Where the Vast Sky Meets the Flat Earth: Framing Plains Indians

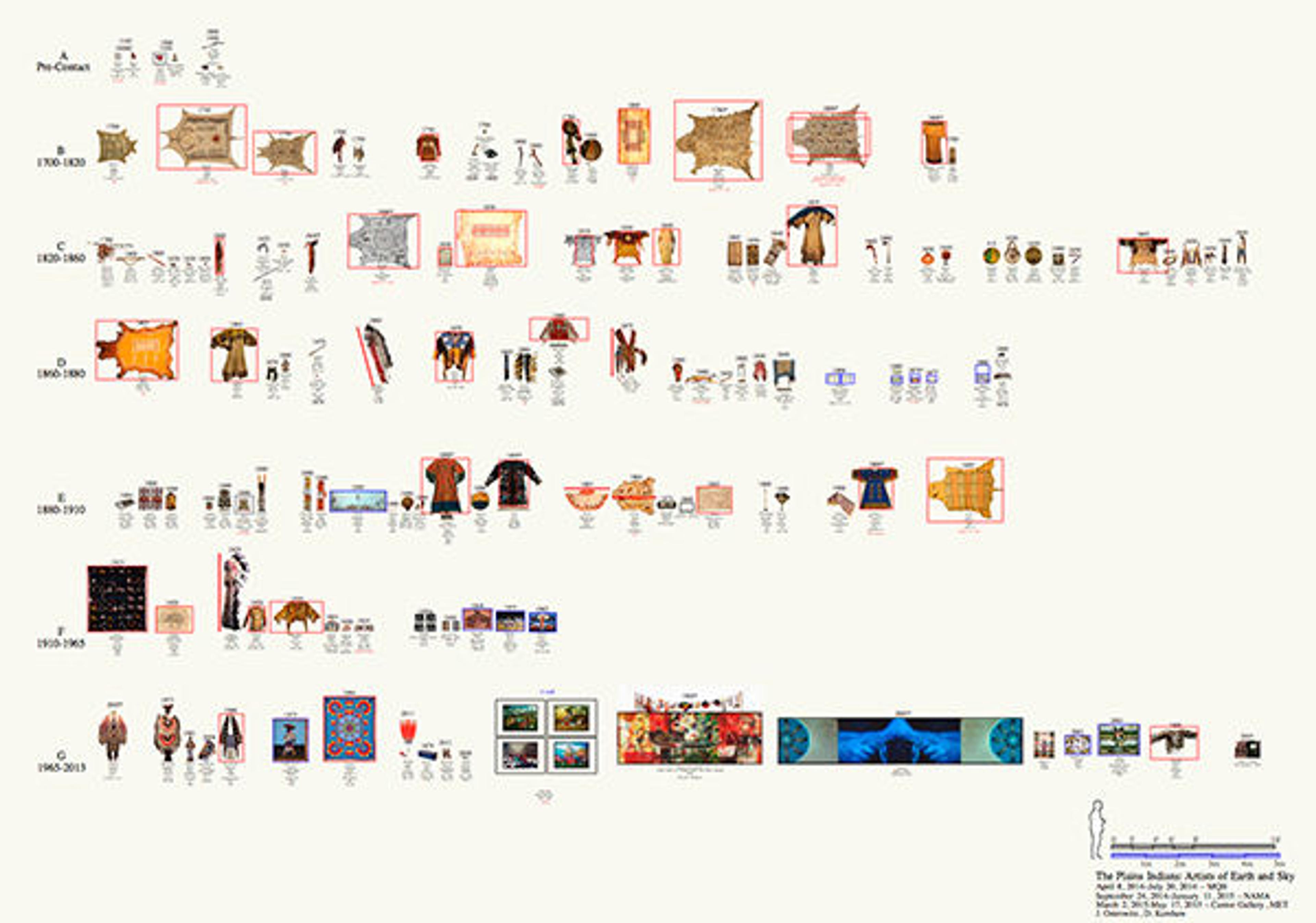

Artworks on display in Plains Indians: Artists of Earth and Sky, arranged chronologically. Image courtesy of the author

«When I began thinking about the installation plan for the exhibition Plains Indians: Artists of Earth and Sky almost two years ago, I started organizing the artworks and contemplating the layout of the scheduled gallery. The Iris and B. Gerald Cantor Exhibition Hall (gallery 999) is usually divided into rooms, or a sequence of manageable spaces, but somehow this seemed inappropriate for an exhibition focused on art devoted to, and deeply reflective of, its overwhelming natural environment. Almost none of the objects, with the exception of modern and contemporary works, needed to be mounted to a wall, so that left most of the walls of the Met's second-largest special exhibition gallery available.»

Gallery view of Assyria to Iberia at the Dawn of the Classical Age (September 22, 2014–January 4, 2015), as installed in the Iris and B. Gerald Cantor Exhibition Hall. Photo by Anna-Marie Kellen

The last thing I wanted to do was to put these masterpieces of Native American art in small spaces or areas with bare walls. Working with Research Associate Judith Ostrowitz from a checklist with detailed dimensions for each object, we first organized all the materials chronologically, and then started to group the artworks thematically. On my floor plan, I started removing existing nonstructural walls until only those required for specific works remained. An enormous space, punctuated by two rows of columns, remained.

To frame these works in an appropriate setting, I started hunting for dramatic, yet not overwhelming, photographs of the vastness of the sky over the flatness of the plains. Most of the finest images were by non-Native American professionals, however, and I really wanted a young, talented Plains Indian photographer to be represented—one who wouldn't mind my cropping or adjusting their image to suit the space and the artworks. Judith and I searched for a suitably inspired student at tribal high schools and eventually found three potential candidates. One in particular, Shania Hall, a member of the Blackfeet Nation reservation, eagerly jumped into the challenge, even snowshoeing with her teacher to explore potential sites.

Shania Hall at work near Heart Butte, Montana. Photos by Scott Mathews

The gallery's largest exposed wall would be 20 feet high and 117 feet wide, so I knew I needed an extremely high-resolution image in order to keep it from falling apart into individual pixels. Our wizards in digital imaging proposed using an extraordinary (but quite complex and expensive) high-resolution panoramic camera, which would require having a professional assist with the photography. I turned to my colleague Mort Lebigre, graphic designer for the exhibition and master of inexpensive technology, to help explore our options. After a lot of research, he found a Fuji wide-format instant camera that completely avoided any potential pixelation concerns by making the image molecular in resolution.

Shania and her teacher Scott Mathews traveled extensively to find a perfect location for the photographs, ending up near Heart Butte, Montana, where the Rocky Mountains meet the Great Plains. In high enough winds to require securing the camera to the tripod with duct tape and firmly holding it down, Shania shot sequential panoramas under rapidly changing light and cloud conditions. She photographed the sky at a stormy dusk, and again at 5:00 a.m. the following day. A conscious decision was made to create a timeless view by avoiding the distraction of the agriculture found at the border between the Blackfeet Nation and surrounding nontribal ranches.

Shania's images were then ink-jet printed on a vast roll of theatrical sharkstooth scrim and suspended from the three longest gallery walls. Not only is the final display visually engaging, it also fulfills my desire to have visitors encounter the objects in an environment which gives both context and an American Indian voice to the exhibition. I can't wait to see Shania's face when she sees her own work displayed here at the Met.

Digital rendering of the Plains Indians installation, with Shania's photography displayed in the background. Image courtesy of the author

Digital rendering of the Plains Indians installation, with Shania's photography displayed in the background. Image courtesy of the author

Plains Indians gallery view. Photo by Eileen Travell

Plains Indians gallery view. Photo by Eileen Travell

Related Link

The Plains Indians: Artists of Earth and Sky, on view March 9–May 10, 2015

Daniel Kershaw

Daniel Kershaw is an exhibition design manager in the Design Department.