The Beatles’ imagined India was a stronger muse than the real one

‘The Beatles and India’ documentary reveals a bitter experience with a guru that changed them in unexpected ways

The connection between the Beatles and India (now it would labeled cultural appropriation) was genuinely heartfelt. The United Kingdom’s pop culture in the 1960s was captivated by its largest former colony, and Indian music for the UK’s thriving immigrant community was all over the radio. It comes as no surprise that the Beatlemania sweeping the planet also made its way to India, where local bands eagerly sought to emulate the look and music of the Liverpool-born phenomenon. This bond is eloquently depicted in The Beatles and India, a well-researched and insightful British documentary film released in 2021. However, due to copyright restrictions, the film regrettably doesn’t feature any of the Fab Four’s iconic songs.

Directed by Ajoy Bose (author of Across the Universe: The Beatles in India) and Peter Compton, the documentary interviews both Brits and Indians with firsthand knowledge of how the Beatles passionately embraced Indian music even before their first visit in 1966. Their journey to Rishikesh in 1968 to meditate with Maharishi Mahesh Yogi was a transformative experience that left a lasting impact — but not the one they expected.

The first interaction of the Beatles with India that the world saw was in their 1965 movie Help! The villains were an Indian band who reinforced every imaginable stereotype in a series of improbable situations. The always restless George Harrison became captivated by the sitar sound, so he bought one and found a teacher. He was Ravi Shankar, a musician from Benares (India) who enjoyed a measure of fame in Europe and ended up performing at the Monterey and Woodstock music festivals. We first heard Harrison’s sitar in the Lennon-penned Norwegian Wood from the Rubber Soul album (1965).

The Indian influence blended seamlessly with the Beatles’ golden era. It was a sound that resonated with the hippie spiritual quest and especially George Harrison. The psychedelic wave of LSD experimentation further transformed the exotic, mesmerizing music. The Beatles stopped touring to concentrate on songwriting and recording, freeing themselves from the stylistic constraints of their early music. The turning point was Revolver (1966), which featured Harrison’s laconic sitar on Love You To and Lennon’s hypnotic Tomorrow Never Knows.

The Beatles briefly stopped in Delhi in July 1966 on their return from the Philippines. The legendary band performed two concerts before 80,000 rabid fans in Manila, but their apparent snub of Imelda Marcos, the country’s first lady and wife of President Ferdinand Marcos, ignited a media frenzy. George Harrison returned to India later that year to work with local musicians on his debut solo album, Wonderwall Music. He even took a selfie at the Taj Mahal.

Harrison penned more Beatles songs featuring his sitar-playing, including Within You Without You, and Inner Light. However, he realized that becoming a sitar master was unlikely, as even his teacher, Ravi Shankar, was still learning the instrument. Harrison later wrote Blue Jay Way, another Indian-inspired song (without the sitar) for the trippy Magical Mystery Tour album.

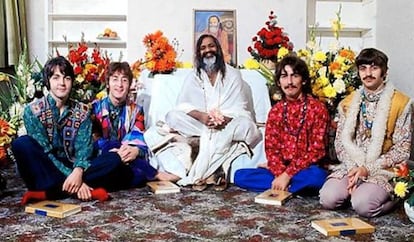

In early 1968, the Beatles found themselves at a crossroads. Their Magical Mystery Tour made-for-TV movie was widely panned, signaling the end of their psychedelic phase. The death of Beatles manager Brian Epstein profoundly affected the band, as he had been their glue. Seeking clarity, they traveled to India for a meditation course led by Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, who had become a popular spiritual figure in San Francisco. The Beatles and several of the Rolling Stones had previously met the guru in Wales. Accompanying the Beatles were notable musicians, artists and actors like Donovan, Mia Farrow, Mike Love (Beach Boys), jazz musician Paul Horn, photographer and producer Paul Saltzman and journalist Lewis Lapham. Together, they journeyed to the foothills of the Himalayas in search of solace and enlightenment.

Regrettably, the quest for spiritual enlightenment was marred by human failings and worldly concerns. The guru attempted to exploit the popularity of his famous students and wanted to film a documentary with them, which the Beatles declined. When he made sexual advances toward Farrow, wanting to merge in a “cosmic hug,” she promptly left, shattering the purity of the experience. However, Lennon and McCartney still found inspiration and returned with almost 50 songs. Many were recorded for the White Album, and some made it onto later albums.

The Beatles and India depicts very different experiences for the Beatles during their retreat with Maharishi Mahesh Yogi. Ringo and his wife Maureen only lasted 10 days and Paul left after three weeks. George and John stuck with the guru for about six weeks, after which Harrison stayed in India to visit Madras. Lennon left angry, feeling used. He wrote a song called Maharishi about the experience but later reworked and renamed it Sexy Sadie. “You made a fool of everyone / Sexy Sadie, ooh, what have you done / Sexy Sadie, you broke the rules / You laid it down for all to see.”

The film ends there. It would have been interesting to analyze the White Album, recorded upon their return. The album didn’t have sitars, outlandish outfits or psychedelic trips. Instead, it offered 30 songs with a leaner sound — guitar, bass, drums and piano. The Indian influence is less apparent, except perhaps in Lennon’s single-chorded Dear Prudence, dedicated to Mia Farrow’s sister. The album notably excluded Across the Universe, Lennon’s Indian-inspired composition that made a later appearance on Let it Be. While Harrison temporarily set aside his Indian explorations, he would collaborate again with Ravi Shankar and organized the memorable benefit concert for Bangladesh. Harrison was always the “Spiritual” Beatle. In the White Album, you can sense that each Beatle is heading in a different direction. By mid-1969, the band had broken up.

Experiencing the real India, rather than an imagined version, pushed the Beatles’ music in an unexpected direction. Instead of leading to more lush, exotic sounds, the band leaned toward simplicity. The influence of India became more nuanced, more authentic. But after venturing on this journey of self-discovery, each Beatle ultimately found himself making music alone.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition