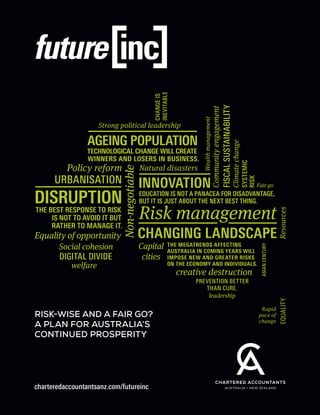

Risk-wise and a fair go? A plan for Australia’s continued prosperity.

- 1. charteredaccountantsanz.com/futureinc RISK-WISE AND A FAIR GO? A PLAN FOR AUSTRALIA’S CONTINUED PROSPERITY Community engagement Non-negotiable Equality of opportunity Capital cities welfare Policy reform Climate change Wealth management leadership SYSTEMIC RISK Resources creative destruction PREVENTION BETTER THAN CURE. CHANGE IS INEVITABLE DIGITAL DIVIDE Risk management Natural disasters Fair go Social cohesion Strong political leadership Rapid pace of change AGEING POPULATION INNOVATION DISRUPTION CHANGING LANDSCAPE EQUALITY THE BEST RESPONSE TO RISK IS NOT TO AVOID IT BUT RATHER TO MANAGE IT. EDUCATION IS NOT A PANACEA FOR DISADVANTAGE, BUT IT IS JUST ABOUT THE NEXT BEST THING. TECHNOLOGICAL CHANGE WILL CREATE WINNERS AND LOSERS IN BUSINESS. FISCAL SUSTAINABILITY ASIAN CENTURY URBANISATION THE MEGATRENDS AFFECTING AUSTRALIA IN COMING YEARS WILL IMPOSE NEW AND GREATER RISKS ON THE ECONOMY AND INDIVIDUALS.

- 2. Chartered Accountants Australia and New Zealand Chartered Accountants Australia and New Zealand is made up of over 100,000 diverse, talented and financially astute professionals who utilise their skills every day to make a difference for businesses the world over. Members of Chartered Accountants Australia and New Zealand are known for professional integrity, principled judgement, financial discipline and a forward-looking approach to business. We focus on the education and lifelong learning of members, and engage in advocacy and thought leadership in areas that impact the economy and domestic and international capital markets. We are a member of the International Federation of Accountants, and are connected globally through the 800,000-strong Global Accounting Alliance and Chartered Accountants Worldwide which brings together leading Institutes in Australia, England and Wales, Ireland, New Zealand, Scotland and South Africa to support and promote over 320,000 Chartered Accountants in more than 180 countries. Chartered Accountants Australia and New Zealand is a trading name for The Institute of Chartered Accountants in Australia (ABN 50 084 642 571) and the New Zealand Institute of Chartered Accountants – see charteredaccountantsanz.com for further information. Deloitte Access Economics is Australia’s pre-eminent economics advisory practice and a member of Deloitte’s global economics group. For more information, please visit our website www.deloitteaccesseconomics.com.au About Deloitte Deloitte refers to one or more of Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu Limited, a UK private company limited by guarantee, and its network of member firms, each of which is a legally separate and independent entity. Please see www.deloitte.com/au/about for a detailed description of the legal structure of Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu Limited and its member firms. About Deloitte Australia In Australia, the member firm is the Australian partnership of Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu. As one of Australia’s leading professional services firms. Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu and its affiliates provide audit, tax, consulting, and financial advisory services through approximately 6,000 people across the country. Focused on the creation of value and growth, and known as an employer of choice for innovative human resources programs, we are dedicated to helping our clients and our people excel. For more information, please visit our web site at www.deloitte.com.au Liability limited by a scheme approved under Professional Standards Legislation. Member of Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu Limited. Copyright © November 2014 Chartered Accountants Australia and New Zealand. All rights reserved. DISCLAIMER This was prepared by Chartered Accountants Australia and New Zealand with the assistance of Deloitte Access Economics. This publication contains general information only, none of Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu Limited, its member firms, or their related entities (collectively the “Deloitte Network”) nor Chartered Accountants Australia and New Zealand are, by means of this publication, rendering professional advice or services. Before making any decision or taking any action that may affect your finances or your business, you should consult a qualified professional adviser. No warranty is given to the correctness of the information contained in this publication, or its suitability for use by you. To the fullest extent permitted by law, no liability is accepted by Chartered Accountants Australia and New Zealand or any entity in the Deloitte Network for any statement or opinion, or for any error or omission or for any loss whatsoever sustained by any person who relies on this publication. Chartered Accountants Australia and New Zealand is a trading name for The Institute of Chartered Accountants in Australia (ABN 50 084 642 571) and the New Zealand Institute of Chartered Accountants – see charteredaccountantsanz.com for further information. 1114-3

- 3. FOREWORD If Australia was a business – and in many respects it exhibits similar fundamental features to any ordinary business – success could be highly dependent on whether or not sufficient time has been invested in planning its strategy and clearly defining its market position, goals and objectives. This thought kick-started our future[inc] thought leadership series about 18 months ago. We wanted to look at major economic and social megatrends and the impact they could have on our ability to compete internationally. We discussed Australia’s strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats concluding that whilst we will no doubt benefit from the major growth engines of the 21st century, we can’t be complacent when planning and applying policies that could either hamper future generations of Australians, or which could contribute to a better way of life for our children’s children. Since then, future[inc] has also looked at how we measure the success of a nation and posed the question ‘Is it time to move beyond measuring national progress with GDP?’. We published ‘A Plan for New Zealand’s Continued Prosperity’ and ‘An Economic Policy Platform for the Next Term of Government’. Mel Ashton FCA President designate We’ve also looked at cyber security, as cyber crime now, more than ever before, poses a major threat to individuals and businesses. Indeed, it could herald the next financial crisis and is becoming one of the hot topics for boards and CEOs. Our intention with future[inc] was to fill a void that we believe exists in our current policy debate. This paper, ‘Risk-wise and a Fair Go? A Plan for Australia’s Continued Prosperity’ takes our thinking to a more granular level by focusing on our attitudes to risk, and questioning whether Australia is in danger of losing its ‘fair-go’ image – which would be very un-Australian. I’d like to thank the team at Deloitte Access Economics and the many individuals at Chartered Accountants who contributed to the thinking in this paper. I look forward to continuing the debate with you. charteredaccountantsanz.com/futureinc

- 4. … WHAT WOULD THE ATTRIBUTES OF INCLUSIVE CAPITALISM BE? Trust, opportunity, rewards for all within a market economy – allowing everyone’s talents to flourish. Certainly, that is the vision. CHRISTINE LAGARDE, MAY 20141

- 5. CONTENTS 06 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 08 INTRODUCTION 10 THE CHANGING LANDSCAPE 17 MEGATRENDS 24 RISK 33 AUSTRALIA: LAND OF THE FAIR GO? 44 CONCLUSION 46 REFERENCES

- 6. RISK-WISE AND A FAIR GO? A PLAN FOR AUSTRALIA’S CONTINUED PROSPERITY 6 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Policy is developed in an increasingly changing landscape. The global financial crisis has influenced economic policy and outcomes for much of the last decade and the developed world is still feeling its effects. Australia and New Zealand have benefited greatly from the rise of Asia in recent decades but we cannot take this prosperity for granted. Looking forward, several trends are likely to dominate the environment in which policy is made. In addition to the rising importance of Asia, the list of ‘megatrends’ includes an ageing population, urbanisation and the advancing technology frontier. These forces cannot be avoided; instead, policy must adapt to make the most of the opportunities they present and to manage their disruptive impacts. Eighteen months have passed since the launch of ‘Developing a Plan for Australia’s Economic Prosperity’, yet while we have seen a change of government and numerous reviews, in many respects the issues facing Australia into the future remain largely unchanged. This paper extends our thought leadership into new areas – areas that are exposed in public debate but still require consideration as part of a broader policy discussion. Specifically, they include risk and equity, and the roles and responsibilities of businesses, individuals and governments in dealing with the associated challenges.

- 7. 7 future[inc] RISK Are we as individuals and as a nation approaching risk in the right way? Wellbeing can be improved by raising income, but this also requires managing the uncertainties around that income. Aggregates such as GDP provide one measure of welfare but ignore the uncertainties or risks that people face. The notion in financial markets that there is a trade-off between risk and return holds more generally. Over time we appear to have become a more risk-averse society, with people increasingly looking to government to regulate away potential risks. But avoiding risk carries cost, both in terms of the compliance burden imposed on business and government and in limiting the power of ‘creative destruction’ to deliver welfare-enhancing innovation. The best response to risk is not to avoid it, but rather to manage it. Policy should seek to measure aggregate risks and ensure that they are borne by those best placed to do so. Of concern is that the policy response will seek to avert risk rather than manage it. The issue is not whether we should be risk-averse or risk-seeking, but rather that we should be more literate and better informed about risk—that is, we should become risk-wise. AUSTRALIA: LAND OF THE FAIR GO? Australia’s self-image typically highlights the notion of a ‘fair go’: the idea that any of us should have the opportunity to get ahead regardless of his or her circumstances. While high levels of social mobility have tended to support this self-image, increasing disparities in income between the wealthiest and the poorest among us are challenging this view. On several key measures of equality, Australia’s performance is only ‘average’ by developed-world standards. International Monetary Fund (IMF) and Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) studies show that, beyond a point, wider dispersion of income can both increase social tension and decrease economic growth. In such circumstances there is a role for government to address the worst inequalities through tax and transfer mechanisms. The megatrends – especially globalisation and new technologies – are raising wealth levels overall but are also widening the dispersion of outcomes. This reflects the market at work, as individuals and businesses take advantage of the opportunities provided. The challenge for policy is how best to foster economic growth while ensuring that the more vulnerable members of society are not left behind. Policies directed at creating equality of opportunity are the starting point when dealing with inequality, especially policies aimed at increasing participation by those marginalised from the labour force. Indeed, increasing the engagement of these people will deliver double-dividend outcomes, where both the size of the national income pie grows and much of the growth accrues to those who previously received the smallest portion. Bipartisan support for the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS) shows that such policies can be implemented. Policies that allow the market to work coupled with policies directed at promoting equality of opportunity are essential. If Australians are to emerge from these challenges at least as well off as we enter them, strong political leadership will be required. Short-term political and budgetary pressures often work against long-term solutions, but engagement with the community and building the case for reform can help align these priorities.

- 8. RISK-WISE AND A FAIR GO? A PLAN FOR AUSTRALIA’S CONTINUED PROSPERITY 8 INTRODUCTION In April 2013, Chartered Accountants Australia and New Zealand (then the Institute of Chartered Accountants Australia) launched the future[inc] series with the release of Developing a Plan for Australia’s Economic Prosperity. It highlighted long-standing areas of policy debate: productivity, infrastructure investment, federalism, balancing economic growth, fiscal sustainability, and climate change. Collectively, the issues identified encompass many of the policy challenges facing Australia now and in the future. The policy landscape has shifted over the past 18 months: • there has been a change of federal government and a corresponding shift of policy direction in a number of key areas; • the National Commission of Audit handed down its report on government spending, parts of which were incorporated into the May 2014 Federal Budget; • the Productivity Commission has embarked on new reviews, including into child care and natural disasters; and • a number of dedicated policy inquiries have been announced and commenced their work, including: –– the Murray Financial System Inquiry (FSI); –– the Harper Competition Policy Review; –– the Vertigan Review of the market and regulation of the National Broadband Network (NBN); and –– the Commonwealth White Papers on tax, defence agriculture and reform of the Federation.

- 9. 9 future[inc] Given these developments, it is important to understand what progress has been made since April 2013 and how the policy goals have shifted. It should also be noted that, taken together, these reviews represent a significant number of large-scale policy agendas being tabled within a relatively short period of time. To elevate this discussion above the noisy policy environment, there is a greater focus on anticipating or ‘foresighting’ longer-term ‘megatrends’ that policymakers will have to contend with. Some trends can be projected with greater accuracy than others; the ageing population and evolving technology being two examples at opposite ends of the predictability spectrum. However, the common factor is that these developments will unfold regardless of the shorter-term policy measures that are put in place. There is uncertainty about how these trends will affect society and individuals, and about the risks we will be facing. Clearly, the best way for society to meet the big challenges is to enable everyone to contribute to the best of their ability. Consequently, the policy framework needs to accommodate both the risk and equity dimensions. How we manage risk in our economy and in social policymaking is important. Current thinking and evidence in the area suggests that poor allocation and management of risk is constraining the economy. Further, the ways that risk is borne and flows around our economy are changing, as a result of the long-term megatrends we face now and into the future. The risk-taking behaviour associated with the GFC has dominated the airspace in recent times. While there are clear policy lessons from that episode, there is a need for a separate public conversation about risk. The megatrends will affect people in different ways. Inequality has been increasing over time in almost all countries for which reliable data is available. In some parts of the world this is starting to undermine social cohesion, a cost which cannot easily be captured in GDP or measurements of income dispersion. Apart from their impacts on the economy in aggregate, the megatrends need to be explored to understand their effect on income and wealth distribution, to ensure that the equity of Australia’s society is not diminished and all parts of our society benefit from collective progress. The policy measures of today need to maintain a healthy balance of both equity and growth into the future. To elevate this discussion above the noisy policy environment, there is A GREATER FOCUS ON ANTICIPATING or ‘FORESIGHTING’ LONGER-TERM ‘MEGATRENDS’ that policymakers will have to contend with. For more insights go to + charteredaccountantsanz.com/futureinc

- 10. RISK-WISE AND A FAIR GO? A PLAN FOR AUSTRALIA’S CONTINUED PROSPERITY 10 THE CHANGING LANDSCAPE CHANGING POLICY LANDSCAPE STATE OF PLAY AND THE SWOT ANALYSIS 01 02

- 11. 11 future[inc] Australia is in a fortunate position, with a history of strong institutions and policymaking, a well educated population and an endowment of natural wealth. However, these factors should not be taken for granted; nor should they be seen as sufficient to overcome all future challenges posed by rapidly changing technology and geographical shifts of economic power. Strong leadership will be required to introduce the policy reforms that inevitably will be needed: ‘leadership of vision, leadership of thinking and leadership of communication’.2 Evidence-based policy has produced some of the largest economic gains in Australia’s economic development. Microeconomic reforms of the 1980s and 90s were politically difficult to implement but yielded significant gains to the community. Despite the clear gains from such policy formulation, there are aspects of today’s policymaking environment that have shifted the scales against it. 01 CHANGING POLICY LANDSCAPE Governments use their first terms to define their leadership on both social and economic issues. As with many first-term governments, the Coalition has set in motion a series of policy reviews and inquiries to identify policy options for the future. There are both benefits and costs to this approach. On the one hand, inquiries and reviews can provide the information and consultation needed to inform sound policy decisions. But too many inquiries can lead to confusion and the possibility that interrelated issues are siloed in separate reviews. … too many inquiries can lead to confusion and can silo interrelated issues into separate reviews. Spark your interest at + charteredaccountantsanz.com/futureinc EVIDENCE-BASED POLICY HAS PRODUCED SOME OF THE LARGEST ECONOMIC GAINS in Australia’s economic development. Microeconomic reforms of the 1980s and 90s were politically difficult to implement but yielded significant gains to the community.

- 12. RISK-WISE AND A FAIR GO? A PLAN FOR AUSTRALIA’S CONTINUED PROSPERITY 12 Reducing red tape whole of government initiative Tax Financial Advisers Regulation Competition Inquiry Senate Inquiry into the role of ASIC Senate Inquiry into FoFA Amendments Review of retirement income stream regulation Review of financial advice in relation to SMSFs Tax Reform White Paper Financial Systems Inquiry Parliamentary Joint Committee into professional, ethical and education standards in the financial services industry Cooper Review/Stronger Super reforms – governance and efficiency of super system Senate Economics References Committee: inquiry into forestry managed investment schemes FIGURE 1: CURRENT INQUIRIES AND REVIEWS SOURCE: Chartered Accountants Australia and New Zealand3

- 13. 13 future[inc] Figure 1 shows a subset of the inquiries and reviews currently underway in Australia. When viewed as a Venn diagram, it is clear that the terms of reference of many of the inquiries overlap. In such an environment it is difficult for policymakers to adopt a holistic approach: individual recommendations which make sense in the specific context of one review may not be optimal in a broader context or when combined with the recommendations of other reviews. Independent reviews can be a useful process for consultation and independent analysis of important issues, thereby supporting evidence-based policy. However, it is important that reviews do not defer real action being taken on important issues or represent a missed opportunity for a young government to implement meaningful reforms. Developing a Plan for Australia’s Economic Prosperity identified five key challenges facing evidence-based policy. As Figure 2 shows, many of these pressures are unlikely to disappear soon, meaning that the environment in which decisions are made is unlikely to become any less complex and demanding. OBSTACLES STATUS COMMENTS The three-year electoral cycle of Federal government Unlikely to be resolved Here to stay The 24-hour news cycle Unlikely to be resolved Here to stay Policy capability and talent Unclear magnitude Cuts to the Australian Public Service may reduce capability in the short term Lack of information sharing Unclear magnitude Improvements in some areas but no broad developments Constitutional boundaries and limitations Unclear magnitude Federation White Paper may address this issue but may also undo previous COAG gains SOURCE: Chartered Accountants Australia and New Zealand, Deloitte Access Economics FIGURE 2: OBSTACLES TO EVIDENCED-BASED REFORM Join the debate at + charteredaccountantsanz.com/futureinc

- 14. RISK-WISE AND A FAIR GO? A PLAN FOR AUSTRALIA’S CONTINUED PROSPERITY 14 STATE OF PLAY AND THE SWOT ANALYSIS The last eighteen months have seen a new Federal Government sworn in and some developments in parts of the SWOT analysis. We identify the key changes over this period and how policy developments may shape these themes into the future. STRENGTHS WEAKNESSES • Soundness of economic policy • A strong and resilient economy • Geography, abundant natural resources and close proximity to dynamic emerging Asia • Productivity growth • Infrastructure deficit • Intergovernmental relations and the tax transfer system OPPORTUNITIES THREATS • Global economic structural change • Opportunity for reform • Opportunity for greater diplomatic role • External economic threats • Fiscal sustainability • Climate change SOURCE: Chartered Accountants Australia and New Zealand, Deloitte Access Economics FIGURE 3: SWOT ANALYSIS FROM DEVELOPING A PLAN FOR AUSTRALIA’S ECONOMIC PROSPERITY While we will benefit from the ongoing higher volumes of resource exports, the economy will require STRUCTURAL SHIFTS AWAY FROM THE RESOURCES SECTOR IF RISING UNEMPLOYMENT IS TO BE AVOIDED. 02

- 15. 15 future[inc] STRENGTHS The mining boom has made the transition from the investment phase to the production phase. While we will benefit from the ongoing higher volumes of resource exports, the economy will require structural shifts away from the resources sector if rising unemployment is to be avoided. At the same time prices of bulk commodities have fallen sharply, particularly for the key export commodities of coal and iron ore. While the recent fall in the exchange rate will help cushion this somewhat, the overall effect on national income will be negative. These recent adjustments illustrate that relying on receipts from the mining export boom is not a long-term plan. The transition away from reliance on the resources sector has been anticipated for some time. The challenge now is to create an environment in which surplus capital and labour can be used efficiently elsewhere in the economy. Spending on urban infrastructure is an area where this can be achieved, all the more so as an infrastructure deficit was considered a weakness. The transition away from reliance on the resources sector has been anticipated for some time. The challenge now is to create an environment in which surplus capital and labour can be used efficiently elsewhere in the economy. WEAKNESSES The infrastructure deficit has continued to receive focus, with the agenda largely driven by the States and receiving general support from the Federal Government. Record low interest rates internationally have led to calls for increased spending on infrastructure as a relatively low-cost, high-return stimulus measure for weakened economies. As always, choosing the ‘right’ infrastructure programs will be important. The recent Productivity Commission Public Infrastructure report claimed that, ‘there is an urgent need to comprehensively overhaul processes for assessing and developing public infrastructure projects’4. Given these comments the recent reduction in resourcing for Infrastructure Australia may be a move in the wrong direction, impeding its ability to offer strong independent analysis of proposed infrastructure projects. A second weakness identified in the earlier paper was intergovernmental relations and the tax-transfer system. Over recent years the COAG agenda has made slow but significant progress in education and health reforms, as well as harmonisation of regulations across the States and Territories. It will be important that the recently announced Federation White Paper builds on this agenda. For more insights go to + charteredaccountantsanz.com/futureinc

- 16. RISK-WISE AND A FAIR GO? A PLAN FOR AUSTRALIA’S CONTINUED PROSPERITY 16 THREATS Fiscal sustainability has been brought to the fore by the spending cuts announced in the Federal Budget 2014, foreshadowed by the National Commission of Audit. Whether or not Australia is facing the ‘budget emergency’ being discussed in public debate, some efforts will be needed in the medium term to bring about changes on both the revenue and spending sides of the ledger. If the Government is serious about fiscal reform, the upcoming tax White Paper will provide such an opportunity. A second threat identified was the potentially devastating effects of climate change. The scientific consensus is synthesised in the latest IPCC report: Continued emission of greenhouse gases will cause further warming and long-lasting changes in all components of the climate system, increasing the likelihood of severe, pervasiveandirreversibleimpactsforpeople and ecosystems. Limiting climate change would require substantial and sustained reductions in greenhouse gas emissions which, together with adaptation, can limit climate change risks.5 The consequences of moving now on climate change and being wrong about its impacts are significantly less damaging than doing nothing and the opposite being true. In that sense, climate change policies are insurance policies. The most recent evidence from the IPCC indicates that swift and effective steps need to be taken to reduce emissions. The current government has discontinued the previous mechanism of directly pricing emissions (initially via a tax with the intention of moving to an ETS), which provided incentives for emitters to reduce their emissions. Under the new policy, emitters will tender for payments to reduce emissions. + Spark your interest at charteredaccountantsanz.com/futureinc

- 17. MEGATRENDS THE ASIAN CENTURY THE AGEING POPULATION THE ADVANCING URBANISATION TECHNOLOGY FRONTIER 01 02 03 04

- 18. RISK-WISE AND A FAIR GO? A PLAN FOR AUSTRALIA’S CONTINUED PROSPERITY 18 Planning for the future requires fresh ways of thinking. This chapter adds to the broader narrative by examining the large-scale megatrends that will shape the policy landscape in the decades to come. These megatrends are the ‘non-negotiables’ of Australia’s future. In order to have a conversation about Australia’s future, it’s fundamental to understand the forces that will shape the economy and society over the coming decades. These forces, or megatrends, are macro-scale shifts that cannot be controlled or reversed by changes to business or policymaking. Indeed, they are the ‘non-negotiables’ of Australia’s future. Here we focus on four of the megatrends: • the Asian century; • the ageing population; • urbanisation; and • the new technology frontier. The common denominator for all of these topics is the increased pace of change, relative to 20 years ago. The New Zealand policy landscape provides an interesting point of comparison for Australia, as shared issues are being dealt with in different ways. The urban sprawl of major cities and the ageing population are two such examples discussed in this chapter. THE ASIAN CENTURY Besides the GFC, the largest event in recent world economic history has been the rise of Asia. The economy of the Asian region has been growing at an average annual rate of approximately 6.4% since 2000; the rest of the world grew at 3.8% over the period6,7. This has led to a shift in the economic centre of gravity progressively toward Asia. China is clearly playing the lead role in the Asian century story, but there are several other countries that have similar growth trajectories. This growth is not just evident in GDP figures but also in other social, economic, and financial indicators: • net primary school enrolment rates increased from 79% in 2000 to 93% in 2011 in South and South-West Asia;8 • the average annual growth in merchandise trade over the past 20 years has been 12.7%;9 and • combined financial market capitalisation annual average growth over the past ten years for India, China, Indonesia Malaysia and Philippines has been 35%.10 Healthy international trade is a function of the political as well as commercial ties between countries. There needs to be an appreciation that engaging with Asia is a two-way street. Much like the ‘diversity dividend’ from immigration, greater openness to foreign business will create a dividend of its own. Foreign investment policy must be shaped with this two-way street in mind. Much like the ‘diversity dividend’ from immigrationpolicy, greateropennesstoforeign business will create a dividend of its own. 01

- 19. 19 future[inc] THE AGEING POPULATION While demographic change is the most gradual and predictable of the megatrends canvassed here, it has large economic and social implications. Future demographic change in Australia will be dominated by the ageing population, with trends in immigration playing a secondary role. The number of older Australians is expected to increase dramatically by 2040: the number of people aged 65 and over will double, and those aged 85 years and over will almost triple.15 By 2040 the number of people aged 65 and over will double, and those aged 85 years and over will almost triple. Building the lucky country It is not a secret that Australia has already benefited greatly from the economic rise of Asia over the past 20 years. But the economic mega-boom in Asia is shifting gears. Asia will soon count for over half the global middle class, projected to reach 3.2 billion by 2030.11 The Australian economy needs to adapt to this shift in investment and export-led growth to consumption-led growth, by developing sectors of the economy including: • Agribusiness; • Natural Gas; • International Education; • Tourism; and • Wealth Management.12 These industries are facing increased demand from Asia. In 2013 international education generated $15.6 billion in exports from the Australian economy.13 China visitor arrivals have more than tripled in the past decade.14 Collectively, unlocking the potential of these sectors could add $250 billion to the Australian economy over the next 20 years. Policy initiatives to facilitate trade with Asian nations will help realise the growth potential of these and other sectors. 02 Want to learn more? + charteredaccountantsanz.com/futureinc

- 20. RISK-WISE AND A FAIR GO? A PLAN FOR AUSTRALIA’S CONTINUED PROSPERITY 20 • changing spending patterns: Older people generally spend more on essential services such as healthcare, rather than discretionary services, such as holidays and recreation. Healthcare largely cannot be imported, so we need to grow this industry at home.18 • a changing fiscal outlook: Figure 4 shows the projected fiscal gap over the coming decades as estimated in the three previous editions of the Treasury’s Intergenerational Report (IGR). The long-term outlook is consistently one of large-scale budget deficits, as a result of demographic change. This has clear impacts on the economy, through: • a relative reduction in labour supply: The age dependency ratio is the number of people outside working age relative to the population of working age (15 – 65). Projections indicate that the dependency ratio will rise from 49.4 in 2012 to 59.5 by 2040.16 Western Australia, the State with the lowest dependency ratio, will have a similar dependency ratio as the State with the highest does today, namely Tasmania. A smaller working age population needs to be offset by boosts in productivity and participation.17 FIGURE 4: FISCAL GAP PROJECTIONS OF INTERGENERATIONAL REPORTS SOURCE: Swoboda, Kai (n.d.)19 Percent of GDP 3 2 1 0 -1 -2 -3 -4 -5 -6 2002-03 2007-08 2012-13 2017-18 2022-23 2027-28 2032-33 2037-38 2042-43 2047-48 YEARS IGR1 (2002) IGR2 (2007) IGR3 (2010)

- 21. 21 future[inc] Urban population per km2 10,000 8,000 6,000 4,000 2,000 0 URBANISATION Australians are changing where they live. We will increasingly reside in capital cities – capital city populations are projected to rise by 57% by 2040.20 The New Zealand experience is even more pronounced.21 US cities are over six times denser than Australia’s. We cannot expect empty highways and high-speed trains to solve our transport woes – infrastructure can only take us so far. That means urban planning will affect Australians more than ever before. Decisions on key transport infrastructure, whether it be road or rail are already hot-button issues in State politics. Accurate Cost-Benefit Analyses (CBAs) are important at the individual project level, but the broader transport agenda around road vs. rail is more difficult to analyse. The next question on transport infrastructure is who should pay? The user-pays system of toll roads is most efficient, but traffic should be managed across the network as a whole, rather than as a series of separate transport linkages. FIGURE 5: URBAN POPULATION DENSITY, BY COUNTRY 03 SOURCE: Ellis, Luci (May 2014)22 AUSTRALIA NEW ZEALAND CANADA SWITZERLAND NORWAY SWEDEN GERMANY NETHERLANDS US ITALY BRAZIL JAPAN SPAIN CHILE FRANCE SOUTH KOREA Urban populations are defined as within cities with populations above 100,000

- 22. RISK-WISE AND A FAIR GO? A PLAN FOR AUSTRALIA’S CONTINUED PROSPERITY 22 Australians are increasingly moving into urban areas, but by global standards we dislike living near one another. Only New Zealand’s experience is close to ours among the advanced economies. Figure 5, on the previous page, shows that US cities are over six times more densely populated than Australia’s. We cannot expect empty highways and high-speed trains to solve our transport woes—infrastructure can only take us so far. The other face of increased urbanisation is the relative flight of population and businesses from the regions. There is a risk of exacerbating social issues as the urban-regional divide widens. For example, rural Victoria is four times more culturally homogeneous than Melbourne, and hence missing out on a potential ‘diversity dividend’ of the social, cultural, and economic contributions that migrant communities bring to their neighbourhoods.23 Urbanisation and an ageing population – the NZ experience Ageing growth is expected to accelerate as baby boomers begin to enter the over 65 age group. This group is expected to grow by 200,000 people between 2011 and 2021. By 2051, there are estimated to be 60 % more elderly than children. This has significant implications for policy in areas such as superannuation, health and aged care.24 There are also policy implications arising from geographical differences between areas where people reside. Over two thirds of New Zealanders live in major urban centres (86% of the population), however 22% of older people reside in secondary or minor urban areas compared to 16% of the general population.25 The 2013 census confirmed a significant shift in people from regional areas to major urban centres, especially among those of working or child bearing age. Auckland accounted for 75.8% of growth between 1997 and 2001 and is forecast to comprise 74% of national growth by 2041. Compared to urban areas, rural areas typically have a smaller population aged between 20 and 34 years. This age-geographical distribution has implications for New Zealand’s farming industry with labour shortages expected. Services, and employment in the services sector such as schools, may also come under threat.26 It is estimated 34% of small – medium enterprise owners intend leaving their businesses within the next five years, rising to 64% within 10 years.27 + Join the debate at charteredaccountantsanz.com/futureinc

- 23. 23 future[inc] THE ADVANCING TECHNOLOGY FRONTIER Robert Solow made the above statement around a quarter of a century ago, yet it applies even more powerfully today. The unprecedented rate of technological change poses more challenges and opportunities for policymakers than any of the other megatrends discussed. Just over 20 years ago, in January 1993, there were 50 World Wide Web terminals in existence. Now the internet is a central part of our everyday lives, in how we communicate, consume, do business, socialise, and govern. Some of the more recent themes in digital technology include: • businesses are increasingly going ‘mobile-first’ with their digital presence, as more digital content is consumed through smartphones and other mobile devices – this can be either through apps or dedicated websites; • cloud-based computing means more information is being shared and centrally located than ever before; • the cloud combined with mobile and internet technologies are allowing small and medium sized businesses the ability to both cut costs and better engage customers, thereby lowering barriers to enter new markets; • harnessing data as part of everyday business, where data can be collected and analysed by digital technologies, then patterns and relationships can be found through the volume of observations that are available to be analysed at once; and • information technology spreading into other parts of our lives, where smart technology is being embedded around the house and the built environment, for example in our electricity and transport networks. On an individual basis, Australians are early adopters of new technology. In 2013 smartphone penetration in Australia was 65% of the population, among the world’s highest.28 Australian businesses are slower to move than businesses in other parts of the world, but new technologies are forcing their hand. A third of Australian industries face the ‘big bang’ scenario of major disruption within the next three years from these technologies.29 Technological change will create winners and losers in business, but will have even greater implications for people in the workforce. Some 47% of US jobs are at risk of being automated over the next 20 years.30 Besides helping workers displaced by technology to reskill and stay in the labour force, governments need to help foster those technologies which have greater social benefits and assist productivity growth. Developments in technology will interact with the themes discussed in this paper: • improving access to Asian markets for Australian businesses, and vice-versa but it will also increase competition; • enabling the productivity gains required to offset the reduced productive capacity from the ageing population, and enable participation of young parents and semi-retired; and • helping cities to work more efficiently and help address disparities between urban and regional areas. Importantly, technology will be a key consideration in the discussion of social equity into future. “WE SEE COMPUTERS EVERYWHERE except in the productivity statistics.” Robert Solow, Nobel Laureate 04

- 24. RISK WHERE ARE THE POLICY CHALLENGES? WHERE IS RISK MANAGEMENT HEADING? 01 02

- 25. 25 future[inc] Risk is a pervasive feature of our lives and yet it rarely features as a standalone theme in public debate. The megatrends highlight the fast pace of change in many aspects of our lives, which creates and amplifies risks for governments and people. The Asian century and global economic integration are changing the macroeconomic landscape, and exposing people to greater uncertainty in the labour market. Digital networks are now critically important for governments, businesses, and people. The ageing population and government retirement policies mean more people face greater financial risks in funding their retirement. The risk-taking behaviour associated with the GFC has dominated the airspace in recent times. While there are clear policy lessons from that episode, there is a need for a separate public conversation about risk. The issue is twofold: • the megatrends in Australia are making risk a challenge in new parts of our economy and society, and a greater issue in others; and • attitudes to risk need to evolve from risk avoidance to risk management. Not all risks can be eliminated or even reduced, and efforts to avoid them can be more costly than the negative outcome itself. Similarly, people may believe that risk has been avoided when it has just been transferred to another party. For example, insuring against natural disaster risk doesn’t eliminate it; it simply shifts the risk (or most of it) to the insurer or guarantor. Narrow measures aimed at avoiding these types of risk are not only futile but can be detrimental to fostering a vibrant, dynamic economy. The consequences of maintaining the current (or historical) attitudes to risk are significant. On the downside, there are indications that risk mismanagement is hampering productivity growth. On the upside, better risk allocation and awareness will foster productivity. Individuals, businesses and policy-makers should seek to be ‘risk-wise’, as opposed to risk-averse or risk-seeking. For more insights go to + charteredaccountantsanz.com/futureinc

- 26. RISK-WISE AND A FAIR GO? A PLAN FOR AUSTRALIA’S CONTINUED PROSPERITY 26 WHERE ARE THE POLICY CHALLENGES? THE INCREASINGLY SYSTEMIC NATURE OF RISK The megatrends of digital technology and the Asian century make digital, financial and economic systems more interdependent. As we saw in the GFC, this increased interdependence makes risks more systemic than in the past. The World Economic Forum released the ninth edition of its global risk perceptions for 2014, including a risk interactions map, which shows how global economic, environmental, geopolitical, societal and technological risks could potentially interact. It is important to conceptualise how risks from different peripheral areas can compound to cause political, financial and/ or social instability; it is also useful to see all manner of risks represented in one place. The method of stress-testing banks, which has been implemented around the world as part of the new Basel III regulations, is one example of efforts to better understand systemic risk. Those risks which are less systemic can be successfully managed through aggregation – the key is to identify which parts of risk are genuinely diversifiable and which are not. 01 FIGURE 6: GLOBAL RISKS 2014 INTERCONNECTIONS MAP SOURCE: World Economic Forum (2014)31 Number and strength of connections (weighted degree) ECONOMIC RISKS GEOPOLITICAL RISKS TECHNOLOGICAL RISKS SOCIETAL RISKS ENVIRONMENTAL RISKS Data fraud/theft Failure of financial mechanism or institution Unemployment and underemployment Organised crime and illicit trade Political and social instability Global governance failure Extreme weather events Weapons of mass destruction Critical information infrastructure breakdown Biodiversity loss and ecosystem collapse Antibiotic-resistant bacteria Natural catastrophes Man-made environmental catastrophes Liquidity crises Oil price shock Decline of importance of US dollar ice shock Fiscal crises State collapse Income disparity Cyber attacks Corruption Mismanaged Chronic diseases urbanisation Failure of critical infrastructure Climate change Water crises Food crisis Interstate conflict Economic and resource nationalisation Pandemic Terrorist attack

- 27. 27 future[inc] IDENTIFYING RISKS IN THE MACROECONOMY Besides national security, the largest scale risk-management effort is sustaining economic growth. The set of financial regulation agencies have this as a key mandate. There is little doubt that active monitoring and management of the economy is a worthwhile endeavour. The most difficult part of that job is predicting the source of the next adverse shock to the economy. Where will the next recession start? Public consensus is that the next shock will come from overseas, most likely in the form a sudden contraction of demand from our Asian trading partners. Significant credit events in Europe are also not out of the question; but with the Basel III measures applied by governments around the world, this issue is being addressed. International policy directives on systemic risk, such as Basel III, have been a focus of the G20 meetings in Australia this year.32 Domestic regulators are in some senses the victim of their own success – their role in Australia’s 23 years of continuous economic growth leads many to presume that the Australian economy cannot create the next mess on its own. Yet there are reasons to believe the opposite is true – for example, our flexible exchange rate means an external demand shock, while not pleasant, wouldn’t be as calamitous as a severe ‘correction’ in domestic asset prices, specifically housing. Some of the megatrends discussed earlier, particularly the ageing population and increased urbanisation, will serve to compound such an event. This is an area of active policy discussion—from the FSI to the latest commentary from the RBA on measures to contain housing price growth.33 The key point is that we need to remain alert to the internal and external stressors of the Australian economy. FROM RISK AVOIDANCE TO RISK MANAGEMENT What is the harm in avoiding risk? If the primary aim is to avoid risk, this can lead to distortions in behaviour and the economic consequences can be considerable. The RBA Deputy Governor Phil Lowe discussed how risk interacts with the concepts of innovation, productivity and demographic change: “In my opinion, it is appropriate occasionally to ask whether we have got the balance right. Reducing risks is not always cost free – resources need to be devoted to the task and this means that these resources cannot be used for other tasks. And perhaps even more importantly, it might also be the case that a more risk-averse society is naturally less inclined to support and finance innovation, toimplementnewprocessesandtoapplynew technologies. If this is indeed the case, it has implicationsforfutureproductivitygrowth.” Phil Lowe, RBA deputy governor, Speech to The Sydney Institute, Sydney –12 March 2014

- 28. RISK-WISE AND A FAIR GO? A PLAN FOR AUSTRALIA’S CONTINUED PROSPERITY 28 The balance that Dr. Lowe refers to is between the risk-seeking behaviour witnessed in the lead-up to the GFC, and the compliance-paralysis caused by red tape instituted by both business and government. The case for policy action was made clear with the events between 2000 and 2010 including the collapses of Enron and WorldCom and the GFC. These examples also reinforced the benefits of prudent regulation in Australia relative to other parts of the world. However, the increased level of regulation has led to a situation where compliance dominates responsible strategy. Businesses are more focussed on following the regulatory traffic lights, rather than taking the best possible route. At an economy-wide level, these regulations can be very costly. The process of making and following rules costs Australia over $250 billion each year, with two-thirds of this burden coming from the private sector34. Specific examples are not difficult to find: over 45% of costs in electricity networks are due to growth in peak demand.35 Hence regulations that ensure electricity outages are limited to, say, four minutes per year rather than five would involve significant cost per consumer. Until recently, these reliability standards have been set with limited regard for their economy-wide cost. The process of making and following rules costs Australia over $250 billion each year, with two-thirds of this burden coming from the private sector. There is no such thing as riskless innovation or entrepreneurship – some level of risk needs to be tolerated, and even encouraged. As the Austrian economist Josef Schumpeter described it, the ‘creative destruction’ within a vibrant economy is inherently risky for participants. But, it is a key ingredient, and must be managed. The management task should be undertaken by those who can do it most effectively. ROLES FOR INSURANCE MARKETS AND GOVERNMENTS IN RISK MANAGEMENT Managing an adverse or negative risk is a threefold task: • measuring and monitoring: risks need to be quantified frequently to design and implement an appropriate response; • active minimisation: taking steps to reduce the overall uncertainty where it is beneficial to do so; and • resilience and mitigation: planning for the event of an adverse outcome to mitigate the impact. As the Austrian economist Josef Schumpeter described it, the ‘CREATIVE DESTRUCTION’ WITHIN A VIBRANT ECONOMY IS INHERENTLY RISKY for participants. But, it is a key ingredient, and must be managed.

- 29. 29 future[inc] FIGURE 7: PRINCIPLES FOR ALLOCATING (INSURABLE) RISK It is a complex task, but one that we do in our everyday lives. There is a natural tension between centralising risks, where risks can be pooled, and more resources can be devoted to the measurement and mitigation, and localising risks with those parties who are able to most directly observe them and take steps to manage them. Allocating risk to those who are best placed to bear it is the most efficient outcome. Where risks are insurable, there is a good argument to develop a market for insurance, which generally will allocate risk effectively between insurers, governments, businesses and individuals. Figure 7 above shows the how the market for insurable risk allocates it in an effective manner. A number of issues remain with an insurance-based approach to managing risk: • moral hazard of insurance; • government’s role as an insurer of last resort; and • affordability and underinsurance. These issues span the full spectrum of risk as outlined in the figure above, and are also affected by the megatrends. In the financial services context the moral hazard and implicit insurance of banks that are ‘too big to fail’ falls within the scope of the FSI and are current topics of public debate. The best ways to manage natural disaster risk, whether through formal insurance or otherwise, are the topic of a current Productivity Commission inquiry. SOURCE: Insurance Council of Australia (2014)36 • Risk is allocated and pooled within the economy • Risk is allocated towards those best placed to manage it • The market provides price signals to encourage an efficient allocation of risk INSURERS GOVERNMENT BUSINESS INDIVIDUAL SPECTRUM OF RISK Disaster Financial Individual income Life/health Home/property Motor vehicle Travel

- 30. RISK-WISE AND A FAIR GO? A PLAN FOR AUSTRALIA’S CONTINUED PROSPERITY 30 This is a change from 10 or 20 years ago, when the risk of retirement was more largely borne by government through pensions and defined benefit schemes. Given their role to potentially fill the gap, the incentive for governments is to educate people about how risks work in investment, and how longevity risks can be better understood, if not reduced. The ageing population, combined with the self-managed superannuation model, means decisions over a large part of Australia’s accumulated wealth are made by non-professional investors. Strategies to reduce people’s reliance on the pension safety net, such as taking retirement savings as an income stream rather than a lump sum, may be a more efficient allocation of risk and so should be considered. Beyond education and financial literacy, the complexity of managing individual finances shows the increasing need for professional advice. Shortcomings in the current regulation of financial advice have been revealed, leading to policy reform of the sector. Ensuring any advice provided is in the best interests of consumers will increase confidence, and allow better informed management of retirement and superannuation risk. The decisions about funding retirement beyond superannuation guarantees should be left to individuals but governments need to ensure that people have the capacity to make good decisions. Governments also have responsibility to regulate the sector, given the compulsory superannuation contribution system. New digital technologies are breaking down barriers to entry to selling insurance, and are also improving the accuracy of risk-based pricing. Improved risk-based pricing can lead to fewer cross-subsidies between low-risk and high-risk individuals. In some cases, this may price high-risk individuals out of the market. This may be an issue for policymakers where reduced affordability results in underinsurance. Ultimately, the government is in a unique position to bear risk but cannot manage risk very well relative to an ideal market-based outcome, where decisions can be decentralised and well-informed. However, using markets to manage risk has its limitations: where people have little information, or where insurance markets cannot be effectively regulated, privatisation may not be the answer. In any case, the upfront fiscal benefits of the privatisation of risk management should not be the primary concern. In any case, the upfront fiscal benefits of privatisation of risk management should not be the primary concern. RISK ATTITUDES AND PRACTICES IN WEALTH MANAGEMENT Risk is an integral part of wealth accumulation and management. The business of the finance industry is to understand and exploit these risks. The ageing population, combined with the self-managed superannuation model, means decisions over a large part of Australia’s accumulated wealth are made by non-professional investors.

- 31. 31 future[inc] As research and technology improves our understanding of these natural hazards, and the best measures that can be taken, the case for proactive investment in disaster mitigation is growing: a $250m investment on an annual basis has the potential to cut natural disaster costs by 50% by 2050, which are projected to grow to $23 billion each year by that time.38 Prevention is clearly better than cure in terms of efficient and effective natural disaster risk management. How should the government response to the inevitable occurrence of natural disasters be funded? While government’s role in managing catastrophic risk is clear, the funding of this risk can be more efficiently and fairly targeted to those exposed, rather than a long-term implicit subsidy between individuals with different levels of exposure. This is particularly relevant for bushfire risk where return periods are generally shorter, and where certain people have much higher exposure than others. Rather than ex-post funding of natural disasters, it is best to spread the cost before and after the event. The New Zealand Earthquake commission model does this by requiring exposed individuals to contribute on an ongoing basis through insurance premiums. The Victorian Government has recently changed its fire services levy to be based on land rates and geographic region, rather than insurance premium.39 This more equitably funds the government’s role as the insurer of last resort, as opposed to levying all taxpayers. MANAGING NATURAL DISASTER RISK The Australian natural environment is savage. Whether it is drought, bushfire, flood, or cyclone, Australia gets more than its fair share of environmental disasters and disruptions. Australians have been coping with natural disaster since long before European settlement. The evidence from the latest Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) synthesis report shows that it is likely these extreme weather hazards have grown in frequency and/or severity in recent decades, as a result of human influence37. At the same time, increased built infrastructure in hazard-prone areas increases the value at risk to natural disaster. Australians spend $1 in pre-disaster resilience and mitigation for every $10 that is spent on post-disaster response. What are the right types of policy measures to deal with disaster risk – adaptation, mitigation, resilience, or response? In 2013 the IAG business roundtable for Disaster Resilience and Safer Communities released a report showing that Australians spend $1 in pre-disaster resilience and mitigation for every $10 that is spent on post-disaster response. Spark your interest at + charteredaccountantsanz.com/futureinc

- 32. RISK-WISE AND A FAIR GO? A PLAN FOR AUSTRALIA’S CONTINUED PROSPERITY 32 Bringing risk-based thinking into policy and individual decision-making: • The megatrends affecting Australia in coming years will impose new and greater risks on the economy and individuals; whether they be labour market risks, retirement risks, or natural disaster risks, we need to ensure Australians are capable of managing these effectively. • Rules and regulations set to minimise risk, rather than mange it, collectively impose a large burden on the economy. The process of making and following rules costs Australia over $250 billion each year. • In general, risk should be borne by those who can best manage it, rather than who can afford it, or who would be most vulnerable (though one party might be all three of these). • Generally, proactive steps are better than reactive ones – action (not just planning) ahead of the event is usually a more effective and efficient use of resources. • Risk management itself isn’t the end game – the resources allocated to managing risk, whether it be by individuals, policymakers or business, should be commensurate with the expected gains or losses avoided. WHERE IS RISK MANAGEMENT HEADING? At the policy level, a number of reform proposals will come from the Future of Financial Advice and FSI reviews, which are due to be finalised at the end of the year. Both enquiries received a large number of submissions from the business community, including from Chartered Accountants Australia and New Zealand. Besides these more strategic policy decisions, there are specific policy actions which are targeted at altering people’s behaviour, and also simple business strategies separate from policy that can help limit the burden of risk management. STRATEGIES TO ENABLE PEOPLE TO BETTER MANAGE RISK Both natural disaster and financial risks warrant coordinated, proactive steps from government and individuals. If policymakers get it wrong, the political system provides a level of accountability. Individuals facing tail risks – those that severely affect a small share of people exposed – are inclined to take a ‘head in the sand’ approach. These individuals appear not to understand the risks very well, including their own exposure. Rather than greater risk exposure, the solution is to increase risk understanding, through education. By enabling people to undertake an achievable level of risk management, the task of centralised risk management can be significantly reduced. 02

- 33. AUSTRALIA: LAND OF THE FAIR GO?

- 34. RISK-WISE AND A FAIR GO? A PLAN FOR AUSTRALIA’S CONTINUED PROSPERITY 34 The trends identified so far point to inevitable changes to the policy landscape into the future. Globalisation, technological change and an ageing population all have the potential to change market outcomes and the distribution of wealth through the economy. Change is not to be resisted; indeed, there are many opportunities to be grasped from rapidly increasing technological and geographical linkages with the rest of the world. But rapid change can leave some people behind. Inequality has been increasing over time in almost all countries for which reliable data are available. In some parts of the world this is starting to damage social cohesion, a cost which cannot be captured in GDP or measures of income dispersion. As noted in an IMF working paper: “inequality can undermine progress in health and education, cause investment-reducing political and economic instability, and undercut the social consensus required to adjust in the face of shocks, and thus it tends toreducethe pace and durability of growth.40” While Australia is not at this point, however, earning disparities have been increasing over time. The concern is that this may be due, at least in part, to disadvantaged groups not having the same opportunities to participate in the nation’s continued prosperity as other groups. If we are to maintain our image as the ‘land of the fair go’, policy needs to ensure that vulnerable people do not get left behind. Structural change on a large scale is not a new phenomenon. The microeconomic reforms in the 1990s significantly altered the economy and led to large net gains, while at the same time causing disruption to many industries and their workers whose skills were no longer valued in the new environment. On a wider scale, the forces of globalisation have had similar effects. Economists have largely welcomed the impacts of globalisation in opening up new markets to trade, thereby allowing less developed countries to participate in the world economy. Rapid growth in these countries has tended to reduce inequality at the country level as the developing world has caught up with the West. But not everyone has been a winner, and while income inequality has fallen across countries, inequality within countries has tended to become more pronounced. Low-skilled workers in developed countries have faced increasing competition from labour in the developing world and this has placed downward pressure on their wages. Likewise, workers in developing countries have not all gained from the spoils, as only those with sufficient skills and education have been able to participate in the new global industries.

- 35. 35 future[inc] Varying levels of access to technology has driven ‘digital inequality’, which has also tended to benefit relatively highly-skilled workers who have been able to take advantage of innovation. Indeed, the IMF found that technological progress has a greater impact than globalisation on inequality within countries, particularly developing countries, as shown in Figure 8. Developing Asia has a greater spread of ICT adoption and a closer correlation between ICT and inequality. But even in developed countries greater ICT adoption is associated with higher inequality. Overall, it has been the low skilled, more vulnerable workers, in each set of countries who have gained least from growth, while those with skills and access to technology have moved ahead. This hollowing out of the middle class across the globe led the World Economic Forum to declare inequality as the biggest threat the world currently faces and the risk ‘most likely to cause serious damage globally in the coming decade’.42 Overall, it has been the low skilled, more vulnerable workers who have gained least from growth, while those with skills and access to technology have moved ahead. FIGURE 8: INEQUALITY AND TECHNOLOGY SOURCE: IMF (October 2007)41 ADVANCED ECONOMICS Residual inequality 0.3 0.2 0.1 0 -0.1 -0.2 -0.3 -3 -2 -1 0 1 2 3 ICT CAPITAL (percent of total capital stock) DEVELOPING ASIA Residual inequality 0.3 0.2 0.1 0 -0.1 -0.2 -0.3 -3 -2 -1 0 1 2 3 ICT CAPITAL (percent of total capital stock)

- 36. RISK-WISE AND A FAIR GO? A PLAN FOR AUSTRALIA’S CONTINUED PROSPERITY 36 EQUITY AND INCLUSIVE GROWTH Is addressing inequality harmful to economic growth? Given that raising taxes and redistributing the proceeds through cash transfers imposes inefficiencies, the equity versus growth debate has often been framed as one of a trade-off: greater equity can only be achieved at the expense of GDP. More recently, this conventional wisdom has been questioned as strong growth in developing countries has not tended to reduce inequality. Research is increasingly finding that causality may run the other way: higher inequality may cause lower growth. For example, a recent Standard and Poors report claimed: “[Large] income imbalances tend to dampen social mobility and produce a less-educated workforce that can’t compete in a changing global economy. This diminishes future income prospects and potential long-term growth, becoming entrenched as political repercussions extend the problems.”43 This thinking has led to a shift towards a focus on ‘inclusive growth’; growth that raises both GDP and the incomes of all members of society along with it. The World Bank, OECD and IMF have increasingly focussed on win-win economic reforms that obtain the dual goals of raising both equity and growth. Such reforms can broadly be classified as those which increase access or participation into the health and education systems and the workforce by low-income and disadvantaged members of society. That is, they can loosely be labelled as those policies which promote equality of opportunity. What do we mean by equality? Targeting the ‘right’ level of equality is difficult. Few would argue that a completely uniform distribution of wealth is desirable or even achievable, in part because of the costs of doing so but also because inequality in earnings can reflect legitimate decisions around individuals’ labour-leisure trade-off. What level of equality should we target, and how would we know when we got there? Commentators often distinguish between two notions of equality: • Equality of opportunity – the notion that all people should have access to the same opportunities regardless of their position at birth; and • Equality of outcomes – the realised distribution of incomes (or other welfare metrics). Equality of opportunity is usually supported as the desirable target for policy. It embodies the Australian concept of a ‘fair go’—the idea that individuals should not be in some way pre-destined to lead a certain way of life simply because of the wealth of the family or neighbourhood they were born into. Achieving equality of opportunity not only helps those who are most disadvantaged, it also grows the size of the ‘economic pie’ by improving education and employment outcomes. Equality of opportunity is best achieved by promoting participation in activities that are keys to positive economic outcomes, in particular education and employment. Equality of outcomes on the other hand is achieved through policies that ‘even out’ realised differences in incomes. This is achieved primarily through the transfer system where a progressive tax system funds payments to low-income individuals.

- 37. 37 future[inc] Join the debate at + charteredaccountantsanz.com/futureinc The lexicon of inclusive growth has begun to find its way into political discussions. A recent G20 Labour and Employment Ministers statement noted that: “promoting and creating quality jobs, and tackling the economic and social consequences of unemployment, underemployment, inequality and social exclusion, areprioritiesforalloureconomies”44 Equality of opportunity and equality of outcomes can be thought of, respectively, as prevention and cure. Equality of opportunity can lead to inclusive growth and therefore less disparity of outcomes (it helps prevent inequity). With equality of opportunity in place, market outcomes can be better relied upon to distribute income according to the value of people’s output. However, if some groups do not have opportunities or circumstances prevent people from taking up opportunities, so that not everyone can benefit from economic growth, equity policies can provide the safety nets for those who fall through the gaps. Equality of opportunity and equality of outcomescanbethoughtofaspreventionand cure. Increasing equality of opportunity can lead to inclusive growth and therefore less disparity of outcomes: it helps prevent inequity. INEQUALITY IN AUSTRALIA Using broad measures of income inequality, Australia performs close to the average of the developed world. The Gini coefficient is the most commonly used single measure of inequality. It takes a value of 0 for a society where income is perfectly evenly distributed, and 1 where all income accrues to only a single individual. The closer the value is to 1, the less equal the distribution of wealth. Before taxes and transfers, Australia’s Gini coefficient is 0.46, slightly below the OECD average. After taxes and corresponding transfers between members of society the coefficient falls to 0.32, around the OECD average again but above the Nordic countries which have values between 0.25 – 0.27. Figure 9 provides a summary of Australia’s performance against other OECD countries against several common measures of inequality.

- 38. RISK-WISE AND A FAIR GO? A PLAN FOR AUSTRALIA’S CONTINUED PROSPERITY 38 AUSTRALIA NEW ZEALAND UK US NORWAY OECD Gini (pre-transfers) 0.46 0.45 0.53 0.51 0.42 0.47 Gini (disposable income) 0.32 0.32 0.34 0.39 0.25 0.32 P90/P10* 4.4 4.2 4.0 6.2 3.0 4.4 Relative poverty rate** 14% 10% 10% 17% 8% 12% * The ratio of disposable income of the top 10% of income earners to those in the bottom 10%. ** The proportion of individuals with disposable income less than 50% of the median. FIGURE 9: SUMMARY MEASURES OF INEQUALITY FOR AUSTRALIA AND OTHER OECD COUNTRIES These measures have tended to show a rise in the dispersion of disposable incomes over time in Australia. This has its source in both labour market and policy outcomes. On the labour side, the continuous growth of the economy over the past quarter century has seen wages increase at a faster rate for higher income earners than for those at the bottom of the income band. Low-income people have benefited in absolute terms from economic growth but have received a much smaller share of the spoils. Low-incomepeoplehavebenefitedinabsolute terms from economic growth but have received a much smaller share of the spoils. While increased incomes to those at the top could have facilitated increased transfers, various policy changes have meant the reverse has occurred. Successive reductions in the marginal tax rate at the top of the income band (from 60% in 1981 to 45% currently), and a general reduction in the progressivity of the tax system has reduced the redistributive power of taxation (Figure 10). At the same time, allowances have fallen in relative value as they have been indexed against CPI, which has grown at a slower rate than average wages. SOURCE: OECD StatExtracts (2014)45

- 39. 39 future[inc] For more insights go to + charteredaccountantsanz.com/futureinc FIGURE 10: REDISTRIBUTIVE POWER OF TAXATION OVER TIME The story in New Zealand has been similar. Inequality rose dramatically in the late 1980s to mid-1990s, the second largest rise in all OECD countries. As with Australia, this has been driven by a combination of market and policy outcomes. Labour incomes of the wealthiest decile rose at more than twice the rate of the poorest 10%, while at the same time the tax share fell for those at the top, with marginal tax rates falling from 60% in 1980 to 33% by 2010. Since 2000, inequality of disposable incomes has remained largely unchanged despite the dispersion of market incomes narrowing, indicating that the equalising effects of government transfers have achieved less over this period. In Australia there are clear differences in earnings across different groups: those aged 65+ are around four times more likely to be in a position of relative poverty than those in the 18 – 25 bracket (33% and 8% respectively). There is also a marked difference between genders, with female ordinary time earnings around 18% lower than for males. The Productivity Commission estimated that in 2009 around 25% of the Gini coefficient could be attributed to the gender gap.47 SOURCE: Productivity Commission, March 201346 AVERAGE TAX RATE BY EARNINGS DECILE (10 = highest earnings) 40% 30% 20% 10% 0% 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 1988 – 89 1993 – 94 1998 – 99 2003 – 04 2009 – 10 CORRECTION TO GINI COEFFICIENT THROUGH TAXES AND TRANSFERS 0.5 0.045 0.4 0.035 0.03 1988 – 89 1993 – 94 1998 – 99 2003 – 04 2009 –10 YEARS

- 40. RISK-WISE AND A FAIR GO? A PLAN FOR AUSTRALIA’S CONTINUED PROSPERITY 40 EQUALITY OF OPPORTUNITY The discussion so far has focussed on realised distributions of income across society, that is, equality of outcomes. While equality of opportunity is the focus of policy, it tends to be harder to measure. One way of doing so is to look at the correlation of incomes between parents and children: if all children have equal opportunities regardless of the family or neighbourhood they are born in to, we would expect this correlation to be low. Research indicates that this is the case, with around 17% of children born into the highest earnings quintile ending up in the lowest, and 12% of those in the lowest moving into the top quintile.48 This degree of social mobility ranks close to the top of the OECD. Overall, Australia experiences levels of inequality similar to the average of the developed world and this has tended to rise in recent years. Behind this is a mixture of structural changes in the labour market which have tended to see gains accrue relatively more to the wealthy than lower income individuals, as well as policies which have gradually reduced the redistribution of income throughout society. While the relatively high levels of social mobility indicate the notion of a ‘fair go’ is still relevant, a lack of action to address rising inequality and declining participation among the most vulnerable members of society could see an Australia where this no longer can be taken for granted. POLICIES TO INCREASE EQUALITY OF OPPORTUNITY The bipartisan support for the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS) shows that there can be significant public support for programs which assist the most vulnerable members of society, even if it means a direct increase in taxes. Such reforms can be expected to deliver economic benefits and hence need not be interpreted as welfare. In the case of the NDIS, policy is achieving the dual goal of encouraging disabled individuals and their carers back into the workforce and reengaging these individuals with society. The Closing the Gap program represents another example of how increasing the participation of isolated members of society can achieve dual objectives of growth and equity. While this is still in its early stages and some elements of the program have not progressed, other elements are beginning to see some results. The benefits from achieving the goals are significant. Closing the gap between indigenous health and employment outcomes with those of the general population could yield net economic gains of $24 billion a year by 2031.49

- 41. 41 future[inc] Education is a key area where public investment can result in both social and economic dividends. Studies of equity typically place particular emphasis on the importance of early childhood education and care (ECEC) which has been shown to significantly improve student progress throughout the entirety of a child’s schooling life. These effects are likely to be more significant for students from disadvantaged backgrounds. In one study the impact on student outcomes of a 10 percentage point increase in free ECEC places for three-year-olds has been shown to increase literacy levels by twice the level for children from disadvantaged neighbourhoods compared to all children.50 Yet this does not overcome the educational challenges that disadvantaged children have over higher socio-economic status (SES) peers. Figure 11 shows that for UK children with equal scores at 22 months, those from a low SES background will perform worse over time than those from higher SES backgrounds. It appears that parental income may matter more in child development than the ability of the child. CLOSING THE GAP BETWEEN INDIGENOUS HEALTH AND EMPLOYMENT OUTCOMES with those of the general population could yield net economic gains of $24 billion a year by 2031. FIGURE 11: PERFORMANCE IN ECEC BY SES CATEGORY AND INITIAL STARTING POSITION Average cognitive test score 100 80 60 40 20 0 0 20 40 60 80 100 120 AGE IN MONTHS High SES, High Q Low SES, High Q High SES, Low Q Low SES, Low Q SOURCE: Feinstein, Leon (2003)51

- 42. RISK-WISE AND A FAIR GO? A PLAN FOR AUSTRALIA’S CONTINUED PROSPERITY 42 In Australia, children from Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander and non-English speaking backgrounds, children with a disability, children in low SES families, and children who live in rural and remote areas are all under-represented in early childhood programs.52 Increasing participation for these groups has the dual benefits of improving education outcomes for the most disadvantaged, while increasing the labour force participation of their parents. Low-income families are also more responsive to ECEC price increases as the opportunity cost of reducing work hours to care for a child is lower. Recent reforms under the National Quality Framework in early childhood education have helped to improve the quality of education, but have also increased ECEC prices through the increased costs they impose on providers. DIGITAL DIVIDE Access to technology in education will be important in addressing the digital divide in Australia and ensure that digital literacy develops early in life. The ABS’ most recent Household Use of Information Technology survey indicates that households with annual income less than $40,000 are around four times more likely to be without the internet than those earning $40,000 – $80,000, and around eight times more likely than those earning more than $80,000.53 Access to technology at schools is crucial in breaking this divide, but will require ongoing committed funding if it is to be achieved nationwide. Households with annual income less than $40,000 are around four times more likely to be without the internet than those earning $40,000 – $80,000, and around eight times more likely than those earning more than $80,000. While policies that promote equality of opportunity have the potential for double dividend outcomes of increasing both growth and equity, safety nets in the form of cash transfers to low income households will need to form part of any strategy to address equity. These, along with significant reforms to areas such as health or education, will require a sustainable fiscal environment. The upcoming tax White Paper provides an opportunity to address structural issues with the tax base. While policies that promote equality of opportunity have the potential for double dividend outcomes of increasing both growth and equity, SAFETY NETS IN THE FORM OF CASH TRANSFERS TO LOW INCOME HOUSEHOLDS WILL NEED TO FORM PART OF ANY STRATEGY TO ADDRESS EQUITY.