The Strangest True-Crime Story Yet

The new Netflix documentary Abducted in Plain Sight is a bewildering account of one girl’s kidnapping by a family friend.

One of the scenes in Abducted in Plain Sight that best encapsulates the strangeness of its story comes midway through, after the second time a teenager named Jan Broberg has been kidnapped by a close family friend. That friend, Robert Berchtold, calls Jan’s mother, Mary Ann, and falsely tells her that Jan is prostituting herself and selling drugs. “Oh my goodness,” Mary Ann replies, in a steady, even tone, as if he’s just told her that seasonal allergies might be worse than usual this summer, or that two people brought potato salads to the potluck. “Oh dear. Oh. Now I won’t be able to sleep.”

Abducted in Plain Sight was first released as a documentary in 2017 with the title Forever ‘B,’ but it’s gained rather more traction this month after being added to Netflix’s true-crime library. Over the past week, viral tweets and Reddit threads and various expressions of incomprehension have batted around the internet, as viewers try to make sense of what exactly they’ve just watched. Much of the outrage targets Jan’s parents, who participated fully in the documentary, and whose behavior in response to Berchtold’s prolonged abuse of their daughter strikes many viewers as shockingly inadequate at best. Jan—now Jan Broberg Felt, an actor who’s appeared in Criminal Minds and Everwood—has subsequently defended her mother and father.

Manipulation and grooming are not understood by so many. It happened to my whole family, this man was a master and my parents saved my life. They’re the bravest people I know, willing to try to help the rest of you see what they didn't. That is the only reason we told our story.

— Jan Broberg (@janbroberg) February 4, 2019

Part of the problem is that Abducted in Plain Sight, a 90-minute movie in a field populated mostly with six- or eight-hour series, is focused entirely on telling a story rather than illuminating it. It unpacks too many bizarre events in a short time frame to allow for much additional analysis. And the Broberg family, confessional to a fault, are primed more for honesty than for self-inspection. The result is a documentary that exposes them for public scrutiny without pausing to really interrogate their actions.

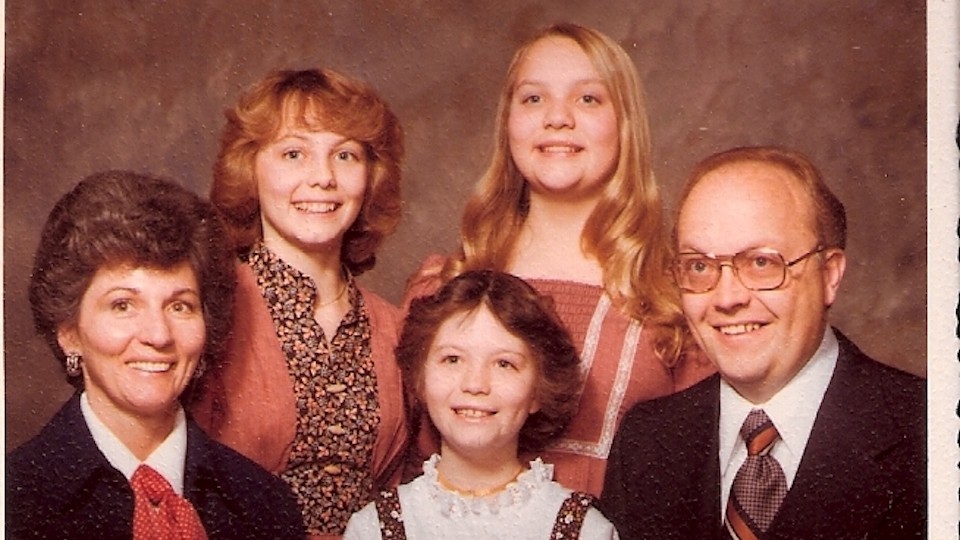

Directed by Skye Borgman, Abducted in Plain Sight begins in the early 1970s in Pocatello, Idaho. Jan was one of three daughters born to Bob Broberg, a florist, and Mary Ann. After becoming fast friends with a new family called the Berchtolds, the Brobergs noticed that the charismatic “fun dad” Robert Berchtold (known as “B”) seemed overly interested in Jan. “He was like a second father to me,” Jan explains, before detailing her memories of how he drugged and molested her. The movie includes pictures Berchtold took of Jan as a 12-year-old girl, all straw-colored hair, wide eyes, and freckles. In one, her underwear is clearly visible.

In October 1974, Berchtold offered to pick Jan up from her piano lesson and take her horseback riding. He never brought her home. The details that follow spiral quickly from strange to appalling. The Brobergs were going to call the police until Gail Berchtold, Robert’s wife, asked them not to. Jan’s family waited several days before notifying the FBI, and even after doing so were reluctant to accept that Robert Berchtold had actually done anything wrong. Pete Welsh, the lead FBI agent investigating Jan’s disappearance, had to “drill that into our minds,” Mary Ann explains in an interview. “He kidnapped her. She’s your daughter. She’s gone.”

The Brobergs’ relative calm in the face of their 12-year-old daughter’s abduction by an adult man is one of the most immediately disturbing elements of the story. Other revelations, though, come thick and fast. Berchtold, it transpires, had repeatedly tried to infiltrate other families with young girls, and had been reprimanded by the high council in his church, the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints, for doing so. He convinced Bob and Mary Ann that his subsequent treatment by a psychologist involved spending multiple nights in bed with Jan. “Neither one of us was comfortable with him doing it,” Mary Ann says, “but it was his therapy.”

The parental behavior that Mary Ann and Bob freely confess to in Abducted in Plain Sight is so bewilderingly naive that the more salacious and peculiar events Borgman goes on to lay out are almost hard to grasp. Without spoiling the most shocking ones, they involve multiple confessions of extramarital sexual relationships, as well as an elaborate plot involving aliens that Berchtold used to prey on Jan. Berchtold was arrested for kidnapping, but the Brobergs, under duress, withdrew their most serious charges. Berchtold was sentenced to five years in prison anyway but served only 10 days. Bob and Mary Ann, Agent Welsh states, were told to cut off communication with the Berchtolds. Which he adds, emphatically, “They. Did. Not. Do.”

Here is where Borgman’s unwillingness or lack of space to parse exactly what’s going on feels most acute. A few people in the movie vaguely assert that it was the 1970s, and no one really understood what pedophiles were, or that intimate friends and family members could also present a real danger to children. “We never called ’em pedophiles; I’m sure it was in the dictionary someplace,” Agent Welsh says. And yet several local families had been troubled enough by Berchtold’s attempts to get close to their children that the church intervened. People knew, or certainly had surmised, that he was a threat. Faith leaders knew. The Brobergs seemingly knew. Nonetheless Berchtold, even after his conviction and his briefest of interludes in prison, was able not only to be around children, but also to purchase and run a “family-fun center” as a business.

In particular, the fact that the Berchtolds and the Brobergs were all part of the same faith community seems to merit more analysis than it receives. So does a legal system that allowed Berchtold to kidnap, drug, and rape a child and receive a virtual slap on the wrist. The film implies that the Broberg parents were both brainwashed and manipulated by Berchtold, which accounts for some of their actions, but not nearly all. Karen Campbell, one of Jan’s sisters, comes closest to analyzing what happened when she posits that her parents are simply experts in denial. That’s why, she says, “they didn’t probe more when they knew something had happened. They didn’t want to know. It’s too painful for them to realize that they allowed that to happen to her.”

For viewers watching at home, though, judging the Brobergs is easier, even if it’s hard to ever feel fully informed, or to believe that the family knew what they were getting into by airing everything so publicly. The hope for Abducted in Plain Sight, Borgman and Jan Broberg Felt have both said, is that it helps end the culture of silence around sexual abuse and assault. The reality, though, is that the extraordinary nature of the revelations in the film, and their insufficient excavation, end up overshadowing the much more urgent subject at hand.