A previously unknown, bird-like dinosaur species that is thought to have lived around 70 million years ago has been discovered.

Researchers found the fossilized remains of the "bizarre" new species in an area known as the Nemegt locality, which lies in the Gobi Desert of southern Mongolia, according to a study published in the journal PLOS ONE. This locality is well-known among paleontologists for being rich in dinosaur fossils.

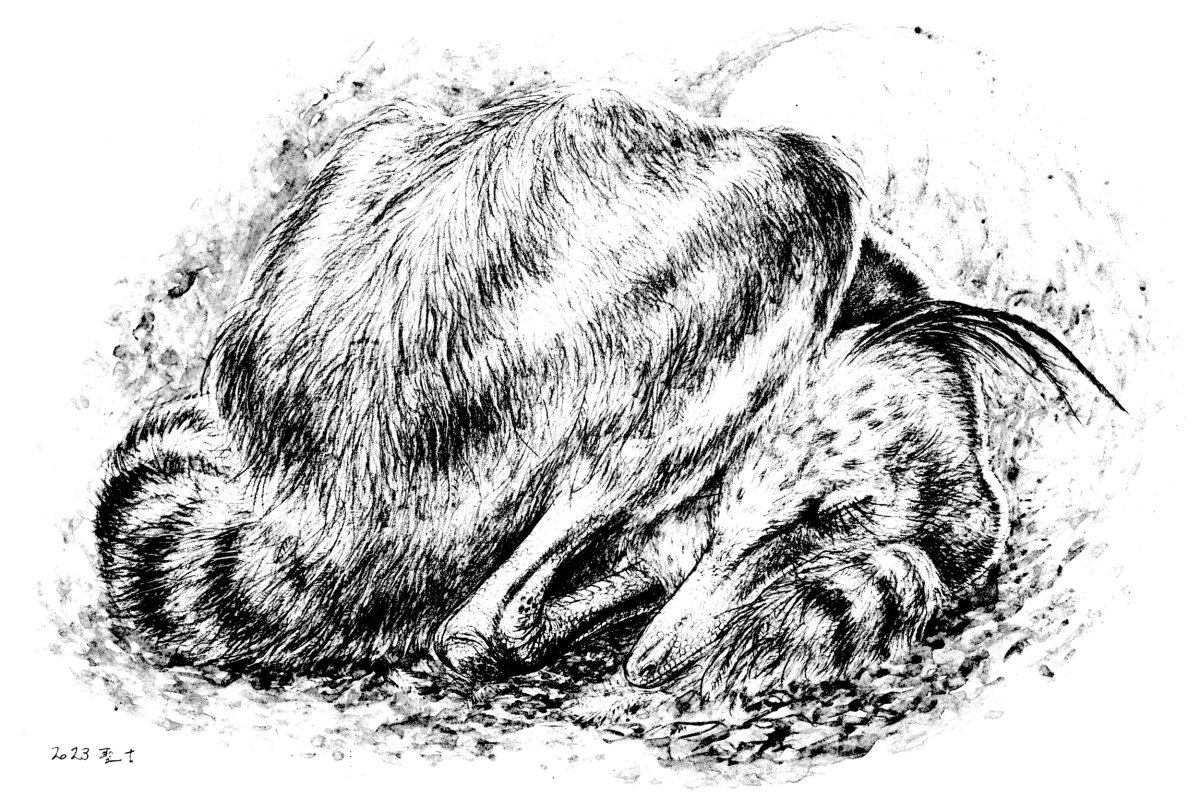

Intriguingly, the newly identified dinosaur, which has been named Jaculinykus yaruui, was found in a resting position that suggests it slept like modern birds—a rare discovery in paleontology.

Birds evolved from a group of primarily carnivorous and two-legged dinosaurs known as theropods. As such, they can be considered the only living dinosaurs. Theropods were a hugely diverse group that contained dinosaurs of various sizes, including giant predators like Tyrannosaurus rex—although birds are descended from the smaller members.

The latest findings shed new light on the evolution of avian behavior, according to the researchers.

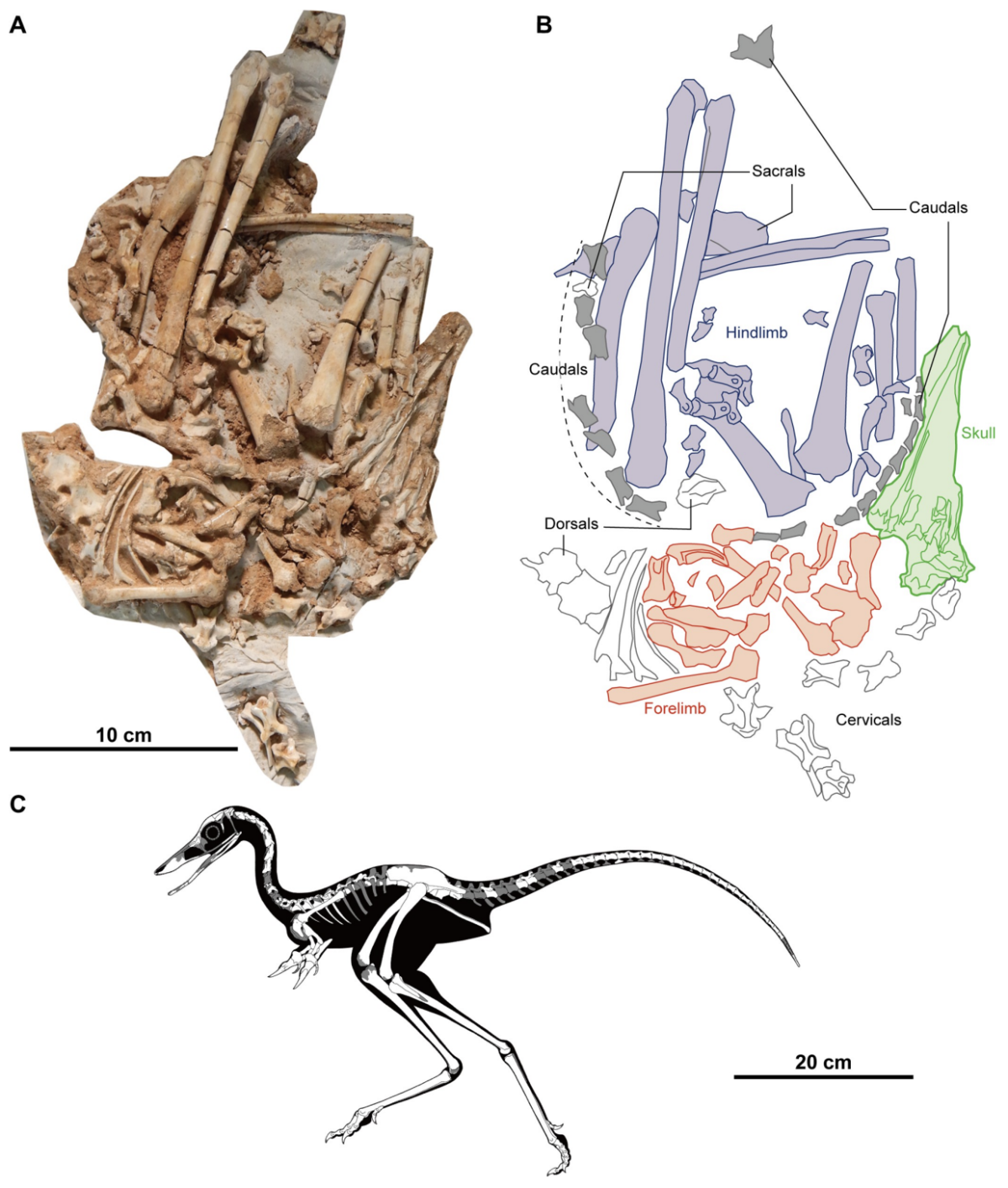

The J. yaruui specimen consists of a nearly complete and "exceptionally" well-preserved skeleton, which the authors of the PLOS ONE study found to represent a lineage of small theropod dinosaurs known as the alvarezsaurids.

These dinosaurs are known primarily from the Gobi Desert's Nemegt Basin—where J. yaruui was found—although they have been documented in several locations around the world, including the United States, Canada, Argentina, Uzbekistan, China and Mongolia.

These dinosaurs had many bird-like features and several "unique" characteristics, Kohta Kubo, an author of the study with the Paleobiology Research Group at Hokkaido University, Japan, told Newsweek. They are known from fossils dating to both the Late Jurassic period (around 163-145 million years ago) and the Cretaceous period (around 145-66 million years ago).

Jaculinykus yaruui was a small dinosaur that measured around 3 feet in length and likely weighed less than 65 pounds. It had a lightweight, bird-like skull with large eye sockets, extremely short forelimbs with two fingers and legs that were proportionally very long compared to the rest of the body, implying that it had advanced running abilities.

The first part of its scientific name, "Jaculinykus", consists of a reference to a small dragon or serpent from Greek mythology ("Jaculus") and the Latin word "onykus", which means claw. The second part of the name, "yaruui", is derived from the Mongolian word "yaruu" meaning speedy or hasty.

Perhaps the most fascinating aspect of the discovery is that the specimen was found in a position that suggests it was sleeping when it died.

"Most skeletal elements of the new alvarezsaurid specimen remain in their original position," Kubo said. "The skull is directed to its back and rides on its tail and hind limbs. Both hind limbs are folded under the pelvis. The neck and tail are curved."

According to Kubo, this position is clearly distinguished from the "death pose" of alvarezsaurid dinosaurs as well as being "identical" to rare specimens of closely related "troodontid" dinosaurs that have been found in what researchers believe are sleeping postures.

Modern birds sleep in a "tuck-in" posture when they sleep. In this position, the head is tucked onto the back, with the beak nuzzled into the feathers, while the legs are folded. This posture is thought to help with heat conservation. The new alvarezsaurid was found in a position that is very similar to this posture. Its long neck and tail are curled up with the head lying to one side of the torso, while the legs are folded under the pelvis.

Kubo said the particular J. yaruui individual documented in the study must have died in some kind of rapid burial event—its burrow may have collapsed, for example—in order to preserve the skeleton in this position.

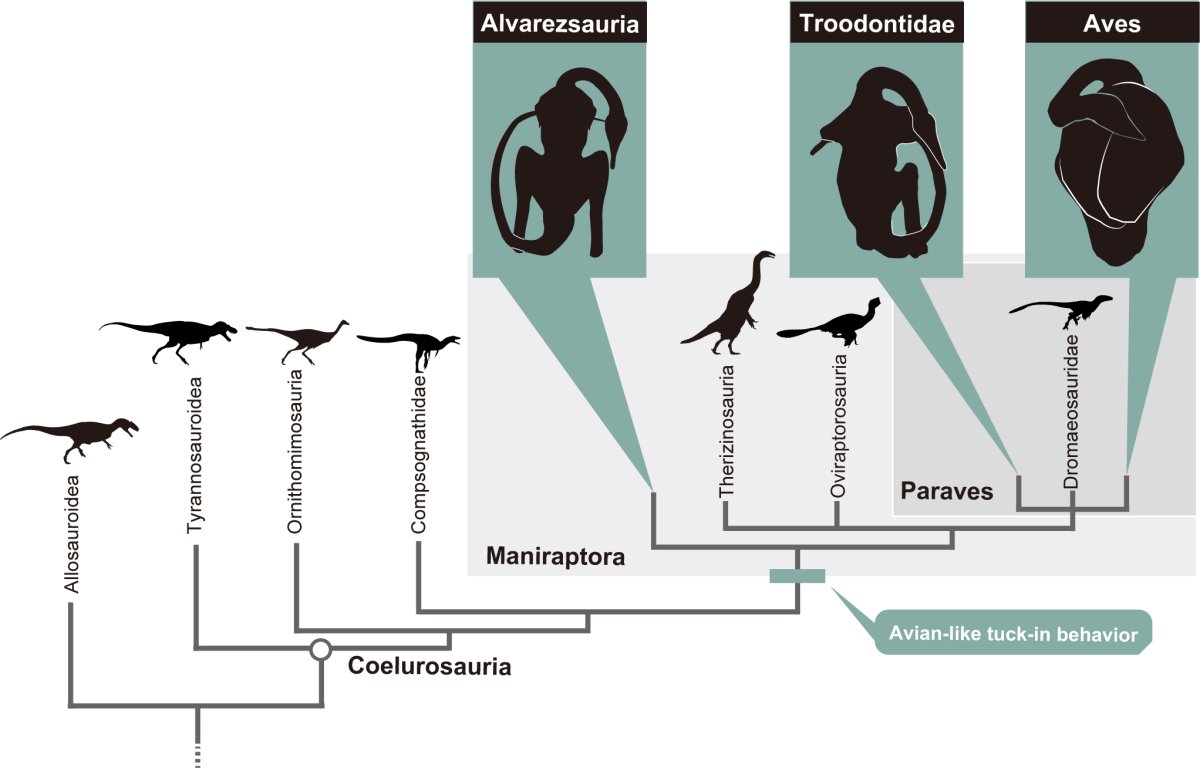

Previously the avian sleeping posture has only been documented in a few specimens of the troodontid dinosaur species Mei long and Sinornithoides youngi—both from China. Troodontids belong to a subgroup of theropod dinosaurs known as the "paravians" that are closely related to birds. In fact, the paravians include the lineages that directly lead to modern birds.

Alvarezsaurids were originally thought to be primitive birds, but now they are classified within the theropod subgroup known as the maniraptorans. These dinosaurs are relatively closely related to birds, albeit more distantly than the paravians. Paravians emerged later than the maniraptorans, diverging from them around 165 million years ago.

"Because troodontids are paravian dinosaurs relatively close to the birds, this behavior in a new alvarezsaurid highlights that the avian-like sleeping behavior originated back to maniraptoran dinosaurs prior to powered flight," Kubo said. "This also provides more evidence that avian characteristics are distributed broadly among avian ancestors."

Jordan Mallon, a paleobiologist with the Canadian Museum of Nature in Ottawa, who was not involved in the latest study, told Newsweek that while this is not the first dinosaur found in a bird-like sleeping posture, it is the first alvarezsaurid known to be preserved in this position.

"[This] suggests that this style of sleeping was more widespread among dinosaurs than we previously suspected," Mallon said. "This adds to an already long and growing list of evidence linking birds to dinosaurs. The bones, the feathers, and even the fossilized behaviors betray the dinosaur-bird connection."

"There's no doubt that this is a fantastic specimen, even apart from the distinctive sleeping posture. At this point, I shouldn't be surprised—the Gobi has yielded many such treasures over the last century."

Ashley Poust, curator of vertebrate paleontology at the University of Nebraska State Museum, who was also not involved in the latest study, told Newsweek the paper was a "fascinating description" of a new theropod from Mongolia.

"The completeness of the specimen also shows that it is posed in a very bird-like posture with its head tucked back by the leg, possibly keeping itself warm," Poust said. "This is really cool—previously a small dinosaur called Mei long has been found in a so-called sleeping posture."

"I worked on the second specimen of Mei long and it's really moving to see such behavior preserved from a Cretaceous animal that otherwise seems so alien. It's important to know that avian behaviors and possibly physiology occur so early in theropod evolution."

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Aristos is a Newsweek science reporter with the London, U.K., bureau. He reports on science and health topics, including; animal, ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.