The Slashdot Effect. A site owner’s biggest dream; and their worst nightmare. In the late 90’s, community site Slashdot had a such a massive and loyal following, that any link from their site resulted in a surge of traffic that struck like lightning. If your site was posted to Slashdot, and your servers were in earshot, you’d hear them whirring under the pressure, trying to keep up with hundreds or thousands of people coming to the site in minutes. Properly harnessed, it could signal a major turning point in the popularity of a site. Mismanaged, and it would be nothing more than a bad day.

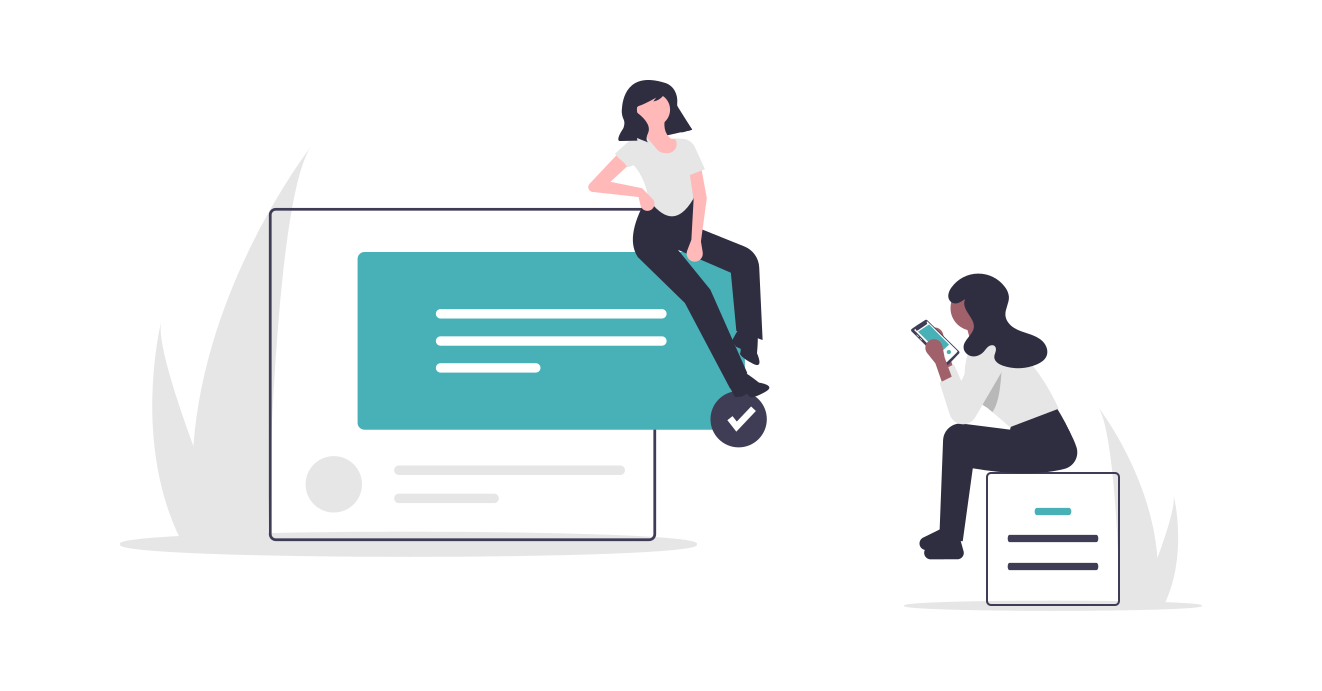

Slashdot began as the proto-blog of programmer and open source advocate Rob Malda. It was originally called “Chips & Dips,” but in 1997, Malda changed the name to Slashdot, a play on just how difficult that is to say out loud (say http://slashdot.com out loud and you may just get the joke). It’s tagline was simple, “News for Nerds. Stuff that Matters.”

Malda began by simply posting links and commentary, mostly tech or development related news. But in his blog’s Slashdot incarnation, he inverted the site’s function, opening up link submissions to a wider group of contributors and emphasizing the site’s threaded comments in its design. Slashdot’s inner circle of link curators would post new links, multiple times a day, and open them up for discussion.

It’s openness as a foundational principle led to its popularity. Links posted to the site were often followed by hundreds of comments, threaded into neat forks and sections. The web, at time, was still populated by mostly tech aficionados and Slashdot became a kind of sanctuary for the computer geek power user. Within a year, the site was being visited 100,000 times a day.

It became so popular that by 1998, the Slashdot Effect had become a well-known phonemonen. Sites were posted to Slashdot for basically any reason — a nifty design or a handy article — and there was no way to know when it might happen. But when it did, thousands of Slashdot users could flood your site all at once. Servers at the time were not built for that many simultaneous users. If you weren’t operating a sophisticated setup, it was more than enough to take your site down.

Among Slashdot insiders, it was known simply as “/.”, used as a verb, as in: “I heard your site slashdotted, I hope it survived.” Server administrators wrote detailed tutorials about how to configure your site to handle the load from Slashdot. And savvy site owners figured out ways to capture the ephemeral effect and keep people coming back to their sites even after the wave of Slashdot visitors had subsided.

While plenty of site’s sought to capitalize on the effects of Slashdot, it would be several years before other sites (Digg, Reddit) would try and recreate it. There was, however, one relatively early attempt from a group of webzine creators wanting to take their editorial vision to new heights.

The late 90’s also saw a period of media consolidation as industry standards began to move their publications online. The more amateur upstarts, online-only publications known as webzines, found it more and more difficult to compete.

Two of the more popular zines, Feed and Suck, decided to work together to try and compete with the opposition. They created a new unified company in July of 2000 known as Automatic Media. Before that, they had both been run as independent operations, Feed from New York and Suck in San Francisco. Together, they had had a massive influence on the early web, defining a style and tone that has persisted to this day. Banding together brought distinct advantages, allowing them to pool together editorial resources and provide greater reach to advertisers.

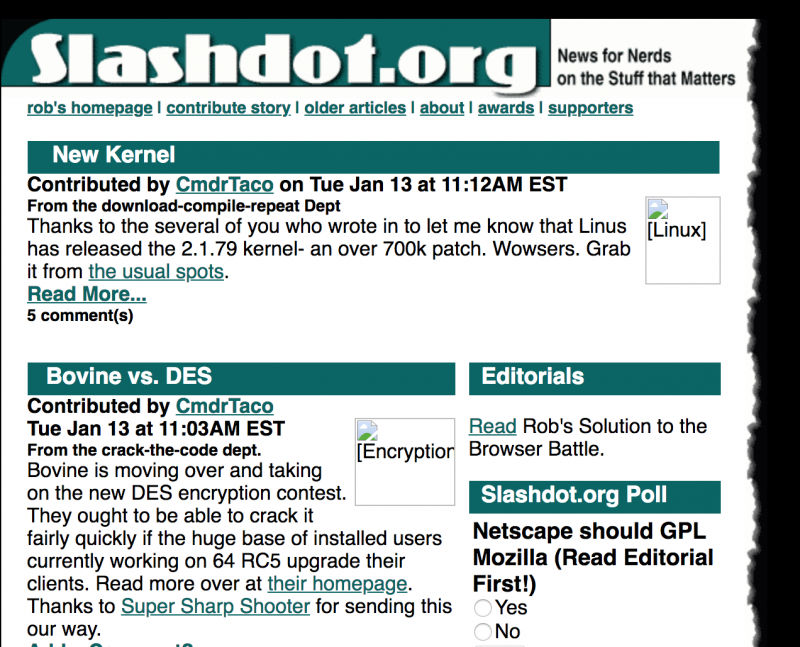

Their first joint venture got started shortly after the company formed. It was known internally as an evolution of Slashdot, using the same model but with a pop-culture slant, broader appeal, and tighter editorial curation. A way to capitalize on the Slashdot effect with an even greater audience. Pop culture, after all, had a wider reaching audience than the tech-focused Slashdot. And Automatic Media had a unique ability to recruit the trendiest writers and content partners to whatever they were building.

The site, which would eventually be called Plastic.com, was spearheaded by Joey Anuff, one of the original creators of Suck. Anuff imagined an upgraded version of Slashdot (in fact, they even used Slashdot’s codebase and CMS, known as Slash, which Malda had open sourced, true to his site’s philosophical roots). He reached out to a dozen or so small zines and content creators. The idea was, Plastic.com would feature content from these partners most prominently, and in return editors and writers from the affiliated publications would add their own editorial and commentary to the site. Anuff had gotten buy-in from magazines like Spin, New Republic, and Wired, combined with more niche outlets.

Some of the writers and editors for Automatic Media began to speak publicly about their site. They saw it as a natural outgrowth of what they had already been working on, but a way to invite their readers into the writing. The first generation of webzines had been largely broadcast out. But from emails and comments they knew that their readers craved deeper conversations. Plastic.com would give them that platform, and make their content interactive by default.

Plastic.com launched on January 15, 2001, six months after Automatic Media was formed with a staff of only 4, including Anuff.

For a small, experimental operation, it had some success from webzine loyalists willing to give it a try. It’s merging of tech and editorial vision drew a lot of attention from the press, and the partners it launched with out of the gate kept it filled with quality content. They used a sophisticated karma system derived from Slashdot to reward users for coming back and keeping conversations going. It didn’t start a revolution, but it was only ever meant to be version 1.0. Lots of users kept coming back day after day, week after week. Besides, the team had a lot more plans for it.

It could not have come at a worse time. Suck contributor Tim Cavanaugh would later say, “it was the most ill-timed event in the history of man.”

The site was beset with issues from the beginning, both technical and strategic. It was itself often slow to load, strained by a server traffic in a strange reversal of the Slashdot effect. Content partners, too, were disappointed in the numbers Plastic.com was able to bring to their sites. It seems that most users chose to simply remain on Plastic.com engaged in the long-winded comment threads, bypassing the link entirely and doing nothing for the partner expecting to be slashdotted. It’s largest issue, however, was financial.

Other sites had fared in far worse conditions. The hype of the dot-com boom meant that even the worst ideas survived, even thrived. Plastic.com wasn’t a bad idea. In fact, it was a good idea. It was, as Cavanaugh noted, a matter of poor timing more than anything else.

The development Plastic.com began not long after the tech-centric NASDAQ peaked in March of 2000 and began its first gradual and then precipitous decline. By November of that year, just as Plastic.com was recruiting its partners and sourcing content, most Internet stocks had dropped 75% or more. The epic failures of sites like Pets.com and theGlobe.com signaled to investors that the jig was up. The bubble had burst.

By the time of the site’s launch, in January of 2001, very few dot-com companies were left. Plastic.com found themselves unable to sell even a single ad, let alone recruit additional investment to keep it afloat. They could draw people to the site, but the eyeballs had no value. They couldn’t pay their writers or their staff. They even had to turn to readers for money, soliciting donations in the space that was supposed to be reserved for advertising. But it wasn’t enough.

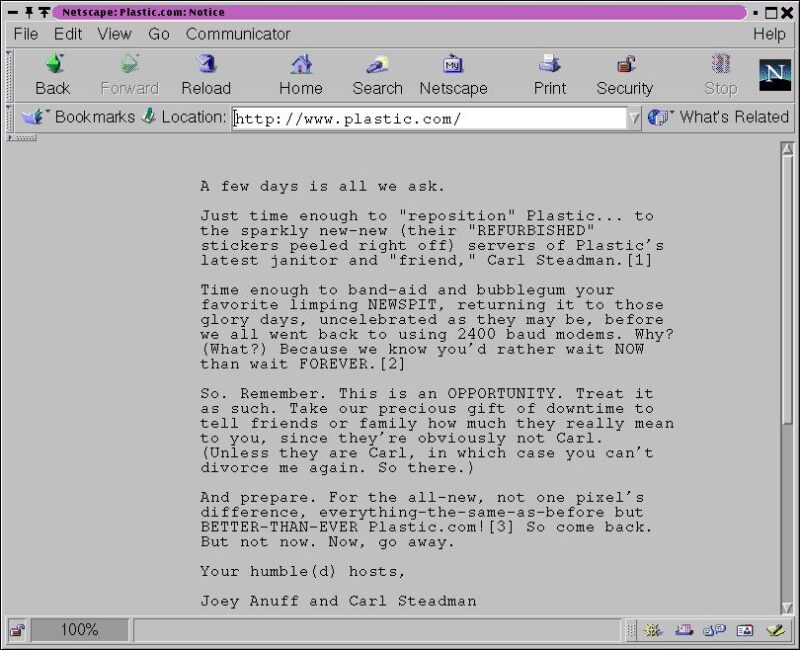

Before it’s first anniversary, Plastic.com was already in the process of being sold. After being passed on by major outlets, the site found an unlikely buyer. Carl Steadman had originally created Suck with Anuff in the basement of Hotwired. He also served as its first editor before he left for personal reasons, ceding control to Anuff and a growing staff. As Plastic.com tethered on the edge, Steadman came out of hiding to offer a deal.

To hear Anuff tell it, the original plan was for he and Steadman to run it together. That’s not how it ended up. In November of 2001, Steadman became the sole proprietor of Plastic.com. He had bought the site for just $30,000. The site meant to surprass Slashdot gone in under a year for peanuts.

Steadman retooled the site, made it smaller and more user-driven, with less reliance on outside users and editorial contributions. It ran for just over a decade before Steadman was finally forced to close it down. But it never quite reached its potential.

Slashdot, meanwhile, is still around (though none of its creators remain at the site). The Slashdot effect is not.