Loneliness

Why Being Alone Isn't Loneliness

Time spent alone does not at all predict loneliness.

Posted October 2, 2023 Reviewed by Jessica Schrader

Key points

- Psychology distinguishes feeling lonely from being socially isolated, but uses surveys to study both.

- In new research, my colleagues and I sampled sounds of daily life to assess a person's time alone.

- We found that the relationship between being alone and feeling lonely is weak and curved.

Being lonely is a feeling. It’s about feeling disconnected from others, not having the kind of social contact and communion you want with other people. It’s about how you perceive the world around you, and it’s related to your own particular needs and wants.

That means it’s subjective. Some people might want a lot of connection, and feel lonely if they have to spend even a bit of time alone. Others might want less, and only feel lonely when they’re deeply isolated—hardly ever talking to others.

For a long time, psychology has drawn a distinction between being lonely and being alone—but it’s been difficult to measure it precisely. Most previous psychologists have tried to study this distinction using surveys. Asking people about their feelings of loneliness is easy: people are in a good position to report how they feel.

But getting a measure of how alone someone is—or their social isolation, as it is often called in the research literature—is harder. Researchers have asked about how many friends a person has, asked people to remember how much time they’ve spent with others, or asked about how many different groups or communities a person belongs to.

But the gold standard really would be not to rely on what someone is telling you about their time alone, but to be able to observe and measure it ourselves. In a new research paper, my colleagues and I were able to do this.

Measuring how much time people spend alone is hard. How would you do it? Would you just sit around with a pen and clipboard watching what people did all day?

- No, then the person would never be alone.

Would you put up a video camera in their house, work, car, and every other place they are likely to stay?

- You could, but it would be really difficult to make sure you’re capturing their full day, since they might go somewhere new without cameras. Plus, think of all the time you’d have to sit watching video to see if they were alone or not.

The way we ended up capturing time alone was through a sound recorder that the person wore with them throughout the day, over the course of several days. Instead of continuously recording, people just had brief recordings made every 10 or so minutes throughout the day.

Using recording instead of video, and just samples of audio instead of every sound, helped us balance privacy concerns. (Remember how well Google Glasses, which recorded continuously, went over when people wore them in public?)

It also balanced concerns about coding. Every single sound file recorded for our study was coded by hand by a trained research assistant. That’s the best way to make sure you’re getting accurate information about what was recorded—but it also requires a lot of time. Only having to listen to a short snippet every 10 minutes or so throughout the day cuts down on the human effort required. (Note that in another recent paper, we found AI was only around 80 percent accurate in coding talking from this type of sound file. Definitely impressive, but not accurate enough for careful research.)

Actually, this is a method that Matthias Mehl, my former mentor, has been perfecting for years. The Electronically Activated Recorder (EAR) device that he first developed was an audio recorder set up to turn on and off at regular intervals throughout the day. Over the years, it has been developed into a phone app that records and stores sounds on an Android phone.

We typically give research participants a big clunky phone with a hip holster and a caution sign affixed to it, which gives people near our study participants a clue that they’re being recorded. The device allows researchers to follow willing participants (who get a full explanation of how the study will work ahead of time) during their daily life, giving us a window into what they do when they’re not in the lab.

Over the past almost two decades, many studies have used this method to understand human behavior “in the wild.” Our new study of loneliness combined data from several of these previous studies to better assess the amount of time spent alone. (I’ve previously written about how this gives insight into personality—and what behaviors personality traits translate into in daily life.)

In our study, the amount of time a person spends alone was measured by calculating the proportion of files in which a person was talking to someone else. The coding system is careful to distinguish this from a sound file where a person is just in a public place, where other voices can be heard. If there’s talking in the foreground, next to the device, it counts as being with someone. If there’s talking in the background, which might indicate that someone is in an office, coffee shop, or dorm—but not necessarily next to someone—it doesn't count as being with someone. So we ended up measuring whether you spent between 0 and 100 percent of your time alone.

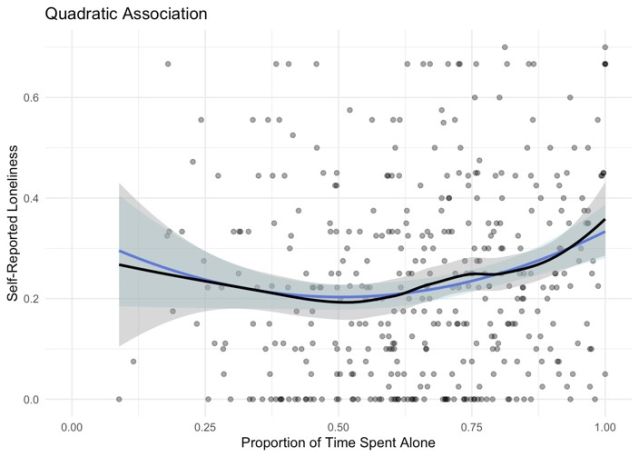

So what’s the big takeaway from all this measurement? The relationship between loneliness and time spent alone is weak and curved.

- It’s weak because knowing how much time spent alone only explained 3 percent of the variation in loneliness. If you know how much time someone spends alone, you wouldn’t be able to predict very well at all how lonely they are.

- It’s curved because more time alone doesn’t just lead to more loneliness in a straightforward way. In fact, people who spend anywhere from 25 to 75 percent of their days alone are all likely to have similarly low levels of loneliness. It’s only at high levels of time spent alone—more than 75 percent—that we expect to see higher levels of loneliness.

- For example, if a person spends 50 percent of their time alone, we’d expect them to rate their loneliness as a 2 out of 10. If they spend 95 percent of their time alone, we’d expect them to rate their loneliness as a 3 out of 10. (Remember—there’s only a weak relationship here!)

So remember: Being alone isn’t the same as feeling lonely, and it’s really only at the extremes of spending time alone that we’d expect people to start feeling more lonely.

Facebook/LinkedIn image: BlueSkyImage/Shutterstock

References

Danvers, A. F., Efinger, L. D., Mehl, M. R., Helm, P. J., Raison, C. L., Polsinelli, A. J., ... & Sbarra, D. A. (2023). Loneliness and Time Alone in Everyday Life: A Descriptive-Exploratory Study of Subjective and Objective Social Isolation. Journal of Research in Personality, 104426.