'I Expected to Have a Day Job for the Rest of My Life'

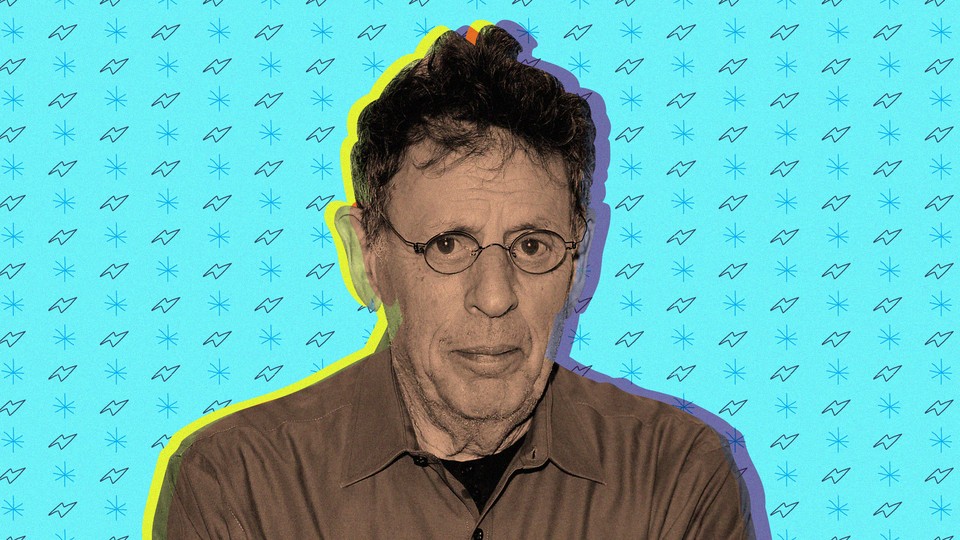

How Philip Glass went from driving taxis to becoming one of the most celebrated composers of our time

At age 12, Philip Glass started working in a Baltimore record store owned by a man he called Ben. Ben was, in fact, Glass’s father, but he and his brother, Marty, both referred to him by his first name because they didn’t want anyone to know they were his children. Of course everyone still knew who they were.

Even before working in that small record store and spending countless evenings with Ben, learning to sort the good music from the bad, Glass knew he’d become a musician. He took flute lessons; his brother studied the piano. Now 81 years old, Glass is one of the most lauded composers of the 20th century. He has an honorary doctorate in music from his alma mater, the Juilliard School, and has won a National Medal of Arts, the Society of Composers and Lyricists’ Lifetime Achievement Award, and multiple Golden Globe and Academy Awards. I spoke with him about those early days in his father’s record store, the scariest moments from his time driving taxis in New York City to make ends meet, and how young people today should seek jobs that grant them independence.

This interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

Lolade Fadulu: You got into music because of your father, but did you ever consider becoming a librarian like your mother?

Philip Glass: My mother was a teacher and a librarian, and I definitely was not going to become a librarian. I knew these two people very well, my mother and father, and I had no interest in my mother’s friends at all. I was very interested in everything that my father did. That was just the way it turned out for me.

My mother, on the other hand, she encouraged my brother Marty, and Sheppie, my sister, so we all were given music lessons when we were young. That was considered part of our education. Isn’t that wonderful? I’m talking about the 1940s. If you were a young person, there might not be a program in the school that you went to, but my brother and sister had private music lessons, and I went to the Peabody Conservatory when I was, I think, 8 years old.

I wanted to have two instruments, but I was only allowed to have one because that was the budget that we had. So what I did is I would sit in on my brother’s lessons. He had a teacher that came to the house. The teacher would give him a lesson and would leave. And as soon as he left I went over and I played the lesson. My brother thought that I was teasing him, and he would chase me around the room. We were kids, really young. And he thought I was making fun of him. But I wasn’t. I just wanted to play the piano. He’d say, “Well, you have your own lessons. You don’t have to steal mine.” But I did have to steal his, actually.

We were very good friends. He passed away last year. But, you know, he was in his 80s. I’m into my 80s. So he had a wonderful life of his own. He wasn’t a musician.

Fadulu: You were interested in everything your father did. What did he do?

Glass: He had a small record shop in downtown Baltimore. Now, you have to remember in the 1940s we didn’t have big Virgin Megastores or Sam Goody record shops. We didn’t have a music store like that. It was like a mom-and-pop candy store. In the back of the store he fixed radios, and in the front of the store he sold records.

He himself was not a musician, but he loved music, and he would bring music home to listen to. If he didn’t sell a record he would try to find out what was wrong with the music and he would take it home and listen to it. And I was listening. I was his listening partner. The things he’d listen to were mostly modern music that people didn’t like, and we both ended up liking all of this modern music. He became an expert on modern music. I’m talking about modern music of the ’40s, so that’s people like Bartók and Hindemith and people like that.

In the record store we had all kinds of music. We had country and western music, we had jazz music, we had band music, we had marching-band music, we had classical music, we had operas. But there were only two categories, really. That was good music and bad music. That’s the only thing he recognized. He would encourage people to buy the pieces that he liked.

My brother and I spent all our weekends and the holidays at the record store starting from the age of 12. So he introduced me to a lot of music, my father did. He passed away in the 1970s. I dedicated my first violin concerto to him because I thought he would have liked if he had lived to hear it, and so I always felt that violin concerto was written for him.

Fadulu: Did you work in your dad’s record store at all?

Glass: Oh, yes. Oh yes, yes, yes, yes. From the age of 12. It wasn’t considered child labor. It was a family business. At the beginning, all my brother and I did were the inventories, and we moved the records around. But we eventually got to know the business pretty well.

To this day, among my earliest memories was someone would give my father $5 and he’d hand them a record. So the exchange of money for art, I thought that was normal. I thought that’s what everybody did. I never thought there was anything wrong about making money.

Fadulu: Did your dad expect you to take over the store at some point?

Glass: No, he never expected that. He loved the store himself.

It was just a small store but he eventually got a partner who had a radio program on the Baltimore stations. And suddenly his record store began. I remember coming and seeing him one time when I came back from school, and I said, “Ben.” (We always called our father by his first name because my brother and I didn’t want people to think that we were working for our father.) And I said, “Ben, you’re really doing well here now.” I was about 18. And he said, “Yeah.” He said, “Store’s going good.” “Well,” I said, “all of those years of hard work paid off.” And he said, “Nope. Just got lucky.” He was that kind of a guy.

Fadulu: Did you have any doubts about becoming a musician?

Glass: I always knew I was going to do music, so I had no doubts about it at all.

The only issue was how I was going to get a music education in Baltimore. Well, I was lucky, again, because the Peabody Conservatory was quite a good music school. I went away to college when I was quite young, and I went to the University of Chicago. In those days you could enter the university if you passed the entrance exam. I told my advisor I wanted to take the entrance exam for Chicago, and he thought that was a funny idea. Everyone thought it was funny. But me, I was pretty serious. I took the test and I passed it, to everyone’s surprise.

At the same time Chicago was the center for the jazz movement, especially for the bebop players and people like Charlie Parker and Charles Mingus and Bud Powell. They were regular players in Chicago, and I got to hear them, too. I was a little too young to go into the bars. They didn’t let me go in the bars, but there was a bar on 57th Street on the South Side of Chicago. And I would stand outside listening to the music, and finally the guy at the door said, “Hey, kid, come on. You can come and sit here. Sit here for listening, but you can’t drink anything. Just sit here and you can listen.” I used to go down there and listen to jazz.

Fadulu: While you were really getting started, you worked as a plumber and as a taxi driver, and also as part of a moving company. Why did you work those jobs?

Glass: I had an ensemble at the time. I would go out and play for three weeks. We would come back from the tour, and we usually had lost money so I had to make money immediately. I put an ad in the paper. My cousin and I ran the company, and I moved furniture for about three or four or five weeks. Then I went on tour again. Again, we lost money.

That went on for years. I thought it was going to go on for the rest of my life, actually. It never occurred to me that I would be able to make a living, really, from writing music. That happened kind of by accident.

I was interested in jobs that were part-time, where I had a lot of independence, where I could work when I wanted to. I wasn’t interested in working in an office where everything would be very regimented.

About that time—I’m talking about the early ’70s—the part of New York called SoHo now, it was mostly buildings that housed factories that made clothing. But about this time, artists were buying spaces in that area, and my cousin and I began to help build. We were putting in heating systems and putting in kitchens and bathrooms. We learned how to do that. We would put an ad in the paper, and we’d get to your house, and we’d do it. When it was time to go back on tour, I just closed up for about three weeks and [would] come back and go to work again for two or three months sometimes.

Also, at that time, I was a composer in residence at the La MaMa theater on East Fourth Street, so I was also writing music for plays, and I had my ensemble. I was starting to become a professional composer. I had been out of Juilliard by that time. And eventually, by the time I was 41, 42, I was actually making a living playing music.

I was surprised it happened so quickly, actually. I expected to have a day job for the rest of my life.

Fadulu: I feel like composers are viewed a lot differently than plumbers and taxi drivers.

Glass: Let me tell you something. If you’re in New York City, you might hail a cab. There’s a good chance that the driver would be an actor or a performer. A lot of day jobs around New York are picked up by people in the arts. It was very common to find that the waiter at the coffee shop you went to was having a concert later in the week and you would be invited to come to the concert. So my experience was quite different from what you’re describing. A lot of people in theater, in dance, in filmmaking and music performance, we all had day jobs. And eventually if you were lucky you spent more time doing your art than making a living.

Fadulu: Did you like driving taxis?

Glass: I loved it, actually.

I would pick up a car, usually around 5 o’clock in the afternoon, and I would drive till one or two in the morning, and I would get up early in the morning, actually to take my kids to school, because I had kids growing up in New York at the time. And sometimes I would stay up all through the night, write music, then take the kids to school. Then I would go to sleep around 8 or 9 o’clock and I would wake up around 4 o’clock and go back to the garage or wherever I was going. So I could combine a workday and a regular writing schedule at the same time.

It was very scary at times. Robberies could happen. Unpleasant things can happen when you pick up people off the street, which is what taxi drivers do all the time. It wasn’t so great in one way, but I got to know the city. I knew my way around the Bronx, my way around Brooklyn. And I could listen to music on the radio. There was always a good music station to listen to.

I liked the independence of having a car in New York and just driving around. It could get tiresome, especially on the holidays when there could be very long workdays. But I didn’t want to be in a place where there was a boss telling me what to do.

Fadulu: What were some of the scariest times?

Glass: I remember a couple of guys get in the car laughing their heads off, and they’re throwing money around. They just robbed a store, right?

Now they’re in the back of my car. I said, “Where are you going?” They said, “We’re going to Bed-Stuy.” Well, at that time it was one of the most hardcore places in New York for people out of work and looking for money and this and that. These guys had just robbed a store and looked to me like they were just about to rob me, too.

If I was lucky I could get rid of them somehow. Sometimes a police car would follow us for a while and they’d pull me over and take a look at the guys in the car and say, “What are you doing with these guys?” Well, you know, as a cab driver you’re supposed to pick up anybody. You have to. And I said, “Look, I just want to get out of here.” And the cop car would follow me until I let them off.

I could tell you a lot of very scary stories. But mostly, evenings were pretty quiet, just picking up people. Sometimes they had drunk too much and you’d have difficulties of that kind, and then they forgot where they lived or they got sick in the car. It’s not a violence-free environment, to be driving a cab in New York at night. I was glad when it was over.

I was commissioned to write Satyagraha, an opera about Gandhi, and the opera company paid me. So I didn’t go back to work for four or five months, and then after that I had another job. About a year later I realized I hadn’t driven a cab in a year. I renewed my cab license for another year or so, but I never had to drive again. By that time I was 42 years old. And that was 40 years ago, so that’s a long time ago.

Fadulu: Was there anything that you learned while you were driving that was helpful for composing?

Glass: I learned a lot. I listened to music on the radio. There were a few good music stations.

In those days you could work three days a week, maybe four sometimes, and you could live on that. It was the quickest and easiest way to make an honest living. I thought it was a pretty good deal. I didn’t have to teach any classes anywhere. I just drove the car and I got paid. I liked that. I had my independence, which was very important to me. But also, it didn’t take much time.

But, look, the thing to remember is that life was financially much easier. Actually, for the young people trying to make a living today, part-time, it’s almost impossible.

People work six days a week. No one can work three days a week. It’s just gotten to be more expensive, the rents are higher, there are more people around trying to do exactly what you’re trying to do. When people ask me how I did it, I say to the young people, “Look, I have to tell you. It was much easier when I did it.” I said, “It’s hard right now.” But people are still coming to the city, to the big cities where you have concert halls and museums and galleries. There’s a lot of part-time work. There are all kinds of things that you can do.

I went to school for a long time. I finished my studies when I was 28. Was probably much too late. But no one ever asked to see my diplomas. Never. When I got a job writing music no one said, “Can I see your diploma first?” That never happened. It makes you laugh when you think about it. There’s a lot to be learned at school, but it doesn’t give you a passport to making a living at all.

Fadulu: Do you think people should still follow those passions, especially if they’re in the arts?

Glass: When I do concerts I often give talks to students. They get them together, and I talk to them in the afternoon, and we talk about music. Not too long ago one young fellow, he said, “Tell me one thing that I can take away from this talk that I’ll remember and that’s important.” And I said, “No, I’ll give you one word.” He said, “What’s that?” I said, “Independence.”

Fadulu: Yeah, you have said that a lot. Why was having your independence when it came to work so important?

Glass: Well, it meant that I controlled how I spent my time. Being a young dancer, a young painter, a tremendous amount of dedication and work goes into developing the skills to accomplish the artistic goals that you set for yourself. I’ve had friends who’ve gone to law school, and one of them will go and complain about how hard they worked, and I just laugh at them. None of them would consider practicing six or eight hours a day, but that’s quite normal for dancers or musicians or painters. Our workdays tend to be more like eight to 10 hours a day, and we don’t take weekends off, and very few people take off holidays. It’s a very work-intensive environment. But the freedom of working that way seems to be preferable.