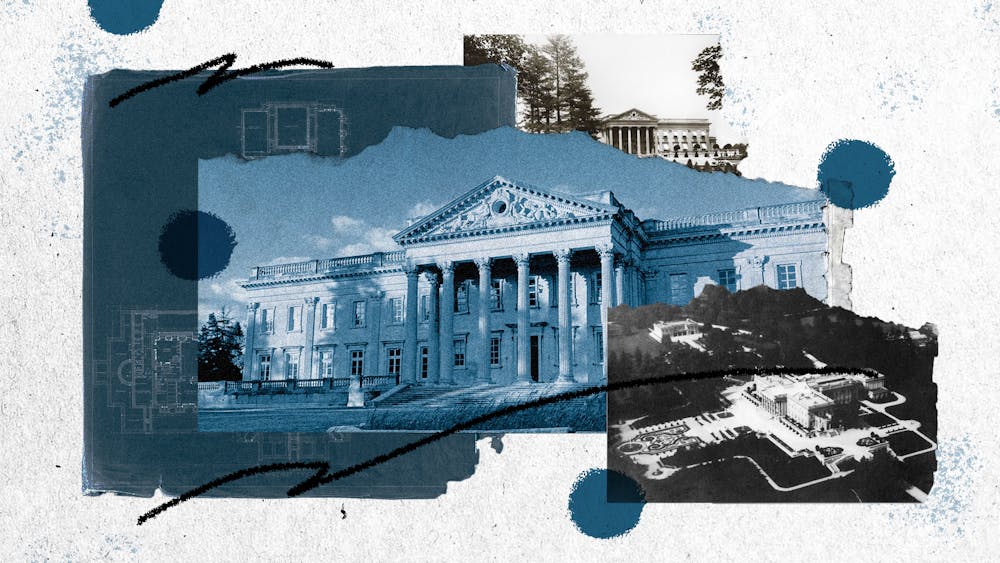

Adorned with collections of renowned works by artists like Rembrandt, Raphael, Velasquez, Titian, Bellini, Donatello, Monet, and Van Dyck, this architectural wonder once sheathed some of the most revered artistry from across the globe. Engulfed by 33 acres worth of decadent French gardens composed of grandiose marble fountainheads, the Corinthian columns chiseled from marble welcoming incoming company bear a striking resemblance to the Greek marvels resting atop the Acropolis. But, this is not the Louvre. This is not Versailles. This is not the Temple of Athena. This is Lynnewood Hall.

The original construction of Lynnewood Hall, just outside of Philadelphia in the heart of Cheltenham Township, was finalized in December of 1899 and celebrated with the arrangement of its resplendent opening gala. The original owner of Lynnewood Hall, Peter A.B. Widener made his fortune as an industrialist. Fascinated by the existing architectural wonders of architect Horace Trumbaer, Widener called upon Trumbaer’s dexterity to design Lynnewood. Over the course of a few years, Widener and his son, Joseph, developed one of the most renowned art collections across the entire country, and arguably the world, housed in none other than Lynnewood Hall.

Edward Thome, the Executive Director of the Lynnewood Hall Preservation Foundation, recounts that the Widener family truly was integral to the Philadelphia community. Widener founded the Philadelphia Traction Company (PTC), which is now part of the Southeastern Pennsylvania Transportation Authority (SEPTA), our well-known and frequently utilized transportation system. The Wideners also had major connections between hugely influential contemporary companies including Standard Oil, Standard Steel, and the RMS Titanic. Thome notes that in addition to their economic contributions, “they were very generous with their art," publicly offering its viewing to visitors throughout the summer months, before eventually donating it in its entirety to the National Gallery of Art in 1939, where it can be seen for free to this day.

“It was one of the single most significant cultural gifts from any one family to the American people in U.S. history,” says Thome.

However, after Joseph Widener, the sole heir of the property, passed away in 1943, the house and its remaining contents were put up for auction in 1944. The property faced a period of severe neglect and harsh deterioration. Lynnewood Hall sat dormant for roughly eight years. But now, after a subsequent sequence of ownerships, a roof leak in the Van Dyke gallery, and its eventual acquisition on behalf of the Lynnewood Hall Preservation Foundation in June of 2023, restoration plans have begun.

The property will undergo a phased restoration, which will take place over 25 years. Aside from the extensive abandonment and water damage, the mansion remains structurally intact. The Foundation plans to incrementally relinquish more and more of the property to the public eye until it can eventually embody a cultural center and art museum.

Beyond allowing the physical property to flourish, Angie Van Scyoc, Chief Operating Officer for Lynnewood Hall Preservation Foundation, says that they “want to utilize the process of preservation and restoration to implement educational programming," allowing individuals interested in property restoration to gain exposure to the intricate and refined skill set needed to make projects like Lynnewood Hall succeed. Their ultimate goal is to curate a “cultural hub and educational incubator for the community,” says Thome. The historical relevance of the property will hopefully encourage both Philly natives and interested visitors to absorb Lynnewood Hall’s fascinating narrative.

In fact, one of the central components contributing to the project’s success is the Philadelphia community. There exists a strong interest in revitalizing a significant constituent of Philly’s artistic culture. Alongside revitalizing what has been a sacred quarter for a vast collection of historical works, the Preservation Foundation aims to engage the community and increase public involvement with a critical piece of our city’s past. Van Scyoc says that to them, it is vital that people resonate with the idea of being able to “keep their sense of place and be proud of their heritage.”

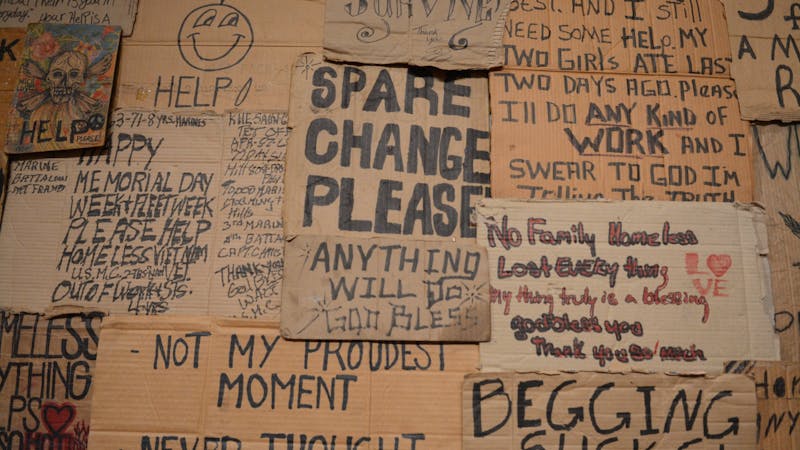

At the core of reviving the property and promoting its art is the shared human experience. “Due to a lot of the tragedy and loss that befell the family over the years, we really do believe that the art was a therapy for them,” says Thome. The Wideners experienced innumerable misfortunes, and turned to art as a unifier. The Preservation Foundation hopes that regardless of background, this shared experience of loss, grief, and optimism will facilitate a connection between the art and the viewer.

The art also remains the inspiration for the specific engineering decisions made during the house’s original construction, as well as its renovation. “It’s not just a beautiful piece of classical architecture, but it has so much craftsmanship. There’s artisanry within just how each room was crafted.”

Referred to as “The Last of the American Versailles," its striking resemblance to such remarkable works of architecture makes Lynnewood Hall a Philadelphia marvel. “The house was built for family and art, but one of the most profound aspects of the art that still remains even though most of it is at the National Gallery is the house itself. The most public form of art is architecture,” says Van Scyoc.

This magnificence, as well as the Preservation Foundation’s emphasis on community engagement and educational impact, differentiates Lynnewood Hall and truly makes it an undertaking worthy of our attention.