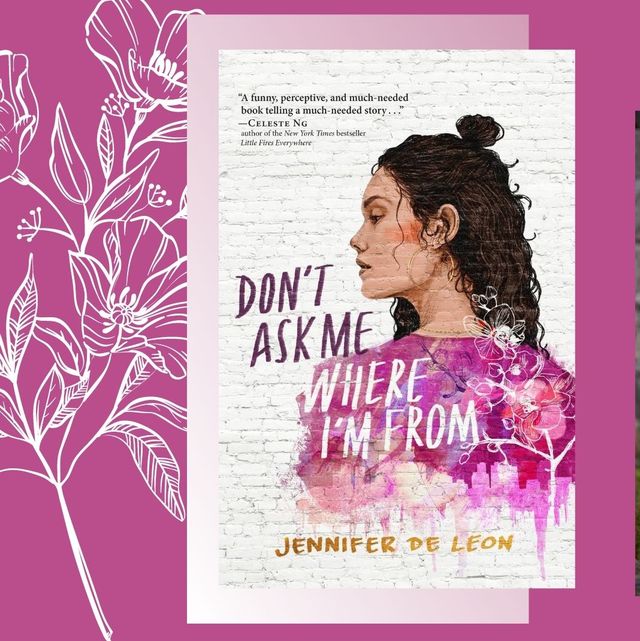

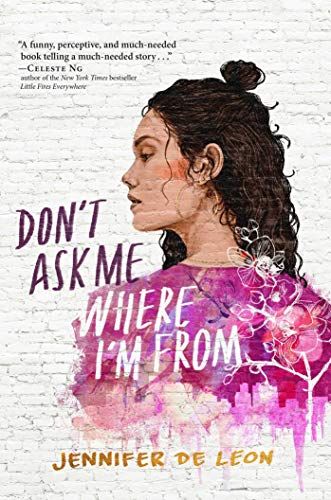

“Don’t ask me where I’m from” is a proclamation the Latinx community is all too familiar with, and it’s also the title of Jennifer De Leon’s debut novel. The book centers on Liliana Cruz, a first-generation Latina teen dealing with major life changes, like transferring to a predominantly white high school and dealing with the disappearance of her father. In the coming-of-age tale, Liliana grows to understand and embrace her bicultural identity and discover her voice as an aspiring writer.

Inspired by De Leon’s experience as a former teacher in Boston Public Schools, Don’t Ask Me Where I’m From deals with racism, immigration politics, code switching, and microaggressions through the lens of a high school teen navigating new experiences at home and school. The story takes place in Liliana’s inner city neighborhood in Boston and Westburg, the wealthy and predominantly white suburban high school she attends due to the city’s Metropolitan Council for Educational Opportunity program, which enrolls thousands of students of color from Boston in predominantly white school districts. It’s through this program that Liliana is exposed to a different way of life that gives her opportunities unavailable to her before but also exposes her to racism and stereotyping from her white classmates.

Born to Guatemalan parents, De Leon grew up not seeing herself reflected in literature and took the opportunity to write the Latina protagonist she yearned to see when she was young. De Leon is also the second author to receive the Walter Dean Myers grant award from We Need Diverse Books (Angie Thomas, author of The Hate U Give, was the first).

Ahead of the release of Don’t Ask Me Where I’m From, Shondaland spoke with De Leon about how her time as a public school teacher influenced her writing, what she has in common with her protagonist, and what was most difficult about writing her novel.

VIRGINIA ISAAD: How did your time as a public school teacher in Boston influence you as you wrote this book?

JENNIFER DE LEON: I can’t imagine having written this book without learning from my students, specifically in Boston Public Schools. As I wrote my many drafts, I heard them in my ear, I could see them walking down the streets of Jamaica Plain as they ate chips and laughed or went on Snapchat. As a teacher I got to know my students on an academic level, certainly, but also on a personal level. Many of them confided in me and they shared their fears and concerns, like a parent in prison or a sister getting pregnant and their joys like a parent coming home from prison, or a sister giving birth to a healthy baby.

VI: Two years ago Massachusetts was named the worst state for Latinos and Boston has the largest population of Latinos in the state. How did Liliana's story highlight their struggles?

JDL: Oh, wow. I did not know Massachusetts had earned that title. I’m not surprised. Boston is an extremely segregated city, as far as racial and economic diversity is concerned. My parents moved to Boston in the 1970s and when I was two years old, they moved the family to a suburb about 30 minutes away in Framingham. Every weekend we spent driving into Boston to visit with my grandmother and tías and tíos and cousins. Monday morning I returned to another reality.

I grew up navigating two worlds, and never quite feeling like I belonged in either. So I wanted Lilliana to experience this code-switching in the book, this kind of moving in between, sometimes from one sentence to the next, and other times literally — from one street to the next. In the novel I wanted to show how there are so many walls, again, literally and figuratively.

I think Boston can be especially difficult for Latinos because it is so spread out, and again, it is so segregated. There is no real “center” in the sense that, oh, Latinos live here and we shop here and we work here. Sure, there are pockets, but in general, it is a lonely place — or can be — if you venture even a bit outside of your neighborhood. So when Liliana does just that — she faces a cold reality that the world is indeed a much bigger, sometimes harsher place than she’d ever known it to be.

VI: The undocumented community is described as living in the shadows and Liliana herself is initially in the dark about her parents’ status. What inspired you to create their backstories and struggles?

JDL: I wanted to tell one true story, even if in fiction. In other words, I wanted to really go a mile deep, not wide, and show how deportation can affect one teen girl, one family. This particular story is not every Latinx girl’s story, nor is it meant to be, and so in writing Liliana’s story I really wanted to add nuance to what may be read as a “single story” in the media, that of a family affected by deportation. In sharing these characters’ backstories and struggles, I hope to give readers more context.

VI: Liliana is her parents’ American dream, in a sense. Can you talk about developing her character as both Latin American and American?

JDL: These are such great questions! Liliana is definitely navigating worlds and identities. For the first time in her life, she is realizing that her story is part of a larger story. Her parents emigrated from Guatemala to Massachusetts. Her grandparents and great grandparents are from Guatemala. She is the first generation in her family to be born in the United States. Seeing herself within this context — again, for the first time — is a powerful moment. I guess that’s why these stories are called coming-of-age.

I wanted to develop Liliana’s character as someone discovering and developing her identity, which includes being Guatemalan and American. I did not want to paint a character who only assimilates — she certainly tries to do just that in the beginning of her journey — but ultimately one who is proud of where she comes from, and if anything, wants to know more and more about her history, all while feeling empowered to pursue multiple opportunities in the United States, including educational opportunity. She doesn’t have to choose.

VI: The racism the METCO students encounter feels like it was taken out of today's headlines, in particular the Black Lives Matter discussions and the ignorance surrounding immigration. What do you hope readers take from the candid conversations in the book?

JDL: I hope readers get a sense of the real conversations teens are often having about race, and that the racist comments and actions by some characters in the book are sobering to some degree, for those in the dark or those living in extreme denial, and as refreshing to other readers. Perhaps for those not used to seeing such candid conversations on the page, even if they know they happen in real life. I also hope that young people, in particular, can see different perspectives because there is a diverse cast of characters here and ultimately, that they will be inspired to act for positive change. We don’t know how many activists are waiting to be fired up and motivated and if it’s one story, one book, one character that can ignite that fire — then I feel my work is done.

VI: You reference Enrique's Journey throughout the book, which details the harrowing journey across the border. What other sources did you draw from as you wrote this book?

JDL: I read a ton — nonfiction, fiction, articles, interviews — including work by Reyna Grande, Francisco Jímenez, and Ted Conover. I also watched documentaries and films, including Which Way Home and Sin Nombre [which followed unaccompanied migrant children]. I spent time interviewing students and teachers in the METCO program as well. In addition, I spoke to family members and consulted my journals from my time living in Guatemala.

VI: Liliana shares how frustrating it is when she's asked where she's from and they also discuss the complexities of Latinidad. What do you wish more people knew about the Latinx community, and what can people do to be better allies?

JDL: I wish people understood that the Latinx community is not a monolithic one. Yes, we share so many commonalities on levels of language, culture, family traditions, etc., but just the same, there are as many differences between someone who identifies as Puerto Rican vs. Mexican vs. Guatemalan vs. Venezuelan, and so on and so forth. I think the best allies are ones who listen and engage and educate themselves and at the same time understand that a Latinx person — especially a first or second or third-generation Latinx person — is not the “expert” on his/her/their culture and is learning as well.

VI: What was the most challenging aspect of writing this book? What has been the most rewarding?

JDL: Most challenging: responding to my mother’s question of, are you done yet? No, seriously. I write about this a lot in my essays/nonfiction, but as a first-generation college graduate and the first writer in the family (as far as I know), I spend much time explaining things, and as any writer knows, writing is hard to explain in terms of traditional parameters such as hours, payment, timelines. Art doesn’t really work that way, and that’s been challenging to explain to my parents. But they are extremely supportive. And so I guess that’s the most rewarding part — knowing that they came to this country 50 years ago and that just one generation later I am able to achieve my dream. That’s crazy and amazing and I don’t take a single drop for granted.

VI: You and your heroine share certain qualities (both of you are Guatemalan writers). How much of this character and her story is autobiographical, and what was it like sharing those parts of yourself especially as young Latina heroines are still uncommon in mainstream literature?

JDL: Yes! I love this question. I could write a memoir in response to this question, but I guess I’ll summarize by saying that I wrote the book I needed as a young person. If I had experienced this “mirror” in literature at a young age, who knows? So I wrote what I hope is a mirror for young Latinas, but then also a window for those working with Latinas — teachers, librarians, mentors, etc.

Liliana and I share so much — we were both born in Jamaica Plain. We both grew up speaking Spanish and English and navigating two different worlds, and often being the only Latinx person in the class. Her father is Guatemalan; my father is Guatemalan. Her mother is Salvadoran, but my mother is also Guatemalan. I grew up in a suburb of Boston, so I was not in the METCO program, but sometimes people mistook me for a METCO student. Both my parents had become U.S. citizens before my sisters and I were born, so deportation did not play a role in our family’s story in the way it does for Liliana. I definitely loved creative writing, as Liliana does. I did not make miniature cardboard houses — wish I had, though!

VI: In the book they discuss six word autobiographies, what would be yours?

JDL: Don’t ask me where I’m from, obviously!

Virginia Isaad is a lifestyle and culture writer based in Los Angeles with bylines in Bustle, Elite Daily, HipLatina, Remezcla, and Mitu. She speaks fluent Spanglish and works to amplify the stories of Latinx communities. Follow her on Twitter @virginiaisaad.

Get Shondaland directly in your inbox: SUBSCRIBE TODAY