Not a great deal is written or even known today about the connection between Jews and Native American Indians. It is, however, a fascinating subject.

There is much sentiment behind the affinity of Jews and Jewish history with that of American Indian tribes. The atrocities inflicted upon their people were a key factor that resulted in diminishing their population by 90% – from a high of about 10 million in 1492 to a low of 250,000 at the beginning of the 20th century. Their numbers are slowly recovering.

Common roots

According to a Ynet report, a population of Native American Indians from the US state of Colorado has been found to have a genetic mutation typical of Ashkenazi Jews. The finding suggests the presence of common roots that date back to the days of Christopher Columbus.

Several stories circulate on this subject.

In 1650, Rabbi Menashe Ben Israel, Chief Rabbi of Amsterdam, recorded in his book Mikveh Yisrael a conversation that he had with a Jewish Dutch explorer of the Americas. The explorer related how he made contact with the Native Americans but after trying to communicate with them in every possible European language, he had no success. Both he and his first mate, being Jews, they began to talk among themselves in Hebrew. To his utter amazement, upon hearing them speak Hebrew, the Native American chief responded by saying “Shema Yisrael.”

In 1775, Englishman James Adair, after living with Native Americans for 40 years, recorded his experiences and published a book about them in London titled The History of the American Indians. Almost his entire work is dedicated to documenting and proving that the Native American tribes of the central and southern territories were definitively of Jewish origins and to his day maintained a sizable amount of their ancient Israelite heritage. Among the points of similarity between the Jews and Indians, Adair emphasized the division into tribes, notions of a theocracy, of ablutions and uncleanness, cities of refuge and similarities in life cycle practices such as divorce. He goes so far as to say that the tribes he knew worshiped a single God whom they called in their language Ye’ho’wah.

Even President Thomas Jefferson in 1803 was aware of Adair’s book and made mention of it in one of his letters to John Adams. Jefferson quotes Adair’s belief that “all the Indians of American [are] descended from the Jews: the same laws, usages; rites and ceremonies, the same sacrifices, priests, prophets, fasts and festivals, almost the same religion, and that they all spoke [some] Hebrew.”

Common history

In the early 1870s, US president Ulysses S. Grant appointed Dr. Herman Bendell, a Jewish doctor from New York, as Superintendent of Indian Affairs.

Because he was a Jew, the newspaper The Boston Pilot feared that Bendell would undo the good work of Christian missionaries and start spreading Judaism among Arizona’s native Americans. In fact, Bendell’s Judaism was one of the reasons that Grant appointed him, because he wanted someone who would not prioritize missionary work.

Bendell quickly emerged as a champion of Native rights within the government. He wrote, “I feel it is a duty I owe to the people of the country and the Indians under my charge to do something to relieve the pressures that surround them.”

The continuous intense opposition to Bendell’s Jewish faith made his job impossible, so after two years he resigned, returned to Albany, married his childhood sweetheart Wilhelmine Lewi, and practiced medicine. In a Walter’s World program some time ago Wiesenthal Center dean Rabbi Abraham Cooper said that antisemitism in America was nothing new. Well, here we have proof from the 19th century.

When Bendell died in 1932, few people realized that this long-time New York state ophthalmologist, had once worked to secure Indian rights in pre-state Arizona.

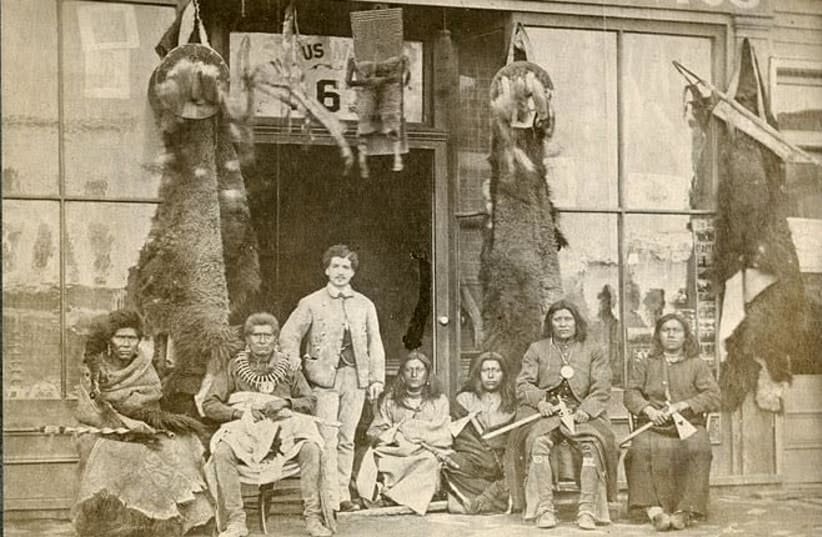

THEN THERE was the story of Julius Meyer, who as a teenager in 1866 moved from his birthplace in Prussia to Omaha sometime before Omaha was incorporated as a city and Nebraska was admitted to the Union as a state. He joined his older brothers Max, Moritz and Adolph, who had founded a cigar store and a jewelery and music store.

Young Julius found his own niche and traded the cigars and jewelery from their stores with Native American tribes. He would travel on horseback deep into Indian-controlled territory, living for weeks with Native American tribes and traders. He spoke several Native American tongues, which set him apart from many European traders, and served as an interpreter for Gen. George Crook. He also treated Native Americans fairly, earning him the sobriquet Box-Ka-Re-Sha-Hash-Ta-Ka (Curly-Haired White Chief Who Speaks with One Tongue), a reference to his wavy locks and also his straight, honest way of doing business.

Despite living with Native Americans for weeks at a time, Julius was known to be keeping Jewish dietary laws, so that when he was invited to feasts with tribesmen, his hosts knew to serve him hard-boiled eggs instead of the non-kosher meat that everyone else enjoyed.

Back in Omaha, Julius set up a popular “Indian Wigwam” store, selling Indian-made items. In 1909 at the age of 60 he died in mysterious circumstances. It was reported as a suicide, that he shot himself first in the temple, then in the chest, with his left hand. But he was right-handed. No alternate theory was ever put forward, and he was mourned throughout the American West as a tragic case of suicide.

AROUND THE same time, in 1869, Solomon Bibo, another teenager from Prussia arrived in America and settled in the New Mexican town Ceboletta to join two of his older brothers who had come to the United States some years before. Like most Jews in the American West, the Bibo brothers worked as traders, but they were far from ordinary. Unlike many Europeans at the time, they quickly garnered a reputation for fairness and honesty when dealing with Native Americans.

Solomon Bibo quickly learned Queresan, the language of the local Acoma tribe and immersed himself in their concerns, championing Acoma rights against Mexican and American ranchers, and against the US government, which he accused of trying to cheat the Acoma out of their rightfully owned lands. As a result, in 1877 the US government offered the Acoma a treaty guaranteeing the tribe 94,000 acres of land, far less they felt they deserved. In order to protect their remaining lands, the Acoma leased their land to Bibo for 30 years in exchange for an annual payment of $12,000 and assurances that Bibo would protect the land from squatters, ensure that coal on the tribe’s land was mined and that the tribe would receive the proceeds.

Learning of the agreement, Pedro Sanchez an Indian agent from Santa Fe, wrote to the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, complaining about Bibo, “the rich Jew,” and tried to get the lease invalidated on the grounds that the tribe as a whole had not agreed to the arrangement. Bibo found himself facing not only the loss of the Acoma lease, but the loss of his trader’s license as well. The Acoma nation quickly mobilized itself, providing a petition with a hundred signatures to the Bureau of Indian Affairs assuring they had confidence in Bibo.

Eventually, Solomon Bibo married Juana Valle, the granddaughter of the Acoma chief, and he later became Chief of the nation himself, pushing for educational and infrastructure reforms. Juana began to adopt a Jewish lifestyle. But two years before the turn of the century, Solomon and Juana moved to San Francisco in order to provide their six children with a Jewish education. Solomon died in 1934 and Juana in 1941. Their children said kaddish for them.

Wolf Kalisher in 1826 moved from Poland to Los Angeles, and 29 years later became a United States citizen. After the Civil War, He and Henry Wartenberg started a tannery, one of that city’s first factories. Kalisher went out of his way to hire Native American workers and championed Native American rights. At the same time he became a pillar of the developing Los Angeles Jewish community and with his wife Louise raised their four children and helped establish one of the city’s first synagogues.

He became particularly close with Manuel Olegario, a leader of the local Temecula tribe, advising and assisting the chief as he campaigned to protect his tribe’s land in San Diego County. Kalisher Street in Los Angeles memorializes Wolf Kalisher and his efforts on behalf of Native Americans to this day.

Not all Jewish businessmen used their connection with American native Indians to further the interests of the tribes or even to mutual advantage.

Otto Mears was born in Kurland, Russia, on May 3, 1840, to an English father and a Russian mother. His parents were both Jewish, but otherwise little is known about them. After a troubled childhood and in his early teens, he arrived in San Francisco to join an uncle who lived there. It was the height of the Gold Rush and young Otto soon found himself practicing successful financial speculation.

At the outbreak of the Civil War in 1861 he joined the California Volunteers and took part in several actions including the army’s campaign against the Navajo, which was led by Kit Carson in 1863–64.

Following that episode, he moved north to become a merchant which brought him into contact with the Ute Indians. He learned their language and, so it is reported, spoke it with a Yiddish accent. Mears saw an opportunity to exploit that relationship and managed to obtain US government contracts.

Through his government connections he became involved in the infamous Brunot agreement between the US government and the Ute to cede some of their land. Mears acted as advisor to Chief Qurey, the unofficial Ute negotiator.

Mears’ interest, however, was to take over the vast area and he played a key role in the removal of the Ute tribe of Colorado from their land in which they lived for more than 400 years, according to the Colorado Encyclopedia.

He used the land to build miles of railroad and more than 450 miles of toll roads across Ute owned land to facilitate his many business interests including the Mears Transportation Company. His transportation empire transformed Southern Colorado.

Today, about half of the 4,000 members of the Ute tribe live on the reservation in North Eastern Utah, the second largest in the United States, covering about 4.5 million acres according to one report, but 1.2 million, according to other documents. A stained-glass window situated directly above the entrance to the Colorado State Senate Chamber is Colorado’s Monument to Otto Mears

Common vision and goals

In New Jersey, Santos Hawk’s Blood Suarez is an Apache activist who brings fellow Native Americans to pro-Israel events. He insists that there are strong parallels between Native Americans and Jews. Both groups have lived in exile; Jews show that it is possible for a native people to return to their native land and revive their ancestral language, even after thousands of years.

“I admire the people who take a stand. That’s why I admire the people of Israel: They’re people who stand up to defend their homeland,” said Suarez.

The first female head of the Rappahannock Tribe in Virginia is Chief Anne Richardson. She’s also a strong supporter of the Jewish state. In 2013, she and another female chief, Kathy Cummings-Dickinson of the Lumbee Tribes in North Carolina, visited Israel. Wearing their ceremonial robes, the chiefs brought a poignant message to the Israeli government.

“We are here to deliver a message to the residents of Israel: Stand firm and united against the threats and pressure… We want to encourage Israel not to give in to those who try to pressure them to give up parts of the homeland. Surrender to this pressure is not a recipe for peace, but rather war. We stand beside you.”

Watching coverage of Israel’s 60th Independence Day festivities in May 2008 was a revelation for David Sickey, the vice-chairman of the Governing Council of the Sovereign Nation of the Coushatta Tribe of Louisiana. After learning more about the Jewish State, he realized there were some incredible parallels between Israel and his own nation.

When Sickey presented his idea of fostering relations between the Coushatta nation and Israel, his tribal chiefs were enthusiastic, as the Coushatta value sovereignty and nationhood much like the Jewish people, and autonomy is something to be embraced.” Asher Yarden, then Israel’s consul, visited the tribe for an official ceremony to establish formal ties.

“It was a highlight, if not the highlight, of my 25-year career with the Ministry of Foreign Affairs,” he recalls.

The Coushatta adopted May 14, Israeli Independence Day, as a holiday called Stakayoop Yanihta Yisrael (The Day to Honor Israel). A Coushatta delegation visited Israel in 2009 to foster economic ties. The tribe is currently the American distributor of Aya Natural, an Israeli Druze-owned company that produces olive oil-based cosmetics in Israel’s North. Israeli engineers are also aiding Coushatta fish farmers in importing hi-tech Israeli fish-farming technology. Sickey said, “Israel is a very dynamic nation, and it makes sense for the tribe to partner with a very robust nation and the only democracy in the region.”

RYAN BELLEROSE is a native North American from northern Alberta, Canada and member of the Metis nation who so identifies with Israel as the indigenous people of our region that he launched, together with a Jewish girl, a successful pro-Israel organization called “Calgary United with Israel” and was hired by a Canadian Jewish organization as an advocacy coordinator.

He grew up living rough on a reservation speaking Cree until he was five years old. As he grew up, he came to believe that Israelis and the Métis shared historical attributes.

This is what he told me: “Because Jews and Indians are both ethno-religious tribal indigenous peoples, we have a high level of sympatico that may seem odd to outsiders, but is based on the fact that we both deal with issues of language loss, culture loss and assimilation. We seem to understand each other and our communities’ concerns easily. During my travels, I have come to understand that this is not a one-off occurrence; in fact Jews and my people tend to see the world through a very similar lens, so we easily find common ground. We are both survivors of multiple attempted genocides and takeover of our indigenous homeland by outsiders and we see ourselves as survivors, not victims.”

NOW HERE is an interesting fact showing a different Jewish connection to American Indians. Researchers at Israel’s Sheba medical center near Tel Aviv have found an unexpected link in a group of Native Americans living in Colorado – to Jews. It is a genetic mutation that predisposes carriers to breast and ovarian cancer and is found disproportionately in Jews of Ashkenazi origin.

Researchers conducted additional genetic testing and identified a common ancestor: a Jew who came to South America from Europe some 600 years ago, about the time that Jews were forced out of Spain and Christopher Columbus discovered the New World. The mutation among the Native American population is identical to that found among Ashkenazi Jews, offering solid proof of long-ago Jewish intermarriage with Native American tribes.

After that, it is perhaps not surprising that American Indian Tribes support the State of Israel, and I salute the American Indians.

Walter Bingham at 97 holds the Guinness World Record as the world’s oldest active journalist and radio host. He presents ‘Walter’s World’ on Israel National Radio (Arutz 7) and ‘The Walter Bingham File’ on Israel Newstalk Radio. Both are in English