2008-10 - Extra Aircraft

2008-10 - Extra Aircraft

2008-10 - Extra Aircraft

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

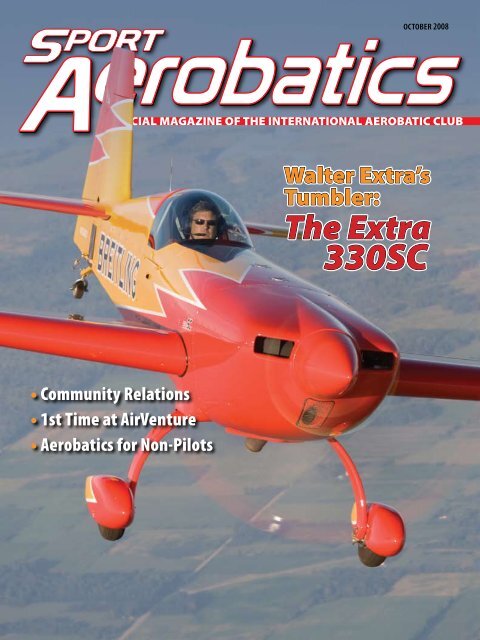

OCTOBER <strong>2008</strong><br />

OFFICIAL MAGAZINE OF THE INTERNATIONAL AEROBATIC CLUB<br />

• Community Relations<br />

• 1st Time at AirVenture<br />

• Aerobatics for Non-Pilots<br />

Walter <strong>Extra</strong>’s<br />

Tumbler:<br />

The <strong>Extra</strong><br />

330SC

Bonnie Kratz<br />

The <strong>Extra</strong><br />

300SC<br />

Walter <strong>Extra</strong>’s New Unlimited Contender<br />

Budd Davisson<br />

At the pointy end of the aerobatic totem pole—the Unlimited category—winning is<br />

measured in micro-points, and this week’s killer competition airplane is next week’s<br />

also-ran. It’s an increasingly brutal arena in which the dance steps demanded by the<br />

choreographer would leave old Count Aresti breathless with astonishment. And it doesn’t appear<br />

likely that the trend toward extreme performance from both the airplane and the pilot will let up<br />

anytime soon.<br />

The recent drive to design aircraft that clearly outdistance the pack has forged a razor-edged<br />

competition between the various airplanes that are expected to successfully compete (read that<br />

as “win”) in Unlimited competition. At the same time, an unlikely market has developed just<br />

outside of competition in which pilots who have the wherewithal to own the most recognized,<br />

butt-kicking aerobatic bird will buy one just like their hero flies even though they have no<br />

intention of ever competing in it. It is this group that actually forms a market base wide enough<br />

to support the development of a new airplane, and it is a market Walter <strong>Extra</strong>, he of<br />

the airplanes of the same name, knows well. He has created a small empire<br />

by understanding that, if he builds a winning airplane flown by<br />

well-known champions, he will sell many more of the<br />

nearly identical airplane to serious pilots<br />

who just want to own the best<br />

aircraft available.<br />

6 • OCTOBER <strong>2008</strong> SPORT AEROBATICS • 7

The <strong>Extra</strong> 330SC is a definite departure from previous designs. The small canopy and redesigned tail are noticeable changes.<br />

The operative word in the foregoing equation is “winning<br />

airplane.” He knows well that the adoration<br />

and financial attention will quickly shift focus once<br />

one design has been eclipsed by another. It wasn’t until<br />

his airplanes began to lose favor, and Kramer Upchurch<br />

of Southeast Aero in St. Augustine, Florida, and champion<br />

competitor and air show performer Mike Goulian laid<br />

it on the line to him, that he took up the challenge to<br />

update his <strong>Extra</strong> 300 series.<br />

“Walter is an extremely creative guy,” Upchurch says.<br />

“But the company was focused on their corporate aircraft,<br />

the 400 and 500, and the 300S began to lose ground to<br />

the CAP 232 and the Edge 540. Serious competition pilots<br />

always buy the very best there is, and quite a number of<br />

top-level pilots left the <strong>Extra</strong> for a CAP or Edge.”<br />

Upchurch and Goulian visited <strong>Extra</strong> in 2005, and Walter,<br />

himself a winning competition pilot, responded by<br />

diving into his 300S, working down the items that were<br />

on the Upchurch/Goulian wish list.<br />

Pilots such as Mike Goulian had flown and competed<br />

in just about all of the existing Unlimited airplanes, and<br />

there was a wide consensus of opinion that the 300S was<br />

still a fine airplane. But if it was going to win Unlimited,<br />

some areas had to be addressed.<br />

“Everyone wanted more roll rate,” Upchurch says,<br />

“which, considering that it already rolled at 330-350<br />

degrees per second, shows just how demanding the competition<br />

market has become. However, it was more than<br />

just roll rate the pilots were looking for. They wanted the<br />

airplane to have more all-around maneuvering capabilities,<br />

particularly at lower airspeeds in the 60-knot range.”<br />

“Pilots also wanted more vertical performance,” says<br />

Upchurch, “which sounds a little crazy considering how<br />

far it would go vertical already, but there were airplanes<br />

with more vertical performance, so, if Walter wanted to<br />

keep selling airplanes, his had to go higher for longer and<br />

still be rolling well when coming to a stop at the top.”<br />

The competition guys were, in point of fact, becoming<br />

just a little spoiled and a tad blasé. With airplanes such<br />

as the Edge, Sukhoi, CAP, and <strong>Extra</strong>, the performance bar<br />

had been raised so high that incremental improvements<br />

were going to come slowly to an airplane such as an <strong>Extra</strong><br />

300S, but they expected it and they were willing to pay<br />

for it. And then the air show and freestyle parameters<br />

were stirred into the mix.<br />

Kramer points out another wish list item that’s new to<br />

this generation of aerobatic pilots.<br />

“The ability to tumble easily, predictably, and for longer<br />

periods of time has become an issue in recent years,”<br />

says Upchurch. “Where in the past any tumbling maneuver<br />

was just a novelty, they are now an aerobatic staple,<br />

and pilots—and audiences—expect them. Walter had to<br />

redesign his tail to make the airplane more aggressive in<br />

the way it tumbled.”<br />

The concept of intentionally tumbling an airplane isn’t<br />

something that’s taught in aerodynamic classes. Not even<br />

in graduate school. In fact, tumbling is the antithesis of<br />

what an aeronautical engineer strives for. He wants smooth<br />

flow, stable handling, and, until very recently, couldn’t<br />

computer-model (or even imagine) what the forces were—<br />

and where they went—in an airplane that was being made<br />

to act in a dynamic fashion that was anything other than<br />

aerodynamic: Tumbling often reverses the forces on the<br />

airframe but in ways that still aren’t totally understood.<br />

Plus, a traditional engineer is going to have next to no<br />

experience—practical or theoretical—in what you have to<br />

design into an airplane to make it better at tumbling.<br />

Much of what the engineering community knows<br />

about tumbling is empirical: Pilots figured out how to<br />

tumble the airplane in various ways and, when they broke<br />

something, the engineers had another data point to work<br />

with, which helped them in their design work. However,<br />

there aren’t many engineering types out there like Walter<br />

<strong>Extra</strong> who can tumble an airplane with the best of<br />

them. He came at the tumbling problem, as well as the<br />

other wish list improvements, from an entirely different<br />

perspective: He, more than most tech types, understood<br />

exactly what the market was saying it wanted and knew<br />

how to deliver it.<br />

Walter had lots of ideas about how to attack the wish<br />

list, but central to everything was improving the powerto-weight<br />

ratio. That meant more motor and less weight.<br />

He had already begun using the AEIO-580 with 330 hp<br />

on tap. However, to put the horsepower to work in the<br />

Bonnie Kratz<br />

330SC, as the new design was called, he used a new prop<br />

from MT that was specifically designed to give more lowspeed<br />

thrust. It had fatter, wider blades that were more<br />

efficient at putting the ponies on tap to work.<br />

“When it comes to weight,” says Upchirch, “Walter is<br />

fond of saying you lose it a gram at a time rather than<br />

pounds and kilos. But in this case, the grams removed<br />

total up to nearly 150 pounds lower than a 300S.”<br />

When shaving weight off of an aerobatic airplane, you<br />

don’t just start using smaller this and lighter that. It must<br />

be done while keeping the ultimate strength in mind at<br />

all times. Nothing can be compromised. In the case of<br />

the 330SC’s evolution from the 300S, the weight came off<br />

through the use of technology and careful planning. All<br />

push-pull tubes in the control system, for instance, are<br />

carbon fiber. The same carbon fiber concept is used on the<br />

wing ribs: Where once they were plywood, they are now<br />

carbon fiber. The firewall was lightened using titanium.<br />

The final airframe is rated at plus-and-minus <strong>10</strong> Gs, but<br />

loads to destruction show its limit actually exceeds 24Gs.<br />

Everywhere you look in the airframe there are new, stateof-the-art<br />

components.<br />

The roll rate issue was tackled in a very non-<strong>Extra</strong> sort<br />

of way. The ailerons are hinged so that, when deflected<br />

past a certain amount, the leading edges protrude a sizable<br />

distance above or below the wing. In so doing, to<br />

those of us in the cheap seats, it appears that rather than<br />

acting like regular ailerons that generate lift by changing<br />

the camber of the wing, these create a slot effect. At large<br />

deflections, this effect makes the aileron act as if it is a<br />

separate surface that generates lift on its own, independent<br />

of the wing. This is probably where the increased roll<br />

rate (430-450 degrees per second) gets its start.<br />

Although the new trapezoidal planform of the ailerons<br />

has to be pointed out to be noticeable, the unusual shape<br />

also helps in the roll rate department. Rather than being<br />

rectangular, as is traditional, the tips are quite a bit wider<br />

than the roots. It’s our guess that by moving the center<br />

of pressure of the aileron outboard, it gains leverage and<br />

can, with less effort, more quickly move the wing. It’s also<br />

worth noting that there isn’t even a hint of an aileron<br />

shovel to be seen, although Upchurch indicated that for<br />

European Aviation Safety Agency certifications, the shovels<br />

will go back on.<br />

An even more subtle change is seen in the taper of the<br />

wing. At the tip, the chord is much shorter, which, when<br />

combined with the new aileron, achieves the desired roll<br />

performance.<br />

The art of tumbling is one thing. The art of figuring<br />

out how to make an airplane flop end over end in a more<br />

predictable manner has to be something of a black art, part<br />

of which includes making the airplane snap outside better.<br />

This Walter knew how to do, but some of those changes,<br />

notably the new horizontal tail, helped in both areas.<br />

He went to slightly thinner airfoil sections with less radius<br />

on the nose. This made them more critical, so he could<br />

get them to stall more predictably. The span is shorter and<br />

the elevator balances are noticeably different.<br />

Continued on page 12<br />

8 • OCTOBER <strong>2008</strong> SPORT AEROBATICS • 9<br />

Photos by Budd Davisson and Craig VanderKolk<br />

From nose to tail, the new <strong>Extra</strong><br />

330SC incorporates changes<br />

that make it lighter and more<br />

maneuverable. Mechanically<br />

adjustable foot pedals and carbon<br />

fiber push rods save weight, while<br />

trapezoidal ailerons and new<br />

geometry on the tail improve rolling<br />

and tumbling maneuvers.

“<strong>Extra</strong> <strong>Extra</strong>! Read All About It!”<br />

OnE MAn’S OPInIOn OF THE ExTRA 330SC<br />

Carl Pascarell<br />

Doug Vayda, chief pilot for Southeast Aero, launched me in<br />

the SC with uncharacteristically subdued advice: “Don’t<br />

have too much fun and don’t hurt yourself too badly.”<br />

When you first approach the airplane, you get a sense of its<br />

performance while still 50 feet away. Simply put…big motor,<br />

little airframe. This is no doubt gonna be a monster. But no ogre<br />

this—oh no. The ’580 is so elegantly cowled, the rest of the airplane<br />

just seems to flow back from it. The fit and finish are firstclass,<br />

consistent with the established <strong>Extra</strong> tradition. This particular<br />

SC, with its Mirco Pecorari custom-designed paint scheme,<br />

dripped with performance potential and raw sex appeal.<br />

Entering the cockpit is typically <strong>Extra</strong>: foot step on fuselage,<br />

stand up on seat, and wiggle your feet forward under the instrument<br />

panel and onto the rudders. Rudders on the SC are not<br />

electrically adjustable as on the other <strong>Extra</strong>s. (Remember the<br />

weight thing?) Fortunately, the seat is three-way adjustable,<br />

allowing Patty Wagstaff-sized pilots as well as Doug Vayda-sized<br />

pilots an easy fit given two minutes and a couple of “pull pin”<br />

seat adjustments. To me (5 feet <strong>10</strong> inches, 180 pounds), the<br />

cockpit felt just about perfect: a definite “wearing the airplane”<br />

sort of impression without feeling cramped or jammed and just<br />

enough headroom to allow for the “negative G” stretch.<br />

Several “consumable” but less than ideal ergonomic features<br />

were noted, however. For instance, when at idle, the throttle is<br />

located too far aft to reach easily. A bit awkward initially, but<br />

once the throttle is advanced at all, this ceases to be a factor.<br />

Secondly, the aileron push-pull tubes pass directly under the<br />

pilot’s knees/calves and actually rub against those areas when<br />

the stick is pushed side to side. This is an issue for most averagesized<br />

individuals. Having said that, when in flight and particularly<br />

during maneuvering, it is scarcely noticeable and presents<br />

no impediment to control feel or response.<br />

Finally, there is an electric pitch trim toggle switch located on<br />

the upper instrument panel. It’s not convenient, and Doug assures<br />

me that on this and future examples the trim will be relocated to<br />

the stick, as with military fighters. Fortunately, because the airplane<br />

flies as if balanced close to the “neutral point,” very little trim is<br />

required throughout the normal range of speeds. Still, I would prefer<br />

good old-fashioned manual trim in an airplane like this.<br />

Engine start is straightforward and welcomes you with a<br />

jumping rumble under the hood reminiscent of a top fueler<br />

“nitro idling” on the starting line. The big ’580, with its six-intoone<br />

exhaust, sends pulses of power through the airframe and<br />

into your body, adding to the airplane’s already formidable<br />

presence. The taxi to the runway was expeditious in part due<br />

to the wide-blade MT dragging me along but also because of<br />

my eagerness to get airborne and explore this thoroughbred’s<br />

awesome capabilities. The wind was light and variable with the<br />

temperature at 79 degrees, and the airplane was loaded with<br />

full “aerobatic” fuel: 25 gallons and empty wings.<br />

Take-off acceleration was consistent with the current crop of<br />

high-powered competition machines, which is to say…exhilarating.<br />

I let the airplane fly off tail low and rotated to a truly<br />

ridiculous attitude in an attempt to hold what I figured was the<br />

best angle. Passing through 1,000 feet 14 seconds after liftoff—<br />

that’s right, 14 seconds—I turned west out of the pattern only<br />

to realize I was still only halfway down the runway! As you<br />

might imagine, 3,000 feet came pretty quickly, and the flight to<br />

the practice area was 190-knots quick.<br />

I have to admit, my initial impression was that the ailerons<br />

were heavier than I would have preferred. The very next flight<br />

I changed my mind. It was as if the ailerons got lighter. They<br />

didn’t, of course, and upon reflection I think my sense of what I<br />

expected the airplane to be may have colored my assessment.<br />

I decided further that the airplane is meant to be flown aggressively.<br />

When flown as such, the roll axis seems just about right.<br />

In fact, the more aggressively one flies the airplane the more<br />

harmonized the controls seem.<br />

Roll accelerations are extraordinarily high, generating rates in<br />

excess of 440 degrees per second with virtually no ramp-up. It’s<br />

like…Move aileron…Get roll….Right now! Here’s the kicker. A lot<br />

of airplanes roll like crazy. It’s not that tough a thing to get them<br />

to do, but not all of them can be well controlled. Frankly, this<br />

has been an issue for me with many of the <strong>Extra</strong>s I’ve flown. The<br />

ailerons are just too “bobbly” for my liking: no real center and, on<br />

some, an almost negative stick force gradient that makes precise<br />

roll control a chore until you get used to them. Well, fear not. The<br />

SC has set a new standard of roll control and authority for the<br />

<strong>Extra</strong>s. In fact, with the possible exception of the old ’230, it has<br />

the finest ailerons of any existing <strong>Extra</strong>. Crisp stops and lightningfast<br />

starts are well controlled with very little practice. Four-point<br />

rolls up, down, or anywhere in between are a head-banging,<br />

gear-shaking, bang, bang, bang, bang affair. Would I like them to<br />

be a bit lighter? Probably, but I’m likely just being picky.<br />

Overall, I felt the airplane’s basic handling qualities were<br />

pretty well managed. Stick forces in pitch were fairly light.<br />

Somewhat lighter pulling than pushing, but that suits me just<br />

fine. Things such as rolling turns suffer just a bit because of it,<br />

but only at first. The difference, as they say in test pilot parlance,<br />

is “consumable”—that is, adequately manageable.<br />

Snap rolls are quick and precise. Inside or out, up or down, single<br />

or multiple. This, I confess, I gleaned from watching the pros fly.<br />

Champions Patty Wagstaff and David Martin, each with virtually no<br />

time in the airplane, were snapping it as well as anything they’ve<br />

flown—as much a testament to their ability as the airplane’s.<br />

The subtleties of snap rolls and rollers are one thing, but to<br />

me, the truly impressive nature of the airplane is evident in the<br />

“wow” maneuvers. You know the “wow” maneuvers—<strong>10</strong>-roll<br />

torque rolls, double and triple nose-over-tail tumbles, knifeedge<br />

spins that you can barely hold onto, and tiny “micro loops”<br />

at 60 knots. These are the “YEE HA!” things that make the airplane<br />

so exhilarating and so memorable.<br />

Having quickly gained confidence in the SC, my second flight<br />

was in the low-altitude practice box at the St. Augustine Airport<br />

in Florida. My flight was a chaotic mass (or mess as some would<br />

have it) of one-after-the-other, body-punishing attempts to do<br />

all I could in 20 minutes.<br />

Vertical performance was exceptional, and I’m almost embarrassed<br />

to admit I actually pulled power from time to time to<br />

stay down in the box and keep from exceeding the 3,500-foot<br />

box ceiling and/or the 220 knot redline. now that’s precisely the<br />

type of problem I enjoy having in an airplane. I particularly liked<br />

the stability the airplane exhibited when stuck in the vertical. It<br />

was almost as if the airplane was flying with an “attitude hold”<br />

engaged. Once stuck there, very little attention was required to<br />

maintain the vertical. This was in part due to the low, off-speed<br />

trim requirement and was generally true for all lines and angles.<br />

I tended to concentrate on vertical and point maneuvers if<br />

for no other reason than they are so well done by the SC. Vertical<br />

four points up, inside, outside, inside triple vertical eights<br />

or “snowmen,” and the “how long is this gonna go on” torque<br />

rolls were pushing me over the “too much fun limit” Doug had<br />

warned me about.<br />

All high-alpha maneuvering was as well behaved and controllable<br />

as any aerobatic plane I’ve flown, the “micro loops”<br />

in particular. Starting at 60 knots and flown in full buffet with<br />

almost full aft stick, the roll and yaw axis throughout the loop<br />

were completely controllable with conventional control input,<br />

so much so that from the ground it was not apparent any buffet<br />

existed at all.<br />

All maneuvers were thrilling to say the least, but it was the<br />

knife-edge spins that captured my attention more than any<br />

other maneuver. Entry into the “knife” from a hammerhead was<br />

easily accomplished, even when the hammerhead pivot was<br />

sloppily flown. The pitch rate from the onset was eye-popping<br />

and almost beyond my ability to adequately hang onto. Three<br />

turns was the most I could hang onto, and even at that, I landed<br />

with the G-meter pegged on the negative end.<br />

My 20 minutes were up in short order and, taxiing back after<br />

landing, I recalled again what Doug had said about having too<br />

much fun. I knew what he meant. And I didn’t listen. With -+9Gs<br />

and -6 Gs on the meter, I dragged myself out of the airplane<br />

sweaty, bruised, and exhausted, huffing and puffing as if I’d just<br />

run 5 miles. I’m no stranger to high performance and generally<br />

not easily impressed, but man was that fun! It’s going to<br />

be interesting to see how the airplane’s future develops in the<br />

hands of true competition professionals.<br />

<strong>10</strong> • OCTOBER <strong>2008</strong> SPORT AEROBATICS • 11

Continued from page 9<br />

At the same time that <strong>Extra</strong> was looking for better performance,<br />

he also included some changes that gave the<br />

airplane greater utility. Specifically, the aerobatic header<br />

tank is now 26.7 gallons, which is almost twice what it<br />

used to be. Inasmuch as there can be no fuel in the wing<br />

tanks while doing hard aerobatics, that used to make the<br />

trip to the practice area and back a little dicey. The bigger<br />

aerobatic tank also adds a modicum of safety and peace<br />

of mind to aerobatic practice. There are 31 gallons in the<br />

wings, giving a total of 57 gallons usable, which gives a<br />

solid three hours of cruise at more than 190 mph with a<br />

wide reserve margin.<br />

AEROBATICS<br />

Basic through Unlimited<br />

Competition & Sport<br />

Safety & Proficiency<br />

Basic & Advanced Spins<br />

12 • OCTOBER <strong>2008</strong><br />

Pitts S-2B<br />

Super Decathlon<br />

Citabria<br />

MAINTENANCE<br />

FACILITIES<br />

We specialize in<br />

Fabric<br />

Tailwheel<br />

Aerobatic <strong>Aircraft</strong> Repair<br />

Owned and operated by Debbie Rihn-Harvey<br />

Is the 330SC the perfect airplane and is Walter happy<br />

with it? Probably not. No designer is ever totally happy<br />

with the final product, especially since an airplane is<br />

nothing but a bunch of compromises from the beginning.<br />

That’s the character of the beast. However, what is important<br />

is whether the competition community is happy with<br />

the changes that have been made and whether the airplane<br />

can regain its crown. The jury is still out on that score, and<br />

we’re at the end of the competition season. The debate will<br />

have to wait until spring to be settled. With all the new<br />

hardware showing up in the box, the coming competition<br />

season promises to be the most exciting ever.<br />

Featuring ratchet seatbelt system<br />

Hooker Custom Harness<br />

324 E. Stephenson St.<br />

Freeport, Illinois 6<strong>10</strong>32<br />

Phone: (815) 233-5478<br />

FAX: (815) 233-5479<br />

E-Mail: info@hookerharness.com<br />

www.hookerharness.com<br />

— Dealer for Strong Parachutes —<br />

Bonnie Kratz