 belonged to an immature individual (Owen 1841, page 117). In 1842, Owen used Iguanodon, Hylaeosaurus, and Megalosaurus as the basis for establishing the group Dinosauria (Owen 1942, page 103).

The fossils of Hylaeosaurus were uncovered within the “Hastings Group”, which was deposited during the early Cretaceous Period. This geological group is divided into three formations which are, listed from oldest/lowest to newest/highest: the Ashdown Formation, the Wadhurst Clay Formation, and the Tunbridge Wells Sands Formation. Hylaeosaurus is known from the middle part of the Tunbridge Wells Sands Formation, which would date it to the upper Valanginian Stage of the early Cretaceous, approximately 135 million years ago (Raven 2019, pages 11, 23). Hylaeosaurus is one of only three species of armored dinosaurs known from southern England during the early Cretaceous Period. The second is Vectipelta barretti, which is known from the lower part of the Isle of Wight’s Wessex Formation, around 132-130 MYA (Pond et al 2023, pages 1, 3, 6, 37). The third is Polacanthus foxii, whose fossils were also found in the Wessex Formation, dated to the Barremian Stage of the early Cretaceous about 125 MYA (Raven 2019, pages 23, 40)

Hylaeosaurus shared its prehistoric English habitat with the brachiosaurid sauropod Pelorosaurus, the large iguanodontid Barilium, the smaller ridge-backed iguanodontid Hypselospinus, the 12 foot dryosaurid Valdosaurus, the 12-15 foot stegosaur Regnosaurus, the 20-25 foot ridge-backed theropod Altispinax, and the somewhat dubious spinosaurid theropod Suchosaurus. Meanwhile, swimming in the water offshore was the 15 foot pliosaur Hastanectes, and several species of fish including at least three different species of hybodont sharks. Flying in the sky overhead were the pterosaurs Serradraco and Coloborhynchus.

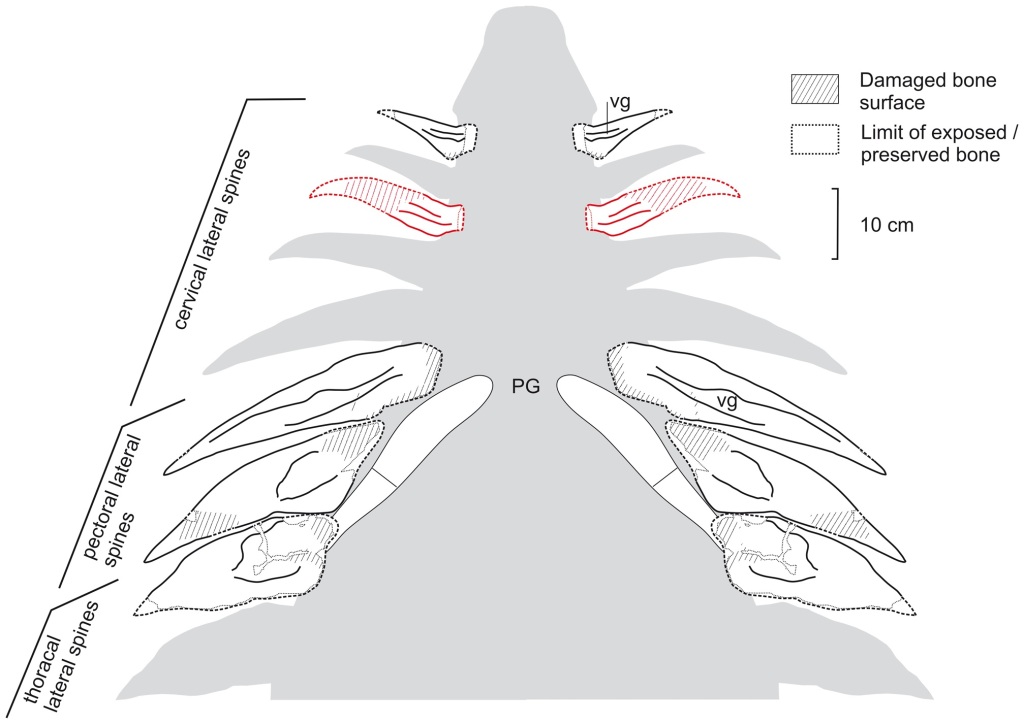

Although Hylaeosaurus is known from southern England, other fossils which might belong to Hylaeosaurus have also been found in Spain (Sanz 1983), France (Corroy 1922), Germany (Sachs and Hornung 2013), and Romania (Posmosanu 2003). However, there have been very few remains found within these locations and the fossils are difficult to positively identify. These specimens might belong to Hylaeosaurus, but it’s also possible that they could belong to the related genera Polacanthus, Vectipelta, or possibly to some other armored dinosaur.

A hypothetical reconstruction of the lateral cervico-thoracal armor in Hylaeosaurus armatus, ventral view. Specimens shown are “NMH R3775” from southern England (white elements) and “DLM 537” from northwestern Germany (red element). Abbreviations: PG, pectoral girdle (approx. position, schematic); vg, ventral groove. Sachs, Sven; Hornung, Jahn, J. (2013). “Ankylosaur Remains from the Early Cretaceous (Valanginian) of Northwestern Germany”. PLoS ONE, volume 8, issue 4 (April 3, 2013): e60571. Creative Commons Attribution 2.5 Generic license.

It’s difficult to decide where a particular species fits onto the family tree based upon scant physical remains. However, based upon the few remains which have been found, and by comparing them to other members of Ankylosauria, Hylaeosaurus is believed to have been a primitive member of Nodosauridae, and may have been closely related to the late Jurassic genera Gargoyleosaurus and Mymoorapelta (Thompson et al 2012).

How may we reconstruct Hylaeosaurus based upon its limited remains?

- Based upon the size of the few Hylaeosaurus fossils which have been found, and comparing them to the size of the bones of other ankylosaurians, Hylaeosaurus is estimated to have measured about 15 feet long (Natural History Museum. “Hylaeosaurus”).

- Portions of the back of Hylaeosaurus‘ skull were found, and an analysis of these skull fragments in 2001 showed that they were similar to that of Gargoyleosaurus (Carpenter 2001, pages 169-172), and therefore the head of Hylaeosaurus may have looked similar to it.

- Fossil evidence infers that this creature was bristling with a formidable row of curved scythe-like spines running along each side of its body. Both Gargoyleosaurus and Mymoorapelta also had a row of laterally-projecting blade-like osteoderms on each side of its body, but the ones seen on the holotype of Hylaeosaurus appear to have been both longer and narrower.

- According to William Blows, Hylaeosaurus‘ body armor was more primitive compared to that of Polacanthus (Blows 1998, page 33). This lines up with the prevailing sentiment that Hylaeosaurus was closely related to the primitive ankylosaurians like Gargoyleosaurus and Mymoorapelta (Thompson et al 2012). The osteoderms which covered the back of these two animals are frequently reconstructed in a staggered pattern rather than being arranged in neat rows. However, it must be said that there is no hard evidence which definitely proves that the osteoderms were arranged this way in life.

- The armored pelvic shield was composed of randomly-placed irregularly-sized oval and circular osteoderms, some of which had keels, interbedded amongst smaller polygonal bony “ossicles” which were all fused together. Such armor was also seen in creatures like Gargoyleosaurus, Gastonia, and Polacanthus. (Arbour et al 2011, page 300).

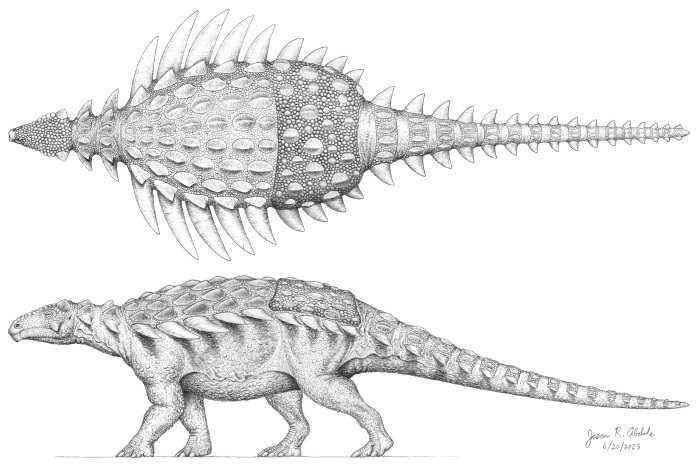

Below is an illustration which I made of what Hylaeosaurus might have looked like from both an overhead view and sideways view, based upon the few skeletal remains which have been found and merging it with skeletal features of other primitive ankylosaurians. Although a complete or even partial skull of Hylaeosaurus hasn’t been found, the few fragments which have been found show similarity to Gargoyleosaurus, so this animal was portrayed as having a Gargoyleosaurus-like skull. The top of the skull would have been flat or slightly convex, and festooned with a multitude of short conical or rounded bumps similar to that seen on the top of the skull of the pachycephalosaur Dracorex (which might be a juvenile Pachycephalosaurus, but that’s debatable). It’s likely that Hylaeosaurus didn’t possess any upwards-pointing osteoderms on its back like those seen in Gastonia. Instead, Hylaeosaurus‘ back would have been covered with multiple rows of low oval-shaped keeled osteoderms similar to that seen in Gargoyleosaurus. Its back and sections of its tail are covered in larger thicker polygonal scales, while the flexible areas in between are covered in smaller pebbly scales.

This drawing was one of the most difficult artworks which I’ve ever made. Since I intended to illustrate the same animal in two different views, I needed to make sure that all of the various anatomical features lined up exactly. Considering that this animal is covered with lots of bumps, spikes, and knobs of varying sizes, this was rather daunting. This illustration took almost a month to complete. The drawing measures 15 inches long (1/12 scale) from nose to tail, and was made with No.2 and No.3 pencils on printer paper.

Hylaeosaurus armatus. © Jason R. Abdale (June 20, 2023).

If you enjoy these drawings and articles, please click the “like” button, and leave a comment to let me know what you think. Subscribe to this blog if you wish to be immediately informed whenever a new post is published. Kindly check out my pages on Redbubble and Fine Art America if you want to purchase merch of my artwork.

Keep your pencils sharp.

Bibliography

Arbour, Victoria, M.; Burns, Michael E.; Currie, Philip J. (2011). “A Review of Pelvic Shield Morphology in Ankylosaurs (Dinosauria: Ornithischia)”. Journal of Paleontology, volume 85, issue 2 (2011). Pages 298-302.

https://www.academia.edu/82812131/A_review_of_pelvic_shield_morphology_in_ankylosaurs_Dinosauria_Ornithischia_.

Blows, William T. (1998). “A Review of Lower and Middle Cretaceous Dinosaurs of England”. In Lucas, S.G.; Kirkland, James I.; Estep, J.W., eds. Lower and Middle Cretaceous Terrestrial Ecosystems. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin 14. Pages 29-38.

https://www.google.com/books/edition/Lower_and_Middle_Cretaceous_Terrestrial/yF4fCgAAQBAJ?hl=en&gbpv=0.

Carpenter, Kenneth (2001). “Skull of the polacanthid ankylosaur Hylaeosaurus armatus Mantell, 1833, from the Lower Cretaceous of England”. In Carpenter, Kenneth, ed., The Armored Dinosaurs. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2001. Page 169-172.

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/314984590_Skull_of_the_polacanthid_ankylosaur_Hylaeosaurus_armatus_Mantell_1833_from_the_Lower_Cretaceous_of_England.

Corroy, G. (1922). “Les reptiles néocomiens et albiens du Bassin de Paris”. Comptes Rendus de l’Académie des Sciences de Paris, volume 172 (1922). Pages 1192–1194.

https://orage.univ-lorraine.fr/s/orage/item/13051.

Dean, Dennis R. Gideon Mantell and the Discovery of Dinosaurs. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999.

Mantell, Gideon Algernon. Observations on the Osteology of the Iguanodon and Hylaeosaurus. London: R & J. E. Taylor, 1849.

https://www.google.com/books/edition/Observations_on_the_Osteology_of_the_Igu/fYsxgg1t9_sC?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=Hylaeosaurus+1832&pg=PA284&printsec=frontcover.

Owen, Richard. Report on British Fossil Reptiles, Part II. London: Richard and John E. Taylor, 1841.

https://www.google.com/books/edition/Report_on_British_Fossil_Reptiles/mSTs2oyhdS0C?hl=en&gbpv=1.

Owen, Richard. “Report on British Fossils”. Report of the Eleventh Meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science. London: John Murray, 1842. Pages 60-204.

https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=njp.32101076796059&view=1up&seq=145.

Pond, Stuart; Strachan, Sarah-Jane; Raven, Thomas J.; Simpson, Martin I.; Morgan, Kirsty; Maidment, Susannah C. R. (2023). “Vectipelta barretti, a new ankylosaurian dinosaur from the Lower Cretaceous Wessex Formation of the Isle of Wight, UK”. Journal of Systematic Palaeontology, volume 21, issue 1 (June 15, 2023). Pages 1-42.

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/epdf/10.1080/14772019.2023.2210577.

Posmosanu, Erika (2003). “The palaeoecology of the dinosaur fauna from a Lower Cretaceous bauxite deposit from Bihor (Romania)”. Acta Palaeontologica Romaniae, volume 4 (2003). Pages 431-439.

https://actapalrom.geo-paleontologica.org/APR_vol_4/39Posmosanu.pdf.

Raven, Thomas L. (2019). “The taxonomic, phylogenetic, biogeographic and macroevolutionary history of the armoured dinosaurs (Ornithischia: Thyreophora)”. PhD thesis, University of Brighton. Pages 1-649.

https://cris.brighton.ac.uk/ws/portalfiles/portal/23893138/Raven_PhD_Thesis.pdf.

Sachs, Sven; Hornung, Jahn, J. (2013). “Ankylosaur Remains from the Early Cretaceous (Valanginian) of Northwestern Germany”. PLoS ONE, volume 8, issue 4 (April 3, 2013): e60571.

https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0060571.

Sanz, Jose Luis (1983). “A nodosaurid ankylosaur from the Lower Cretaceous of Salas de los Infantes (Province of Burgos, Spain)”. Geobios, volume 16, issue 5 (1983). Pages 615–621.

Thompson, Richard S.; Parish, Jolyon C.; Maidment, Susannah C. R.; Barrett, Paul M. (2012). “Phylogeny of the ankylosaurian dinosaurs (Ornithischia: Thyreophora)”. Journal of Systematic Palaeontology, volume 10, issue 2 (June 2012). Pages 301-312.

Natural History Museum. “Hylaeosaurus”. https://www.nhm.ac.uk/discover/dino-directory/hylaeosaurus.html. Accessed on June 2, 2023.

Categories: Paleontology, Uncategorized

Leave a comment