Story highlights

A woman's risk of developing type 2 diabetes increases with years of shift work

Almost one-fifth of the workforce is on some kind of rotating night shift

Circadian rhythms play a critical role in maintaining healthy blood-sugar metabolism

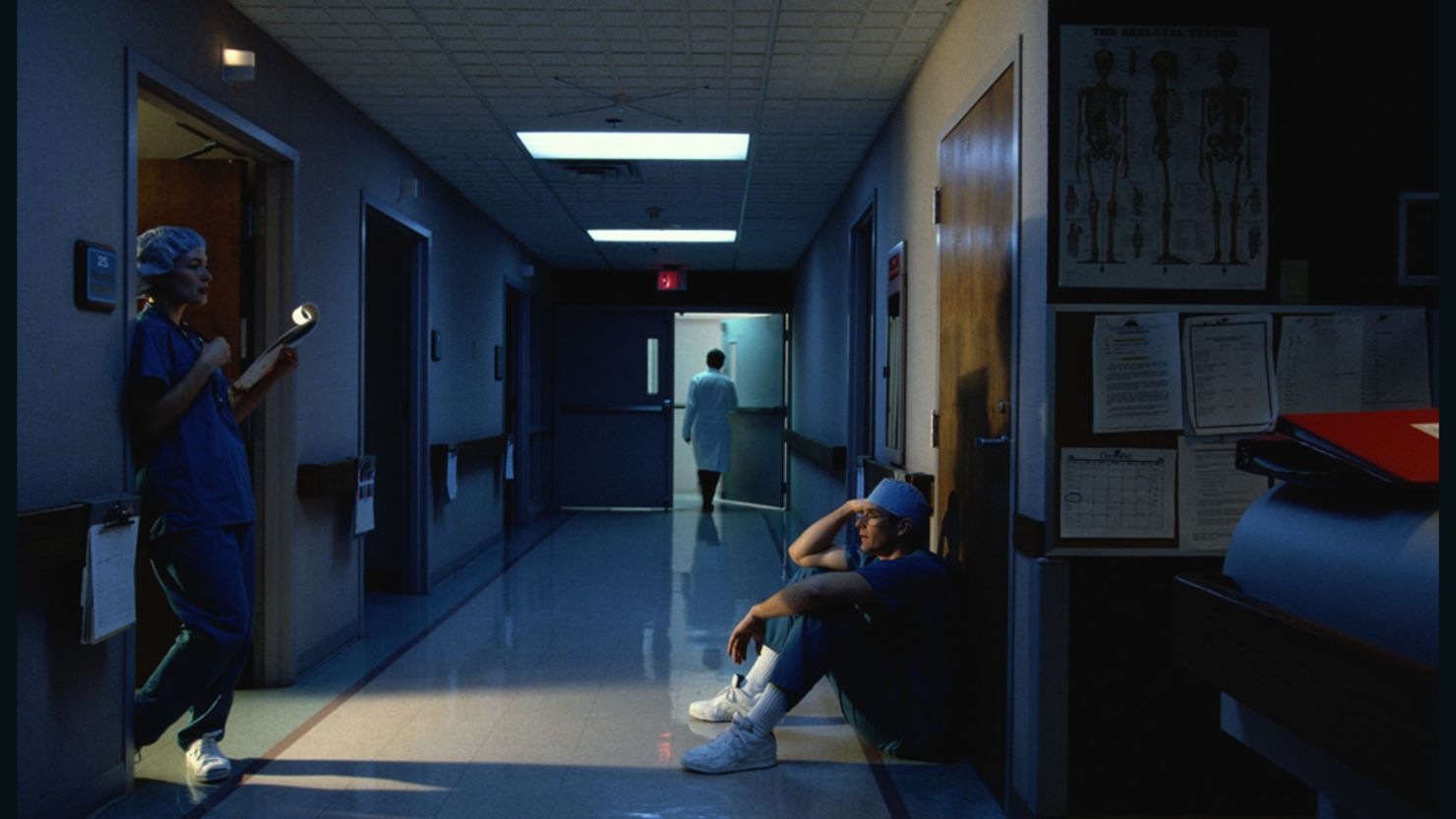

Women whose jobs require them to rotate through day and night shifts may be increasing their diabetes risk, especially if they maintain that schedule over a long period of time, a new study of nurses suggests.

A woman’s risk of developing type 2 diabetes increases steadily with the years of shift work she puts in, the study found. Compared to nurses who worked days only, those who worked periodic night shifts for as little as three years were 20% more likely to develop type 2 diabetes, while those who clocked at least 20 years of shift work were nearly 60% more likely to develop the disease.

“The increased risk is not huge, but it’s substantial and can have important public health implications given that almost one-fifth of the workforce is on some kind of rotating night shift,” says senior author Frank Hu, M.D., a professor of nutrition and epidemiology at the Harvard School of Public Health, in Boston.

Health.com: Could you have type 2 diabetes? Know the signs

Much of the increase in diabetes risk can be explained by weight gain – a common and well-known side effect of shift work, which disrupts eating and sleeping schedules in ways that can make following a healthy lifestyle a challenge. But other, more subtle disturbances may also play a role.

Irregular work hours tend to disrupt the body’s circadian rhythms (also known as the “body clock”), which play a critical role in maintaining healthy blood-sugar metabolism and energy balance, Hu says. Previous studies in both humans and animals have shown that sleep deprivation and irregular sleep-wake cycles can lead to insulin resistance and rising blood-sugar levels – both hallmarks of diabetes.

Our internal clock may influence our ability to metabolize certain foods at certain times, says David J. Earnest, Ph.D., a professor of neuroscience and experimental therapeutics at the Texas A&M Health Science Center College of Medicine, in College Station.

Health.com: 25 ways to cut 500 calories a day

If you raid the refrigerator for a late-night snack of ice cream, the enzymes and systems needed to turn high-fat foods into energy may not be alert enough to handle the barrage, and as a result those calories may end up as fat rather than fuel, Earnest says. Similarly, he adds, a meal of bacon and eggs may be less healthy if eaten after sundown than after sunrise.

“In the past 25 years, we’ve focused a lot on lifestyle issues such as maintaining a healthy diet and avoiding a sedentary lifestyle,” Earnest says. “But regardless of whether you’re a shift worker or not, that may not be enough to avoid these health issues.”

In fact, Earnest says, the new findings may have implications not only for shift workers, but also for anyone who works crazy hours.

“Most professionals work really irregular schedules,” he says. “This could be an important factor in… the increased incidence of type 2 diabetes in Western societies.”

Health.com: Job killing you? 8 types of work-related stress

In the study, which appears in the journal PLoS Medicine, Hu and his colleagues analyzed data on 177,184 women between the ages of 42 and 67 who were followed for about two decades as part of the long-running Nurse’s Health Study. The women were considered rotating night-shift workers if they worked at least three nights per month, in addition to day and evening hours.

The increase in type 2 diabetes risk associated with night shift work ranged from 5% in nurses who’d worked that schedule for one or two years to 58% in those who’d done so for at least 20 years. When the researchers factored body mass index into the equation, the increased risk in the same groups dropped to 3% and 24%, respectively.

It’s not clear how much of that remaining risk might be attributed to body-clock disruptions. Hu and his colleagues attempted to rule out alternative explanations by controlling for a wide range of factors, such as a family history of diabetes, diet, smoking, and sleep deprivation.

Health.com: Exercise tips for people with type 2 diabetes

Shift workers tend to sleep less, smoke more, and eat less healthy diets than other people, Hu says.

“The overall risk associated with rotating shift work is probably due to the combination of biological factors resulting from disruption of circadian rhythms and… behavioral risk factors,” he says.

The study was the largest to date to explore the link between shift work and diabetes, but the authors stress that more research will be needed to confirm the results, especially in other populations. The study included only female nurses and the vast majority were white, so the findings don’t necessarily apply to men or other ethnic groups, they say.

Copyright Health Magazine 2015