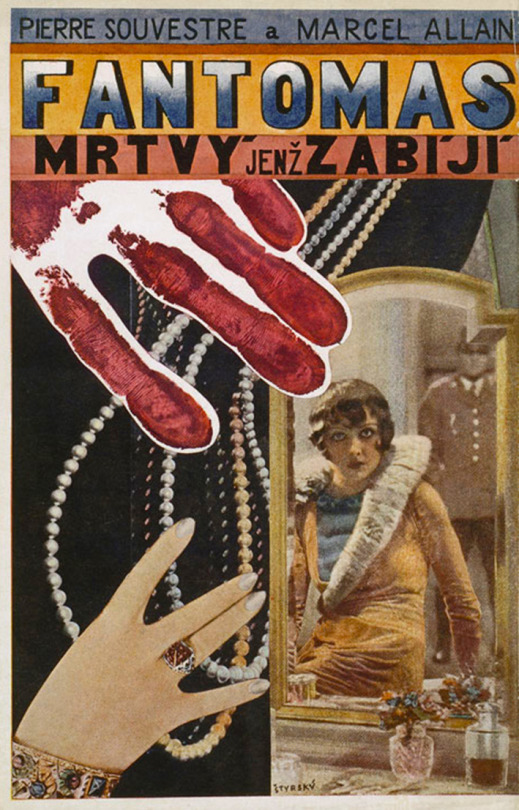

Fantômas

by Jindřich Štyrský

(Cover by Jindřich Štyrský)

In one of his surrealist texts, Robert Desnos recalls when the first Fantômas books began to appear in Paris, remembering their alluring titles and spellbinding, color covers: “A new volume came out each month … Le Mort qui Tue … Le Pendu de Londres … La Fille de Fantômas … we eagerly awaited more …”

It is no accident that Fantômas returns in the memories of one of the leading young French poets. Fantômas passed through an entire era of French poetry, and for a time was the literary sensation in France. He passed through the work of Apollinaire, Max Jacob, Philippe Soupault, Jean Cocteau, P.M. Orlan, Paul Dermée, and André Breton; Francis Poulenc began to compose the music to a libretto freely adapted from Fantômas, just like André Favory based the blood-soaked work of his early period on ideas inspired by his reading of Fantômas. In France, where opposites and extremes rub shoulders without destroying one another, where in the realm of poetry tradition lives side by side with Dada, where there are no phony biases, the best poets were able to love the fantastic stories of the “legendary outlaw Fantômas whose name filled the whole world with dread,” while feeling no shame that these editions of “pulp fiction” occupied a place on their shelves next to the immortal Proust and Balzac.

How this multivolume series got its start is the stuff of legend. Those in the know say – not in the academic tomes of literary history of course – that several different authors participated in writing the Fantômas series, among whom were included Apollinaire, Max Jacob, André Salmon, and Pierre Reverdy. Others claim that Fantômas was created by an unknown, washed-up journalist who consulted firsthand with criminals and hookers of the Parisian demimonde. The most likely version is the one supported by the Paris publisher Arthème Fayard, who claims that Fantômas was the brainchild of Pierre Souvestre and Marcel Allain (whose existence is shrouded in mystery), with the former disappearing about ten years ago somewhere in South America and the latter falling in the Great War. – The Fantômas books contain such a concentration of horror, blood, corpses along with so much poetry, moonlit nights, garden parties, the sea, and maidenly charm, that it is hard to imagine it was written by a mediocre writer/storyteller. The fact that the Fantômas tales are often based on contemporary and historical crimes, sensational trials, and official and classified police records clearly suggests that it was written by someone with inside information. Some of the volumes are analogous to actual great crimes, such as: the Gerard case of 1911; the infamous “corpse in the suitcase” of 1889 (Lille); the crime on rue Montaigne (the Pranzini Affair); “the severed hand” found at Aix-les-Baines in 1903; or the so-called “broken dagger affair” (Meynier and Madeleine Delvigne) from 1909, which had its finale one fine morning on Place de la Roquette.* The real and tragic sources of these fantastic stories and mysteries shimmer on the pages of Fantômas, their horror and novelty bringing to mind the magnified details of insignificant things, the sight of which leaves us quaking in terror.

Only after the success of Fantômas – a success of the literary and the universal – after the popularity it enjoyed in France, several other French authors – Leblanc, Marcel Nadaud, André Fage, Maurice Pelletiere, et al. – began to adopt this form and mode to write crime stories. The English and the Americans also adopted the template of this new type of novel – Sapper, Martyn, and Packard (see The Grey Seal) – but they have produced only a pedestrian form of detective fiction.

* Prisons were located on both sides of rue de la Roquette and the site witnessed myriad executions.

• An outtake from Dreamverse by Jindřich Štyrský (Twisted Spoon Press, 2018). It was originally published in Czech in Odeon, literární kurýr, no. 8, May 1930, and is translated here by Jed Slast. All rights reserved.