Milli Vanilli, Pop Music's Original Fakes

Twenty-five years ago, the lip-syncing models were dethroned—and a class of more sophisticatedly manufactured stars took their place.

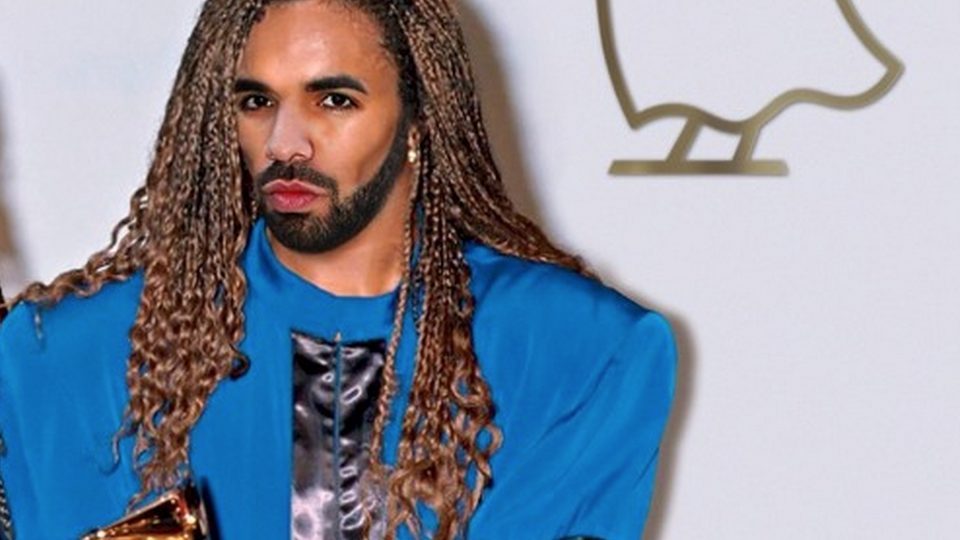

One of the stranger images in pop culture this year has been the one above, of Drake’s face pasted onto the body of a Milli Vanilli member. It came courtesy of Meek Mill, the rapper who picked a fight on Twitter over the summer by claiming that Drake doesn’t write his own songs. In one of the diss tracks to result, Mill (nickname: “Meek Milli!”) called Drake a “Milli Vanilli-ass n*****.” T-Pain, commenting on the controversy, boiled it down to being a “Milli Vanilli thing.”

Among the many important implications of this headline-making beef is the notion that, despite or perhaps because of the best efforts of some of pop culture’s watchdog forces, Milli Vanilli hasn’t been forgotten. November 27 marks a quarter century since the Grammys revoked the Best New Artist trophy from the act whose songs, it turned out, were sung not by the European models Fab Morvan and Rob Pilatus but by uncredited musicians working with the producer Frank Farian. It’s one of the most important scandals in pop history, especially when viewed in the context of today’s cultural wars over realness and fakeness.

Morvan and Pilatus always maintained that they were suckered by Farian, who recruited them for their looks and presented them with a catchy demo track that they, despite his promises, were never given a chance to rerecord. As that track, “Girl You Know It’s True,” rose to the top of the charts internationally, the two became sensations who gyrated (with great finesse and charisma) for screaming masses. In one spectacularly ill-advised quote, they told a Time reporter that they were more talented than Bob Dylan or Paul McCartney. A backing-track malfunction at a show fed rumors that they were just lip syncing, but it all really began to unravel when a singer named Charles Shaw said that he was the real voice on “Girl You Know It’s True,” after which Farian owned up about what he’d created.

The response from the public and the music industry was furious. Class-action lawsuits were filed, with a resulting court settlement allowing consumers to seek refunds for their Milli Vanilli merch. Said a 9-year-old former fan quoted in the L.A. Times in 1990, “I think they’re dirty scumbuckets.” Said the president of the Recording Academy upon the revocation of the Grammy, “I hope this revocation will make the industry think long and hard before anyone ever tries to pull something like this again.” Rob Pilatus died of an overdose in 1998, shortly after the Behind the Music special about the band aired.

As far as the public knows, no one has quite tried to “pull something like this again,” if “this” means “drastically lying in liner notes and publicity about the provenance of hit songs.” But Milli Vanilli’s influence is a bit counterintuitive: Their fall from stardom presaged more artifice in pop, not less. In his recent book The Song Machine, John Seabrook details the complex, well-funded apparatus of songwriters and producers and executives who mint most pop songs these days, an apparatus that isn’t hidden from listeners but is also not fully understood by most of them. The system in part has its roots in the work of Lou Pearlman, the now-incarcerated entrepreneur who assembled the Backstreet Boys after witnessing the backlashes to Milli Vanilli and New Kids on the Block—backlashes that were both rooted in the idea that talentless people were lying about being talented. According to Seabrook, “Pearlman wondered what an urban-sounding group of five white boys who really could sing might do in the marketplace.”

130 million records sold later, we have an answer. It’s not often appreciated that a core part of the appeal of the Backstreet Boys—and the other boy bands that followed, some also managed by Pearlman—was that its members really could sing. These teenagers, brought together by newspaper ads to wiggle in CGI videos to songs written by Swedish studio pros, were positioned as a more “authentic” alternative to the likes of Milli Vanilli. Which puts a pretty fine point on what a shell game authenticity can be. Today, autotune is everywhere, producers spend hours “comping” vocals (i.e. piecing together the very best syllables out of dozens of takes), and the Backstreet Boys songwriter Max Martin has nearly as many No. 1 hits as the Beatles.

None of this is a secret. For members of the public still subscribing to the idea that musical merit should be connected to natural musical ability, vocal prowess is often the saving grace, the exonerating factor, that lets them enjoy many of the slickest acts working today. It is essential to the myth of One Direction, for example, that they have verified pipes, that they were generated from a talent contest. Lady Gaga, whose shtick parodies and embraces the insane fakeness of pop, is often praised because she “really can sing.” Or think about what sets Adele apart: She uses many of the same songwriters as the rest of Top 40—Max Martin’s on 25—but she sells more in large part because of how she belts. Morvan and Pilatus didn’t have the fig leaf of vocal talent to protect them once the provenance of their music became clear. But the songs they fronted were as undeniably catchy—if saccharine, over-earnest, cheesy—as they were before the ruse was up.

As for Drake, he seems to have weathered the accusations of Milli-Vanilli-ness just fine. He’s a rapper and a singer, and his delivery—sometimes cocky, sometimes smooth, often sounding unlike much else on the radio—is undeniably his. Plus he can make the case that he’s been honest about the authorship of his work. Quentin Miller, the man Mill said wrote some of Drake’s best recent bars, is credited on a few Drake songs (but not all of the ones at issue). And hip-hop has been collaborative since the days when Easy-E was recording Ice Cube lyrics. “If I have to be the vessel for this conversation to be brought up—you know, God forbid we start talking about writing and references and who takes what from where—I’m OK with it being me,” Drake said recently about Mill’s ghostwriting accusations. The conversation that he was talking about has included incensed radio rants and profane diss tracks, but it’s still been less brutal than the reckoning that faced Milli Vanilli.