Recently, the novelist, critic and one-time philosophy professor William H Gass was asked by Publishers Weekly for five writing tips. His advice contained the following sentence: “Be happy because no one is seeing what you do, no one is listening to you, no one really cares what may be achieved, but sometimes accidents happen and beauty is born.”

I like to imagine the Knopf publicist who negotiated this assignment for Gass banging a head against a solid surface, in reply to such a despairing marketplace self-assessment. And yet anyone who publishes Gass probably already knows his thinking about mass taste. In his 1983 essay Tropes of the Text, Gass wrote that “only the common run of novels expects the one-night stand”. Gass himself belongs to the class of writers – in that essay he cites Gertrude Stein, Thomas Bernhard and Mario Vargas Llosa as fellow travellers – whose less-common fictions demand more of their audiences (and justify longer, more committed relationships).

Whether you consider him the last modernist or one of the postmodernists, you can’t deny the fundamentally tricky nature of Gass’s fiction. Characters tend to develop strangely (or not at all); settings are sometimes created from a fusillade of petty-seeming details that can collectively avoid a straightforward accounting of the basic proscenium stage of action. Though what can pull you through – especially during a mystifying first reading – is the rhythmic verve of Gass’s sentences.

David Foster Wallace, citing Gass’s 1966 debut, Omensetter’s Luck, as one of the “direly underappreciated” American novels of the late 20th century, commended Gass’s prose for being “bleak but gorgeous, like light through ice”. But in that same brief entry, Wallace hit on another attribute of Gass’s, which is the author’s humor. Omensetter’s main character is a “cityish” priest; not long after being appointed to a post in a rural setting – and in the midst of a banquet held in the priest’s honor – Gass gives the character a multi-page internal monologue rife with details of the bash’s unappetizing menu and a hurried trip to a bathroom, which includes the line: “The body of Our Saviour shat but Our Saviour shat not.”

Gass’s penchant for creating witty grouches and solipsists capable of charm can be seen, at the paragraph level, as a rebellion against the sentimentality of mainstream fiction. He has described the historical turn toward “realism” as the act of pulling “fiction up from its roots in Rabelais and Cervantes”, in order to spirit novels “away into the bourgeois world like so much else”. In an era during which most other storytelling mediums are working overtime to ingratiate via what the New Yorker’s Rebecca Mead calls “the scourge of ‘relatability’”, Gass’s refusal to play on the sympathies we assume for ourselves can feel like a welcome change-up.

But Gass is not content merely to tweak the bourgeois modern reader. On a macro level, the author’s obsession with crimes against humanity has a starker (and more judgmental) political cast. The height of this form of protest was his long-in-process book The Tunnel – a 1996 novel about a historian of the Nazis who freely admits to an unseemly identification with the Third Reich. And even when one of Gass’s moral offenders gets what’s coming to him, as in the finale of the story “Emma Enters a Sentence of Elizabeth Bishop’s” (which Gass says has “a feminist strain”), the vengeance doesn’t wholly vitiate the foregoing ugliness, either. “I’m resisting in the sense that I’m yelling about it,” Gass once said in an interview. “My anger comes from still thinking it might be … remedied, that it isn’t just: ‘Well, that’s the way it is,’ and sort of resigned to it.”

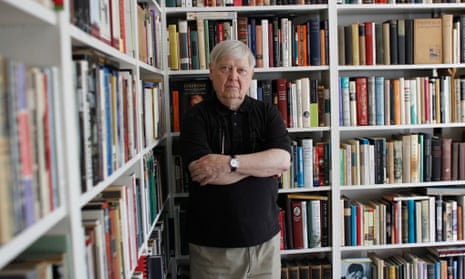

At 91 years of age, Gass remains anything but accepting of our world as it is. By being fleeter and more seductively plotted than The Tunnel, his 2013 novel Middle C managed to top it as a savage exploration of moral failure. And Gass’s new collection shows the author continuing his late-career roll. Except for its final, never-before-seen story, Eyes: Novellas and Stories scoops up the shorter fictions that Gass placed in literary journals during the same period he was composing Middle C. The first novella, titled “In Camera”, shares some similarities with that book – the most notable attribute being a viciously insular aesthete protagonist who articulates a critical distance from the rest of humanity through his studied curation of a private museum.

Early in the novella, we’re told that this proprietor of a photographic print shop accepts responsibility for a child beset by a host of physical challenges – and who was recently abandoned by his mother (the aesthete’s former wife). Was the aesthete the original father? (In classic Gass fashion, the welfare agency sounds oddly equivocal.) From there, the story is intent on shredding the ideal of familial affection entirely. Over the course of some years, the aesthete progresses from calling his charge “hey you, stupid” to, eventually, “Mr. Stu.” (So he’s not the traditional, nurturing father figure.)

And yet the aesthete manages to pass on what appears to be some family values. (Black and white prints are obviously truthful, while color prints are condemned as too eager to be loved.) Mr Stu gradually comes to understand that his surrogate father might not have come by all of his prized, rare black and white prints honestly. And though (spoiler alert) Mr Stu cannot keep the police from arriving and carting away his father’s stolen goods, the boy can create something of a miracle send-off, by massaging the light that the world casts into this dingy cavern devoted to photographic refinement. (Being dimly lit, the shop itself suggests the interior of a camera body – its rusty, exterior metal shutters an amateur’s aperture.)

Before his dad trudges off to jail, the faint flicker that touches the back of the shop makes for the most thoughtful going away present imaginable. It would be too much to call this emotionally resonant fillip a saving grace – as there’s very little salvation in Gass’s fiction – though the isolated moment of grace is firmly there, claiming its circumscribed place in the world. Elsewhere in this collection, in the novella “Charity”, Gass again treads through the grim psychology of a selfish-seeming protagonist, before at last giving us an understanding (if not precisely an excuse) for his brittle mode of being.

While the remaining, shorter stories in Eyes are more akin to exercises, they generally have a playful air that mixes well with Gass’s customary grouchiness – as with “Don’t Even Try, Sam” (which is narrated by what turns out to be the casually racist prop piano used in the film Casablanca). Finally, though, the big draw in Eyes is the one-two punch of novellas that opens the collection – both of which linger in the mind with greater force than the works in his Tunnel-era collection, Cartesian Sonata and Other Novellas. Taken together with Middle C, the novellas in Eyes show that, for all of Gass’s expertise with the tropes of his favored texts, he’s still stumbling over some new accidents of beauty too.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion