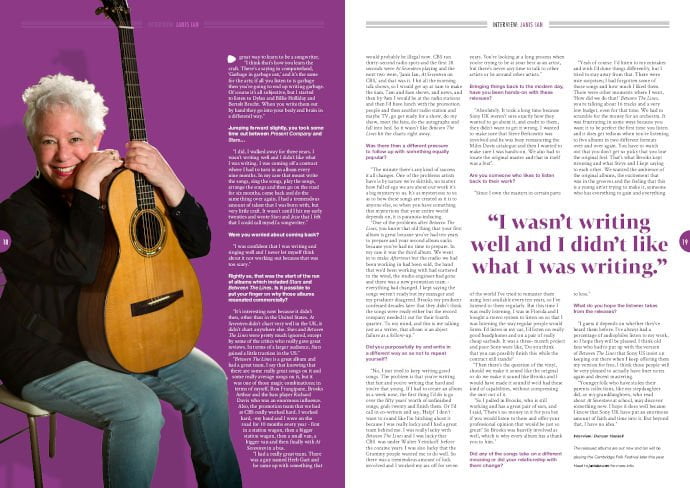

Janis Ian: “It’s as mysterious to us as to how these songs are created as it is to anyone else.” Photo: Peter Cunningham

Between the songs: the iconic NYC-born songwriter reflects on a five-album run which is up there with the very best

From her self-titled 1967 debut through to 2014’s Strictly Solo, Janis Ian’s music has soundtracked our lives for over five decades now. That first album was released when Ian was still a teenager, yet songs such as Society’s Child revealed an ability to channel themes of social awareness into her music that belied her young age. That artistic integrity has been a thread which has continued throughout her career and made her an icon in the eyes of her legions of fans.

Out of all her material though, it’s her run of albums in the mid-to-late 70s which remains the pinnacle of her songwriting. Over five LPs (Stars, Between The Lines, Aftertones, Miracle Row and Night Rains) she established herself as a bona fide star. Tracks like At Seventeen, Jesse and Love Is Blind remain essential listening to this day.

These albums have now been remastered and reissued, giving audiences new and old a chance to hear Ian’s masterpieces once again. They also provide us with a perfect opportunity to revisit that period of her career…

Do you come from a musical family?

“My family are Jewish. Jews of my parents’ and grandparents’ generation tend to use music as a way to gather together, so we were always singing. In addition, my dad went to college after he served in the army; they paid for him to go and he eventually became a music teacher, so there’s a great passion in the family.”

And you wanted to be a songwriter from a very young age?

“I must have only been two-and-a-half when I put together that the sound coming from the piano was being made by my dad, and that was it. It was, ‘That’s what I’m going to do with my life. Forget everything else.’”

Do you remember the first song you ever wrote?

“Oh yeah, Hair Of Spun Gold, which wound up on my first album. I was 12 and I remember it distinctly. I wrote the song and then I sang it for my parents while we were in the car going to visit my grandparents in New York. My mum asked where I’d learnt that song from and I said, ‘I wrote it.’ They both just stopped and looked at me. It had never occurred to me to tell anyone that I had started writing.”

You’re probably not thinking about songwriting as a career when you’re 12…

“I was thinking about getting good grades so my parents would let me go away at weekends and play with my friends, write songs and sing in the Village.”

How much did that Greenwich Village scene inform your early work?

“It was huge. Those were my heroes. To suddenly be on speaking terms with Joan Baez or Tom Paxton, that was amazing. I was 13 the first time I played out at a real gig, I submitted the song to Broadside magazine and they invited me to perform at what was then called ‘The Hootenanny’ in Greenwich Village at the Village Gate, which was normally a jazz club. The owner Art D’Lugoff would donate it once a month to a bunch of folk singers and so there I was on stage with all of these people that I had been listening to for years.

“It was just an amazing group and I did well and then we moved to New York and I fell in with a group of kids who were hanging around with the Reverend Gary Davis. He was blind and he would have his hand on your shoulder and we would lead him around New York. His wife liked me because I loved her chicken. She made the best potted chicken ever. Gary asked if I could open for him at the Gaslight Café when I was 14, when they said no his wife said that he wasn’t feeling well and didn’t think that he’d be able to do the show, and so they said yes. They were pretty amazing.”

Was it the confidence of youth that enabled you to take it all in your stride, or did it feel momentous even back then?

“I don’t know that anything feels momentous at that age, because you’re so busy thinking of the next moment. I mean it was great and amazing but take the Leonard Bernstein special where he featured Society’s Child. I was 15 and didn’t understand the impact of something like that for a long time because I was too busy thinking, ‘Okay, that was really cool but now my maths test is due and I’ve got a gig, what am I going to do?’”

Would you have to carve out specific time for your songwriting in between those studies?

“I started writing poetry as soon as I could write. Really bad poetry, but poetry, and the same with songs. I was always jotting down whenever there was free time. Especially at that age you’re making your bones and learning your trade, I probably played guitar anywhere from two to six hours every single day. I also played piano and so I’d switch back and forth, and I’d write songs and learn other people’s songs. I’d buy a Bob Dylan album and there were never the lyrics, and I couldn’t afford the songbook, so I’d sit down and write out the lyrics.

“That’s a great way to learn to be a songwriter. I think that’s how you learn the craft. There’s a saying in computerland, ‘Garbage in garbage out,’ and it’s the same for the arts; if all you listen to is garbage then you’re going to end up writing garbage. Of course, it’s all subjective, but I started to listen to Dylan and Billie Holliday and Bertolt Brecht. When you write them out by hand they go into your body and brain in a different way.”

Jumping forward slightly, you took some time out between Present Company and Stars…

“I did, I walked away for three years. I wasn’t writing well and I didn’t like what I was writing. I was coming off a contract where I had to turn in an album every nine months. In my case that meant write the songs, sing the songs, play the songs, arrange the songs and then go on the road for six months, come back and do the same thing over again. I had a tremendous amount of talent that I was born with, but very little craft. It wasn’t until I hit my early 20s and wrote Stars and Jesse that I felt that I could call myself a songwriter.”

Were you worried about coming back?

“I was confident that I was writing and singing well and I never let myself think about it not working out because that was too scary.”

Rightly so, that was the start of the run of albums which included Stars and Between The Lines. Is it possible to put your finger on why those albums resonated commercially?

“It’s interesting now because it didn’t then, other than in the United States. At Seventeen didn’t chart very well in the UK, it didn’t chart anywhere else. Stars and Between The Lines were pretty much ignored, except by some of the critics who really gave great reviews. In terms of a larger audience, Stars gained a little traction in the US.”

“Between The Lines is a great album and had a great team. I say that knowing that there are some really great songs on it and some really average songs on it, but it was one of those magic combinations; in terms of myself, Ron Frangipane, Brooks Arthur and the bass player Richard Davis who was an enormous influence. Also, the promotion team that we had at CBS really worked hard. I worked hard, -my band and I were on the road for 10 months every year – first in a station wagon, then a bigger station wagon, then a small van, a bigger van and then finally with At Seventeen in a bus.

“I had a really great team. There was a guy named Herb Gart and he came up with something that thirty-second radio spots and the first 28 seconds were At Seventeen playing and the next two were, ‘Janis Ian, At Seventeen on CBS,’ and that was it. I hit all the morning talk shows, so I would get up at 5am to make the 6am, 7am and 8am shows, and news, and then by 9am I would be at the radio stations and then I’d have lunch with the promotion people and then another radio station and maybe TV, go get ready for a show, do my show, meet the fans, do the autographs and fall into bed. So it wasn’t like Between The Lines hit the charts right away.”

Was there then a different pressure to follow up with something equally popular?

“The minute there’s any kind of success it all changes. One of the problems artists have is by nature we’re skittish, no matter how full of ego we are about our work it’s a big mystery to us. It’s as mysterious to us as to how these songs are created as it is to anyone else, so when you have something that mysterious that your entire world depends on, it is paranoia-inducing.

“One of the problems after Between The Lines, you know that old thing that your first album is great because you’ve had ten years to prepare and your second album sucks because you’ve had no time to prepare. In my case it was the third album. We went in to make Aftertones but the studio we had been working in had been sold, the band that we’d been working with had scattered to the wind, the studio engineer had gone and there was a new promotion team – everything had changed.

“I kept saying the songs weren’t ready but my manager and my producer disagreed. Brooks my producer confessed decades later that they didn’t think the songs were ready either but the record company needed it out for their fourth quarter. To my mind, and this is me talking just as a writer, that album is an abject failure as a follow-up.”

Did you purposefully try and write in a different way so as not to repeat yourself?

“No, I just tried to keep writing good songs. The problem is that you’re writing that fast and you’re writing that hard and you’re that young. If I had to create an album in a week now, the first thing I’d do is go over the fifty years’ worth of unfinished songs, grab twenty and finish them. Or I’d call in co-writers and say, ‘Help!’ I don’t want to sound like I’m bitching about it because I was really lucky and I had a great team behind me.

“I was really lucky with Between The Lines and I was lucky that CBS was under Walter Yetnikoff before the cocaine years. I was also lucky that the Grammy people wanted me to do well. So there was a tremendous amount of luck involved and I worked my ass off for seven years. You’re looking at a long process when you’re trying to be at your best as an artist, but there’s never any time to talk to other artists or be around other artists.”

Bringing things back to the modern day, have you been hands-on with these reissues?

“Absolutely. It took a long time because Sony UK weren’t sure exactly how they wanted to go about it, and credit to them, they didn’t want to get it wrong. I wanted to make sure that Steve Berkowitz was involved and he was busy remastering the Miles Davis catalogue and then I wanted to make sure I was hands-on. We also had to locate the original master and that in itself was a feat.”

Are you someone who likes to listen back to their work?

“Since I own the masters in certain parts of the world I’ve tried to remaster them using best available every ten years, so I’ve listened to them regularly. But this time I was really listening. I was in Florida and I bought a stereo system to listen on so that I was listening the way regular people would listen. I’d listen in my car, I’d listen on really good headphones and on a pair of really cheap earbuds. It was a three- month project and poor Sony were like, ‘Do you think that you can possibly finish this while the contract still stands?’

“Then there’s the question of the vinyl, should we make it sound like the original or do we make it sound like Brooks and I would have made it sound if we’d had these kinds of capabilities, without compressing the snot out of it.

“So I pulled in Brooks, who is still working and has a great pair of ears, and I said, ‘There’s no money in it for you but if you would listen to these and offer your professional opinion that would be just so great!’ So Brooks was heavily involved as well, which is why every album has a thank you to him.”

Did any of the songs take on a different meaning or did your relationship with them change?

“Yeah of course. I’d listen to my mistakes and wish I’d done things differently, but I tried to stay away from that. There were nice surprises; I had forgotten some of those songs and how much I liked them. There were other moments where I went, ‘How did we do that?’ Between The Lines, you’re talking about 16 tracks and a very low budget, even for that time.

“We had to scramble for the money for an orchestra. It was frustrating in some ways because you want it to be perfect the first time you listen and it does get tedious when you’re listening to five albums in two different formats over and over again. You have to watch out that you don’t get so picky that you lose the original feel. That’s what Brooks kept stressing and what Steve and I kept saying to each other.

“We wanted the ambience of the original albums, the excitement that was in the grooves and the feeling that this is a young artist trying to make it, someone who has everything to gain and everything to lose.”

What do you hope the listener takes from the releases?

“I guess it depends on whether they’ve heard them before. I’ve always had a percentage of audiophiles listen to my work, so I hope they will be pleased. I think old fans who had to put up with the version of Between The Lines that Sony US insist on keeping out there when I keep offering them my version for free, I think those people will be very pleased to actually have liner notes again and decent mastering.

“Younger folk who have stolen their parents’ collections, like my stepdaughter did, or my granddaughters, who read about At Seventeen at school, may discover something new. I hope it does well because I know that Sony UK have put an enormous amount of faith and time into it. But beyond that, I have no idea.”

Interview: Duncan Haskell

![Songwriting Credits… best new music playlist [May 2024]](https://www.songwritingmagazine.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/songwriting-credits-may-2024-335x256.jpg)

Related Articles