Burrard Inlet Environmental Indicators Report - the BIEAP and ...

Burrard Inlet Environmental Indicators Report - the BIEAP and ...

Burrard Inlet Environmental Indicators Report - the BIEAP and ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

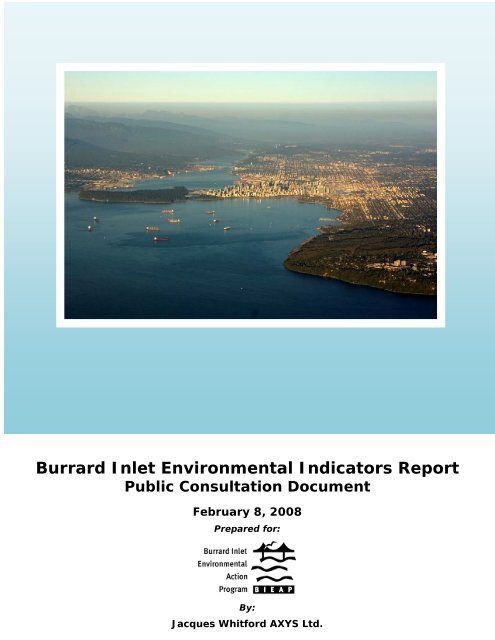

<strong>Burrard</strong> <strong>Inlet</strong> <strong>Environmental</strong> <strong>Indicators</strong> <strong>Report</strong><br />

Public Consultation Document<br />

February 8, 2008<br />

Prepared for:<br />

By:<br />

Jacques Whitford AXYS Ltd.

Public Input<br />

Public input is important to <strong>the</strong> <strong>BIEAP</strong> <strong>and</strong> its partner agencies. For fur<strong>the</strong>r information about<br />

public consultation opportunities surrounding this document, or to order any of our<br />

publications, please contact us at:<br />

<strong>Burrard</strong> <strong>Inlet</strong> <strong>Environmental</strong> Action Program (<strong>BIEAP</strong>)<br />

501-5945 Kathleen Avenue,<br />

Burnaby, BC<br />

V5H 4J7<br />

Tel: 604-775-5756<br />

Fax: 604-775-5198<br />

e-mail: mail@bieapfremp.org<br />

Visit our website at www.bieapfremp.org<br />

“A thriving port <strong>and</strong> urban community co-existing within a healthy environment”<br />

<strong>BIEAP</strong>’s overall vision for <strong>Burrard</strong> <strong>Inlet</strong><br />

Citation: Jacques Whitford AXYS Ltd. 2008. <strong>Burrard</strong> <strong>Inlet</strong> <strong>Environmental</strong> <strong>Indicators</strong><br />

<strong>Report</strong>: Public Consultation Document. <strong>Report</strong> prepared for <strong>Burrard</strong> <strong>Inlet</strong><br />

<strong>Environmental</strong> Action Program, Burnaby BC by Jacques Whitford AXYS Ltd.<br />

Burnaby BC. February 2008. 47 pp.

<strong>Burrard</strong> <strong>Inlet</strong> <strong>Environmental</strong> <strong>Indicators</strong> <strong>Report</strong> February 2008<br />

Acknowledgements<br />

The Plan Implementation Committee of <strong>BIEAP</strong> has guided development of <strong>the</strong> environmental<br />

indicators approach over several years. Core members of <strong>the</strong> Committee are:<br />

Ken Ashley, Metro Vancouver<br />

Juergen Baumann, Vancouver Port Authority<br />

Ken Bennett, District of North Vancouver<br />

Darrell Desjardin (chair), Vancouver Port Authority<br />

Robyn McLean, Environment Canada<br />

Brent Moore, BC Ministry of Environment<br />

Brian Naito, Fisheries <strong>and</strong> Oceans Canada<br />

<strong>BIEAP</strong> program staff include:<br />

Michelle Gaudry<br />

Daria Hasselmann<br />

Anna Ma<strong>the</strong>wson<br />

Many people <strong>and</strong> agencies assisted <strong>the</strong> Committee by providing data, reviewing reports,<br />

providing guidance on indicator development, <strong>and</strong> in several cases developing <strong>the</strong> indicators.<br />

These include <strong>the</strong> following:<br />

BC Ministry of Environment<br />

Chris Dalley<br />

Liz Freyman<br />

Diane Su<strong>the</strong>rl<strong>and</strong><br />

Les Swain<br />

Cindy Walsh<br />

Bird Studies Canada<br />

Peter Davidson<br />

Caslys Consulting Ltd.<br />

Ann Blyth<br />

City of Port Moody<br />

Julie Pavey<br />

City of Vancouver<br />

Don Brynildson<br />

Andrew Ling<br />

David Desrochers<br />

Environment Canada<br />

Greg Ambrozic<br />

Wendy Avis<br />

Rob Butler<br />

John Elliott<br />

Andrew Green<br />

Deanna Lee<br />

Gevan Mattu<br />

John Pasternak<br />

Bill Taylor<br />

Cecilia Wong<br />

Metro Vancouver<br />

Nimet Alibhai<br />

Jim Armstrong<br />

Stan Bertold<br />

Dianna Colnett<br />

Terry Hoff<br />

Derek Jennejohn<br />

Andrew Marr<br />

Roger Quan<br />

Ken Reid<br />

Shelina Sidi<br />

John Swalby<br />

Albert van Roodselaar<br />

Post Consumer Pharmaceutical<br />

Stewardship Association<br />

Ginette Vanasse<br />

UBC Co-op Program<br />

Hea<strong>the</strong>r Brekke<br />

Vancouver Port Authority<br />

Christine Rigby<br />

Westcam Consulting Services<br />

Mike Preston<br />

Yarnell & Associates<br />

Patrick Yarnell<br />

ESSA Technologies Ltd. evaluated potential environmental indicators <strong>and</strong> prepared <strong>the</strong><br />

baseline datasets for <strong>the</strong> Plan Implementation Committee.<br />

Jacques Whitford AXYS Ltd. prepared this consultation document.<br />

Page | i

<strong>Burrard</strong> <strong>Inlet</strong> <strong>Environmental</strong> <strong>Indicators</strong> <strong>Report</strong> February 2008<br />

This page left blank intentionally

<strong>Burrard</strong> <strong>Inlet</strong> <strong>Environmental</strong> <strong>Indicators</strong> <strong>Report</strong> February 2008<br />

Table of Contents<br />

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .......................................................................................................... i<br />

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................................... 1<br />

PART 1 – SETTING THE CONTEXT ........................................................................................ 3<br />

PART 2 – LINKS BETWEEN HUMAN ACTIVITIES AND BURRARD INLET STATUS........... 8<br />

PART 3 – THE INDICATORS.................................................................................................. 11<br />

1. Tree Canopy Cover ....................................................................................... 12<br />

2. Parks <strong>and</strong> Protected Areas.............................................................................. 1<br />

3. Waterbird Abundance.................................................................................... 20<br />

4. Air Quality...................................................................................................... 23<br />

5. Greenhouse Gas Emissions.......................................................................... 23<br />

6. Water <strong>and</strong> Sediment Quality.......................................................................... 23<br />

7. Recreational Water Quality, Fecal Coliforms................................................. 23<br />

PART 4 – REFERENCES........................................................................................................ 40<br />

PART 5 – GLOSSARY ............................................................................................................ 43<br />

List of Tables<br />

Table 1: Key Findings <strong>and</strong> Trends for <strong>Burrard</strong> <strong>Inlet</strong> <strong>Environmental</strong> <strong>Indicators</strong>.................... 2<br />

Table 2: <strong>BIEAP</strong> Partners <strong>and</strong> Communities Bordering <strong>Burrard</strong> <strong>Inlet</strong>................................... 3<br />

Table 3: <strong>Burrard</strong> <strong>Inlet</strong> <strong>Environmental</strong> <strong>Indicators</strong> .................................................................. 7<br />

Table 2-1: Management Area Classes ................................................................................. 18<br />

Table 2-2: Amount of Protected <strong>and</strong> Park L<strong>and</strong> in <strong>Burrard</strong> <strong>Inlet</strong> Watershed<br />

(total area <strong>and</strong> % of l<strong>and</strong> in each management class) ........................................ 18<br />

Table 2-3: Proportion of L<strong>and</strong> in Management Classes for Each <strong>Burrard</strong><br />

<strong>Inlet</strong> Catchment ................................................................................................... 19<br />

Table 5-1: Common Sources <strong>and</strong> Contributors of GHGs ..................................................... 28<br />

Table 7-1: <strong>Burrard</strong> <strong>Inlet</strong> Beach Locations ............................................................................. 36<br />

List of Maps<br />

Map 1: Basins <strong>and</strong> Catchments of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Burrard</strong> <strong>Inlet</strong> Watershed ....................................... 4<br />

Map 2: Ortho-Image of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Burrard</strong> <strong>Inlet</strong> Watershed ......................................................... 5<br />

Map 3: Developable vs. Undeveloped Areas for <strong>the</strong> <strong>Burrard</strong> <strong>Inlet</strong> Catchments .............. 13<br />

Map 4: Location of Management Area Classes <strong>and</strong> RCAs in <strong>the</strong> <strong>Burrard</strong> <strong>Inlet</strong>............... 17<br />

Page | ii

<strong>Burrard</strong> <strong>Inlet</strong> <strong>Environmental</strong> <strong>Indicators</strong> <strong>Report</strong> February 2008<br />

List of Charts<br />

Chart 1-1: Current L<strong>and</strong> Cover across <strong>the</strong> Entire <strong>Burrard</strong> <strong>Inlet</strong> Watershed ..........................14<br />

Chart 1-2: Current L<strong>and</strong> Cover in Developable Areas of <strong>Burrard</strong> <strong>Inlet</strong>..................................14<br />

Chart 3-1: Waterbird Abundance in <strong>Burrard</strong> <strong>Inlet</strong> Since 1975...............................................21<br />

Chart 4-1: Smog Forming Pollutants in <strong>the</strong> Canadian Portion of <strong>the</strong> Lower Fraser<br />

Valley, 2005 .........................................................................................................25<br />

Chart 4-2: Total Smog Forming Pollutants (SFPs) in <strong>the</strong> Lower Fraser Valley<br />

(Canadian <strong>and</strong> United States Sources) ...............................................................25<br />

Chart 5-1: Total Annual Emissions of GHGs Within <strong>the</strong> <strong>Burrard</strong> <strong>Inlet</strong> Airshed<br />

(marine <strong>and</strong> l<strong>and</strong> sources, including vehicles) .....................................................29<br />

Chart 6-1: Copper Concentrations in <strong>Burrard</strong> <strong>Inlet</strong> Sediment (1985 to 2005).......................32<br />

Chart 6-2: PCB Concentration in <strong>Burrard</strong> <strong>Inlet</strong> Sediment (1985 to 2004) .............................33<br />

Chart 7-1: Number of Days <strong>Burrard</strong> <strong>Inlet</strong> Beaches were Closed for Swimming<br />

(2002 to 2006)......................................................................................................37<br />

Chart 7-2: Fecal Coliform Data for Deep Cove (2002 to 2006).............................................37<br />

Chart 7-3: Fecal Coliform Data for Old Orchard Park (2002 to 2006)...................................38<br />

Chart 7-4: Fecal Coliform Data for Sunset Beach (2002 to 2006) ........................................38<br />

List of Figures<br />

Figure 1: Examples of Contaminant Pathways in <strong>the</strong> <strong>Burrard</strong> <strong>Inlet</strong> <strong>and</strong> Strait of<br />

Georgia Ecosystems............................................................................................10<br />

Figure 5-1: Past <strong>and</strong> Future CO2 Levels in <strong>the</strong> Atmosphere ..................................................27<br />

Page | iii

<strong>Burrard</strong> <strong>Inlet</strong> <strong>Environmental</strong> <strong>Indicators</strong> <strong>Report</strong> February 2008<br />

Executive Summary<br />

The <strong>Burrard</strong> <strong>Inlet</strong> <strong>Environmental</strong> Action Program (<strong>BIEAP</strong>) is an inter-governmental partnership<br />

that coordinates environmental management of <strong>Burrard</strong> <strong>Inlet</strong>. In 2002, <strong>BIEAP</strong> prepared a<br />

Consolidated <strong>Environmental</strong> Management Plan (CEMP) to facilitate continued sustainability of<br />

<strong>the</strong> <strong>Inlet</strong>. Effectiveness of <strong>the</strong> CEMP can be assessed by following trends in indicators over<br />

time. These indicators will suggest whe<strong>the</strong>r current environmental management practices are<br />

successful in protecting <strong>Burrard</strong> <strong>Inlet</strong> or whe<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong>y should be refined.<br />

This consultation document was prepared to provide current information about certain<br />

environmental indicators <strong>and</strong> to help guide planning for future development in <strong>the</strong> <strong>Burrard</strong> <strong>Inlet</strong><br />

watershed. The report also describes ways in which <strong>the</strong> environment is being or can be<br />

protected by regulatory agencies, o<strong>the</strong>r decision-makers <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> public.<br />

Seven environmental indicators have been selected from a list of potential c<strong>and</strong>idates<br />

suggested by <strong>the</strong> many monitoring programs conducted over <strong>the</strong> past two decades. These<br />

were chosen because <strong>the</strong>ir existing data sets <strong>and</strong> on-going monitoring programs are<br />

sufficiently robust to reliably reflect <strong>the</strong> effects of human activities on <strong>Burrard</strong> <strong>Inlet</strong> air <strong>and</strong><br />

water quality 1 , <strong>and</strong> to demonstrate <strong>the</strong> consequences of l<strong>and</strong> development on ecosystem<br />

health. The selected indicators are tree canopy cover, parks <strong>and</strong> protected areas, waterbird<br />

abundance, air quality, greenhouse gas emissions, water <strong>and</strong> sediment quality (albeit only as<br />

reflected in copper <strong>and</strong> PCB levels), <strong>and</strong> recreational use <strong>and</strong> fecal coliform bacteria. For each<br />

indicator, four key questions are discussed in this document:<br />

• What actions can governments, agencies, industries <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> public take to maintain or<br />

improve <strong>the</strong> condition of this indicator? Why look at this indicator?<br />

• How are data ga<strong>the</strong>red <strong>and</strong> benchmarks established to evaluate <strong>the</strong> indicator?<br />

• What are <strong>the</strong> results <strong>and</strong> trends?<br />

• What actions can governments, agencies, industries <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> public take to maintain or<br />

improve <strong>the</strong> condition of this indicator?<br />

Table 1 provides a summary of <strong>the</strong> key findings <strong>and</strong> trends. Collectively, <strong>the</strong> indicators<br />

describe an ecosystem in fairly good condition, with improved sediment <strong>and</strong> air quality.<br />

However, <strong>the</strong>re continue to be challenges associated with human activities:<br />

• Tree canopy cover needed to provide a wide range of economic <strong>and</strong> ecosystem<br />

benefits is under continuous pressure from development<br />

• The occasional accidental release of contaminants <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> ongoing release of<br />

contaminants from storm water are still of concern<br />

• Contaminant concentrations in killer whales <strong>and</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r animals remain a serious issue<br />

in <strong>the</strong> Strait of Georgia because of persistence of some old compounds <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

emergence of new compounds <strong>and</strong> sources<br />

• Greenhouse gas emissions continue to increase with a growing population.<br />

The indicator data used in this report provide a baseline for comparison over time. They will<br />

help show whe<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong> environmental management practices described in <strong>the</strong> CEMP are<br />

fulfilling <strong>BIEAP</strong>’s m<strong>and</strong>ate <strong>and</strong> goals to protect <strong>the</strong> ecological functioning of <strong>Burrard</strong> <strong>Inlet</strong> while<br />

encouraging sustainable development, or whe<strong>the</strong>r adjustments to <strong>the</strong> Plan are needed.<br />

1<br />

However, <strong>the</strong>ir scope of coverage of environmental issues is at present not sufficient for a “State of <strong>the</strong><br />

Environment” report.<br />

Page | 1

<strong>Burrard</strong> <strong>Inlet</strong> <strong>Environmental</strong> <strong>Indicators</strong> <strong>Report</strong> February 2008<br />

<strong>BIEAP</strong> remains committed to translating information into action. As our underst<strong>and</strong>ing of <strong>the</strong><br />

connections between a healthy environment, society <strong>and</strong> economy deepens, we learn about<br />

<strong>the</strong> many actions that individuals, communities, businesses <strong>and</strong> corporations can take to<br />

maintain <strong>the</strong> health of <strong>Burrard</strong> <strong>Inlet</strong>.<br />

Table 1: Key Findings <strong>and</strong> Trends for <strong>Burrard</strong> <strong>Inlet</strong> <strong>Environmental</strong> <strong>Indicators</strong><br />

Indicator Current Status<br />

1. Tree Canopy<br />

Cover<br />

2. Parks <strong>and</strong><br />

Protected<br />

Areas<br />

3. Waterbird<br />

Abundance<br />

The urban tree canopy provides economically valuable environmental services such as<br />

improving air quality, purifying water <strong>and</strong> helping manage stormwater. It is assessed for<br />

developable <strong>and</strong> undeveloped areas of <strong>the</strong> watershed 2 based on 2002 satellite imagery. Tree<br />

canopy cover is 42% in <strong>the</strong> developable areas (ranging from 26% in <strong>the</strong> English Bay <strong>and</strong> Inner<br />

Harbour catchments to 84% in <strong>the</strong> Indian Arm catchment) <strong>and</strong> 96% in <strong>the</strong> higher elevation<br />

undeveloped areas. The 42% value for tree cover in <strong>the</strong> developable area is high compared to<br />

many cities in Canada <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> United States (25% to 40%), indicating that communities in <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>Inlet</strong> currently do a better than average job at protecting <strong>the</strong>ir urban forests. However, <strong>the</strong> 26%<br />

cover in some areas indicates <strong>the</strong> need to continue to protect urban forests through planning.<br />

In developable areas 2 , 59% of <strong>the</strong> l<strong>and</strong> is urban <strong>and</strong> suburban <strong>and</strong> 41% has some form<br />

of protection (wildlife reserve, regional or municipal park, green belt, golf course).<br />

Considering <strong>the</strong> entire watershed, 19% is urban <strong>and</strong> suburban l<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> 81% has some<br />

type of protection. These percentages are unlikely to change over time, as <strong>the</strong> l<strong>and</strong> uses<br />

are designated, but habitat quality may decrease recreational uses increases.<br />

Populations of four species of resident waterbirds (Double-crested Cormorant, Pelagic<br />

Cormorant, Black Oystercatcher) have been stable or increased since <strong>the</strong> mid 1990s.<br />

Glaucous-winged Gull populations have declined since 1975. Gulls are very sensitive to<br />

predation by <strong>the</strong> Bald Eagle, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir decreased abundance may reflect movement out<br />

of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Inlet</strong> as <strong>the</strong>y adapt to <strong>the</strong> increasing danger posed by eagles. Results for waterbird<br />

populations indicate stable <strong>and</strong> favourable environmental conditions in <strong>the</strong> <strong>Inlet</strong> to date.<br />

4. Air Quality Air quality in <strong>the</strong> <strong>Burrard</strong> <strong>Inlet</strong> airshed is currently acceptable most of <strong>the</strong> time, <strong>and</strong> has<br />

improved notably over <strong>the</strong> past 20 years. Levels of “Criteria Air Contaminants” generally<br />

are below Metro Vancouver management targets. Carbon monoxide, nitrogen dioxide<br />

<strong>and</strong> sulphur dioxide levels have declined since <strong>the</strong> 1980s. Particulate matter (PM10) <strong>and</strong><br />

ozone levels have been more stable. There are not enough data yet for PM2.5 to establish<br />

a time trend. Emissions of smog-forming pollutants have declined steadily since 1985.<br />

5. Greenhouse<br />

Gas<br />

Emissions<br />

6. Water <strong>and</strong><br />

Sediment<br />

Quality<br />

(copper <strong>and</strong><br />

PCB levels)<br />

7. Recreational<br />

Use <strong>and</strong><br />

Fecal<br />

Coliform<br />

Bacteria<br />

Greenhouse gas emissions (carbon dioxide, methane, nitrous oxide) have increased steadily<br />

since 1990 <strong>and</strong> are projected to increase along with population growth. The rate of increase has<br />

slowed since 1990 (from 19% increase between 1990 <strong>and</strong> 1995 to 7% increase between 2000<br />

<strong>and</strong> 2005). Emissions are projected to increase by 4% per five-year period to 2025.<br />

Copper levels in water are variable; although 20% of samples collected since 1985<br />

exceeded <strong>the</strong> provincial water quality guideline for copper, no trend over time is<br />

apparent. Copper levels in sediment have declined since 1985, although two locations<br />

(Outer Harbour North, Inner Harbour) still exceeded <strong>Burrard</strong> <strong>Inlet</strong> sediment quality<br />

guidelines in 2005. In <strong>the</strong> 1980s, PCB levels in sediment were well above <strong>Burrard</strong> <strong>Inlet</strong><br />

guidelines at most sites; however, levels have decreased markedly at most sites. Four of<br />

six samples collected in 2004 were below objectives but two sites (False Creek <strong>and</strong> Inner<br />

Harbour) remained above objectives. The trend of improved levels of copper <strong>and</strong> PCB in<br />

sediment over time is related to reduced discharges of <strong>the</strong>se contaminants.<br />

Water quality at 15 of <strong>the</strong> 19 <strong>Burrard</strong> <strong>Inlet</strong> beaches is excellent for swimming, with no closures<br />

for elevated coliform levels over <strong>the</strong> past five years. Four beaches (Deep Cove <strong>and</strong> Cates Park<br />

in North Vancouver, Barnet Marine Park <strong>and</strong> Old Orchard Park in Port Moody) had periodic<br />

closures in 2002, 2005 <strong>and</strong> 2006, in part related to <strong>the</strong> lower amount of tidal flushing in <strong>the</strong>se<br />

areas. Fecal coliforms are present at o<strong>the</strong>r beaches but not at, levels high enough to trigger<br />

beach closures. Shellfish harvesting has been prohibited in <strong>Burrard</strong> <strong>Inlet</strong> since <strong>the</strong> 1970’s.<br />

There have been no closures for secondary contact recreation (boating, kayaking, windsurfing).<br />

2<br />

The boundary for developable vs. undeveloped l<strong>and</strong> is set at 320 m elevation to <strong>the</strong> west of Lynn Creek (in<br />

North Vancouver) <strong>and</strong> 200 m to <strong>the</strong> east.<br />

Page | 2

<strong>Burrard</strong> <strong>Inlet</strong> <strong>Environmental</strong> <strong>Indicators</strong> <strong>Report</strong> February 2008<br />

PART 1 – Setting <strong>the</strong> Context<br />

Overview of <strong>BIEAP</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> Region<br />

The <strong>Burrard</strong> <strong>Inlet</strong> <strong>Environmental</strong> Action<br />

Program (<strong>BIEAP</strong>) was established in<br />

1991 to provide a management<br />

framework to protect <strong>and</strong> improve <strong>the</strong><br />

environmental quality of <strong>Burrard</strong> <strong>Inlet</strong>’s<br />

ecosystem. <strong>BIEAP</strong> brings toge<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong><br />

agencies responsible for setting <strong>and</strong><br />

enforcing environmental legislation <strong>and</strong><br />

policy with those responsible for l<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong><br />

water management to coordinate<br />

planning <strong>and</strong> operational decision-making<br />

False Creek <strong>and</strong> surrounding area<br />

to ensure a sustainable future for <strong>Burrard</strong> <strong>Inlet</strong>. <strong>BIEAP</strong> provides environmental assessments of<br />

development projects within <strong>Burrard</strong> <strong>Inlet</strong>, with partners using a consensus-based approach to<br />

finding ‘made in <strong>the</strong> <strong>Inlet</strong>’ environmental management solutions. Partners <strong>and</strong> communities<br />

bordering <strong>the</strong> <strong>Inlet</strong> are listed in Table 2.<br />

Table 2: <strong>BIEAP</strong> Partners <strong>and</strong> Communities Bordering <strong>Burrard</strong> <strong>Inlet</strong><br />

The <strong>BIEAP</strong> Partners Communities Bordering <strong>Burrard</strong> <strong>Inlet</strong><br />

BC Ministry of Environment<br />

Environment Canada<br />

Fisheries <strong>and</strong> Oceans Canada<br />

Transport Canada<br />

Metro Vancouver<br />

Vancouver Port Authority<br />

Village of Anmore<br />

Village of Belcarra<br />

City of Burnaby<br />

City of North Vancouver<br />

District of North Vancouver<br />

City of Port Moody<br />

City of Vancouver<br />

District of West Vancouver<br />

Geographically, <strong>BIEAP</strong> jurisdiction includes <strong>the</strong> marine foreshore <strong>and</strong> tidal waters east of a line<br />

between Point Atkinson <strong>and</strong> Point Grey, including False Creek, Port Moody Arm <strong>and</strong> Indian<br />

Arm. It also includes upl<strong>and</strong> areas that drain into <strong>the</strong> <strong>Inlet</strong> because activities on <strong>the</strong> l<strong>and</strong><br />

influence conditions in <strong>the</strong> water. All or portions of eight municipalities bordering <strong>the</strong> <strong>Inlet</strong> form<br />

<strong>the</strong> <strong>Burrard</strong> <strong>Inlet</strong> watershed. Map 1 shows <strong>the</strong> basins (water areas) <strong>and</strong> catchments (l<strong>and</strong><br />

areas) of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Burrard</strong> <strong>Inlet</strong> watershed:<br />

• six basins – Outer Harbour, Inner Harbour, Central Harbour, False Creek, Port Moody<br />

Arm <strong>and</strong> Indian Arm <strong>and</strong><br />

• four catchments – English Bay, Inner Harbour, Indian Arm <strong>and</strong> Port Moody Arm.<br />

<strong>Burrard</strong> <strong>Inlet</strong><br />

<strong>Burrard</strong> <strong>Inlet</strong> is in <strong>the</strong> traditional territories of many Coast Salish peoples, including <strong>the</strong> Tsleil-<br />

Waututh, Squamish <strong>and</strong> Musqueam First Nations. Over <strong>the</strong> last 150 years, <strong>the</strong> inlet has seen<br />

much change. With European settlement, it became <strong>the</strong> active port of a burgeoning west coast<br />

timber industry <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> industrial centre of <strong>the</strong> province. In recent years, <strong>the</strong> <strong>Inlet</strong> has become<br />

<strong>the</strong> centre of a highly urbanized city-region <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> Port of Vancouver now serves <strong>the</strong><br />

increasing needs of international trade.<br />

Page | 3

<strong>Burrard</strong> <strong>Inlet</strong> <strong>Environmental</strong> <strong>Indicators</strong> <strong>Report</strong> February 2008<br />

Map 1: Basins <strong>and</strong> Catchments of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Burrard</strong> <strong>Inlet</strong> Watershed<br />

Adapted from <strong>BIEAP</strong><br />

The mountains of <strong>the</strong> North Shore <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> waters of <strong>Burrard</strong> <strong>Inlet</strong> give Vancouver its<br />

reputation as one of <strong>the</strong> most scenic cities in <strong>the</strong> world. Over 650,000 people live in <strong>the</strong><br />

watershed <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong>y, along with visitors <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> remaining 1.4 million lower mainl<strong>and</strong> residents,<br />

enjoy <strong>the</strong> many recreational opportunities <strong>the</strong> <strong>Inlet</strong> provides. Characterized by a temperate<br />

marine climate, <strong>the</strong> <strong>Burrard</strong> <strong>Inlet</strong> ecosystem includes rugged mountain peaks, magnificent old<br />

growth forests <strong>and</strong> fjords rich with terrestrial <strong>and</strong> aquatic life. Its forested slopes provide habitat<br />

for deer, bears, cougars <strong>and</strong> many small animals <strong>and</strong> birds <strong>and</strong> its shorelines, intertidal areas,<br />

mudflats <strong>and</strong> salt marshes support many species of marine organisms. The Pacific Flyway<br />

transects <strong>the</strong> inlet, attracting tens of thous<strong>and</strong>s of migratory birds each year. An aerial view<br />

(Map 2) shows <strong>the</strong> variety of natural <strong>and</strong> developed l<strong>and</strong>scapes of <strong>the</strong> watershed.<br />

Page | 4

<strong>Burrard</strong> <strong>Inlet</strong> <strong>Environmental</strong> <strong>Indicators</strong> <strong>Report</strong> February 2008<br />

Map 2: Ortho-Image of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Burrard</strong> <strong>Inlet</strong> Watershed<br />

Source: Metro Vancouver<br />

Page | 5

<strong>Burrard</strong> <strong>Inlet</strong> <strong>Environmental</strong> <strong>Indicators</strong> <strong>Report</strong> February 2008<br />

Consolidated <strong>Environmental</strong> Management Plan<br />

<strong>Environmental</strong> management of such a rich area requires balancing many priorities of <strong>the</strong><br />

human population while ensuring clean air, water <strong>and</strong> habitat for both humans <strong>and</strong> wildlife. In<br />

addition to <strong>the</strong> effects of current <strong>and</strong> future l<strong>and</strong> use, legacies from historic activities have left<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir imprint. These include accumulations of contaminants such as heavy metals or organic<br />

compounds (e.g., petroleum products, poly-chlorinated biphenyls [PCBs]), loss of stream <strong>and</strong><br />

shoreline habitat, <strong>and</strong> closure of shellfish harvesting due to fecal coliform levels.<br />

<strong>BIEAP</strong>’s Consolidated <strong>Environmental</strong> Management Plan (CEMP) was approved in 2002 <strong>and</strong><br />

provides a framework for improving <strong>the</strong> environmental quality of <strong>Burrard</strong> <strong>Inlet</strong>. The four main<br />

goals of <strong>the</strong> CEMP are to:<br />

• Improve water quality in <strong>Burrard</strong> <strong>Inlet</strong><br />

• Minimize <strong>the</strong> effects of contaminated soils <strong>and</strong> sediments on human <strong>and</strong> ecological<br />

health<br />

• Maintain <strong>and</strong> enhance productive fish <strong>and</strong> wildlife habitat <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> natural biodiversity of<br />

<strong>Burrard</strong> <strong>Inlet</strong><br />

• Encourage human <strong>and</strong> economic development activities that enhance <strong>the</strong><br />

environmental quality of <strong>Burrard</strong> <strong>Inlet</strong><br />

The Plan consolidates all <strong>the</strong> environmental<br />

management systems employed by <strong>the</strong> <strong>BIEAP</strong><br />

partners to protect <strong>Burrard</strong> <strong>Inlet</strong>. The CEMP will<br />

help ensure that environmental values are<br />

integrated with economic <strong>and</strong> social considerations<br />

for <strong>the</strong> <strong>Inlet</strong>. It establishes a common basis for<br />

reviewing development proposals <strong>and</strong> recommends<br />

facilitation, research <strong>and</strong> information sharing to<br />

improve <strong>and</strong> enhance <strong>the</strong> <strong>Inlet</strong>’s ecosystem over<br />

time. A Plan Implementation Committee was<br />

established in 2003 to help implement <strong>the</strong> CEMP<br />

<strong>and</strong> monitor its performance.<br />

State of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Burrard</strong> <strong>Inlet</strong> Environment<br />

One of <strong>the</strong> key commitments of <strong>the</strong> CEMP is to<br />

prepare a State of Environment report for <strong>Burrard</strong><br />

<strong>Inlet</strong>. In 2004, <strong>BIEAP</strong> began researching potential<br />

indicators that could be used to describe <strong>the</strong> status <strong>and</strong> trends in <strong>the</strong> <strong>Inlet</strong> to policy makers,<br />

planners <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> general public. Many datasets <strong>and</strong> 19 distinct indicators were evaluated for<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir ability to ‘tell <strong>the</strong> story’ of <strong>Burrard</strong> <strong>Inlet</strong> accurately (reliable dataset, ability to provide<br />

science-based statements on <strong>the</strong> state of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Inlet</strong>) <strong>and</strong> help <strong>the</strong> public underst<strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

interconnected nature of <strong>the</strong> ecosystem. Although <strong>the</strong>re are a lot of data, <strong>the</strong>y did not always<br />

allow for conclusive, science-based statements to be made. <strong>BIEAP</strong> settled on seven key<br />

indicators that, taken toge<strong>the</strong>r, help describe <strong>the</strong> complex relationship between human actions<br />

<strong>and</strong> environmental conditions in <strong>Burrard</strong> <strong>Inlet</strong>. These indicators will be monitored over time to<br />

assess performance of <strong>the</strong> CEMP <strong>and</strong> contribute information to a State of Environment report.<br />

Page | 6

<strong>Burrard</strong> <strong>Inlet</strong> <strong>Environmental</strong> <strong>Indicators</strong> <strong>Report</strong> February 2008<br />

<strong>Indicators</strong> Used to Monitor <strong>the</strong> CEMP<br />

The CEMP uses a risk management approach; it has identified priority ecosystem risks <strong>and</strong><br />

issues <strong>and</strong> selected indicators to monitor <strong>the</strong> risks. Table 3 lists <strong>the</strong> indicators used, which fall<br />

into two types:<br />

• those that quantify ecosystem assets, such as <strong>the</strong> water’s ability to supply nutrients to<br />

fish <strong>and</strong> birds, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> tree canopy’s ability to purify air<br />

• those that assess <strong>the</strong> impacts of human activities on air <strong>and</strong> water.<br />

Table 3: <strong>Burrard</strong> <strong>Inlet</strong> <strong>Environmental</strong> <strong>Indicators</strong><br />

Indicator<br />

Type<br />

Quantifies<br />

ecosystem<br />

assets<br />

Describes<br />

impacts of<br />

human<br />

activities<br />

Indicator Relevance<br />

1. Tree Canopy Cover A measure of current levels of l<strong>and</strong> development;<br />

recognizes <strong>the</strong> importance of forested l<strong>and</strong> in purifying water<br />

<strong>and</strong> air, storing carbon <strong>and</strong> managing stormwater runoff<br />

2. Parks <strong>and</strong> Protected<br />

Areas<br />

A measure of <strong>the</strong> amount of l<strong>and</strong> protected for wildlife<br />

habitat <strong>and</strong> for recreational use<br />

3. Waterbird Abundance An indicator of general ecosystem condition, as bird<br />

abundance depends on amounts of available habitat <strong>and</strong><br />

food, <strong>and</strong> is affected by levels of contaminants in <strong>the</strong> area<br />

4. Air Quality Related to vehicle, vessel, residential <strong>and</strong> industrial<br />

emissions; has socio-economic implications (human health,<br />

smog) <strong>and</strong> environmental implications (acid rain)<br />

5. Greenhouse Gas<br />

Emissions<br />

6. Water <strong>and</strong> Sediment<br />

Quality (copper <strong>and</strong><br />

PCB levels)<br />

7. Recreational Use <strong>and</strong><br />

Fecal Coliform Bacteria<br />

Related to amounts of fossil fuels burned <strong>and</strong> to global<br />

climate change<br />

Related to discharges to water from point sources (permitted<br />

outfalls) <strong>and</strong> non-point sources (stormwater, road runoff,<br />

contaminated sites, air deposition) <strong>and</strong> affects <strong>the</strong> health of<br />

aquatic organisms<br />

Related to fecal contamination (human <strong>and</strong> animal waste) in<br />

<strong>the</strong> water; affects recreational uses such as swimming,<br />

boating <strong>and</strong> harvesting of shellfish<br />

Because <strong>the</strong> high elevation forested mountain terrain will not be developed, indicators of l<strong>and</strong><br />

use are evaluated in terms of <strong>the</strong> lower elevation l<strong>and</strong> where development has taken place or<br />

will occur. The highest elevation where development can be planned is 320 m in West<br />

Vancouver <strong>and</strong> in North Vancouver west of Lynn Creek <strong>and</strong> 200 m in areas to <strong>the</strong> east of Lynn<br />

Creek. Results are also discussed for <strong>the</strong> higher elevation areas because <strong>the</strong>se areas<br />

contribute significantly to watershed functioning.<br />

Page | 7

<strong>Burrard</strong> <strong>Inlet</strong> <strong>Environmental</strong> <strong>Indicators</strong> <strong>Report</strong> February 2008<br />

Part 2 – Links Between Human Activities <strong>and</strong> <strong>Burrard</strong> <strong>Inlet</strong> Status<br />

Before discussing <strong>the</strong> indicators in detail, it is useful to look at <strong>the</strong> types of human activities<br />

that affect <strong>the</strong> state of <strong>Burrard</strong> <strong>Inlet</strong>, in terms of availability of wildlife habitat, introduced<br />

invasive species, <strong>and</strong> sources of contaminants <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir effects on birds, fish <strong>and</strong> mammals in<br />

<strong>the</strong> <strong>Inlet</strong>. This information adds context about historic <strong>and</strong> current activities <strong>and</strong> illustrates <strong>the</strong><br />

interconnectedness of <strong>the</strong> ecosystem.<br />

Habitat <strong>and</strong> shoreline change over time<br />

Stanley Park Seawalk<br />

The 190 km of shoreline <strong>and</strong> 11,300 hectares of water<br />

<strong>and</strong> seabed of <strong>Burrard</strong> <strong>Inlet</strong> are biologically diverse<br />

ecosystems that provide habitat for many species of<br />

fish <strong>and</strong> shellfish. Changes to <strong>the</strong>se habitats can have<br />

significant consequences, <strong>and</strong> can occur as a result of<br />

natural processes as well as human activities. The<br />

<strong>Burrard</strong> <strong>Environmental</strong> Review Committee (BERC), a<br />

<strong>BIEAP</strong> subcommittee of agencies with project<br />

environmental review m<strong>and</strong>ates, began reviewing<br />

project proposals in <strong>Burrard</strong> <strong>Inlet</strong> in 1991. BERC<br />

objectives are to ensure that projects are designed <strong>and</strong><br />

located to minimize or avoid significant habitat impacts<br />

<strong>and</strong> to promote habitat development.<br />

Significant changes in <strong>Burrard</strong> <strong>Inlet</strong> have taken place<br />

since <strong>the</strong> start of European settlement, <strong>and</strong> have resulted<br />

in substantial declines in some habitat types (e.g., salt<br />

marsh <strong>and</strong> tidal flats). However, <strong>the</strong> BERC project review<br />

process helps ensure that fur<strong>the</strong>r human-induced habitat<br />

changes over time are neutral or positive.<br />

Invasive marine species<br />

Invasive species have massive potential for<br />

ecological <strong>and</strong> economic impacts on existing<br />

species <strong>and</strong> habitat. Most invasive marine<br />

species found in <strong>Burrard</strong> <strong>Inlet</strong> were accidentally<br />

introduced through ship ballast water, pleasure<br />

boat traffic <strong>and</strong> ocean currents (e.g., Manila <strong>and</strong><br />

varnish clams), although some (Japanese oyster)<br />

were intentionally imported to increase shellfish<br />

production.<br />

Introduced species pose a risk to <strong>the</strong> environment<br />

by taking over habitat used by native species.<br />

Two categories of invasive marine species can be<br />

considered: those that were introduced decades<br />

ago <strong>and</strong> are now well established (making it<br />

difficult to eliminate <strong>the</strong>m) <strong>and</strong> those that have<br />

been recently introduced (where a program to<br />

eliminate <strong>the</strong>m may still be successful).<br />

Currently <strong>the</strong> risks from invasive marine plants<br />

are considered relatively low; however, <strong>the</strong><br />

status of <strong>the</strong>se organisms should be reviewed<br />

periodically. The Vancouver Port Authority is<br />

reducing <strong>the</strong> risk of ongoing introduction of<br />

invasive marine species by requiring exchange<br />

of ship ballast water at mid-ocean to prevent<br />

introduction of Asian Pacific species to <strong>the</strong><br />

west coast.<br />

Recent introductions <strong>and</strong> threats<br />

English cord grass (Spartina anglica), identified<br />

at Roberts Bank <strong>and</strong> Boundary Bay in Delta in<br />

2003, but not yet in <strong>Burrard</strong> <strong>Inlet</strong>; this plant has<br />

an aggressive growth pattern <strong>and</strong> high potential<br />

for damage.<br />

Salt marsh cord grass (Spartina patens), found at<br />

<strong>the</strong> western boundary of Maplewood<br />

Conservation Area; has spread to Port Moody<br />

Arm <strong>and</strong> possibly to o<strong>the</strong>r areas.<br />

Page | 8

<strong>Burrard</strong> <strong>Inlet</strong> <strong>Environmental</strong> <strong>Indicators</strong> <strong>Report</strong> February 2008<br />

Contaminants<br />

There are many sources of contaminants in <strong>Burrard</strong> <strong>Inlet</strong>: combined sewer overflows,<br />

wastewater treatment plant discharges <strong>and</strong> non-point sources such as stormwater runoff <strong>and</strong><br />

atmospheric deposition, seepage from contaminated sites <strong>and</strong> spills or accidental releases of<br />

oils <strong>and</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r compounds. Some compounds (e.g., PCBs, PBDEs) persist in <strong>the</strong> sediment, are<br />

taken up by worms <strong>and</strong> shellfish <strong>and</strong>, because <strong>the</strong>y tend to be stored in fatty tissue, become<br />

highly concentrated in predators such as whales <strong>and</strong> fish-eating birds. Contaminants can also<br />

be passed on to humans, where <strong>the</strong>y can lead to disease. Figure 1 describes some pathways<br />

of contaminants in <strong>Burrard</strong> <strong>Inlet</strong>, from source to effects on organisms in <strong>the</strong> <strong>Burrard</strong> <strong>Inlet</strong><br />

ecosystem <strong>and</strong> beyond.<br />

O<strong>the</strong>r Potential <strong>Indicators</strong> for a <strong>Burrard</strong> <strong>Inlet</strong> State of Environment <strong>Report</strong><br />

The Plan Implementation Committee is considering additional indicators to monitor <strong>the</strong> state of<br />

environment in <strong>Burrard</strong> <strong>Inlet</strong>. As additional information becomes available, some of <strong>the</strong><br />

following topics may provide useful monitoring tools:<br />

• species at risk<br />

• mussel health<br />

• total <strong>and</strong> effective impervious (impermeable) area<br />

• health of benthic invertebrate communities in streams<br />

• marine mammal abundance or levels of contaminants in tissue<br />

• Industrial permits (numbers, discharge loadings, characteristics)<br />

• stormwater monitoring data for streams<br />

• water quality assessment using <strong>the</strong> Canadian Water Quality Index for a full suite of<br />

monitored parameters<br />

• trends in air quality health index, CCME sediment quality index <strong>and</strong> new soil quality index<br />

Including <strong>the</strong>se indicators would give a wider breadth to our underst<strong>and</strong>ing of ecosystem<br />

health in <strong>Burrard</strong> <strong>Inlet</strong>. Additional trends would enable decision makers to assess with<br />

increased certainty <strong>the</strong> ecosystem risks of development activities <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> benefits of toxin<br />

reduction efforts. Over time, <strong>the</strong>se indicators would offer a robust picture of how human<br />

populations are having an impact on <strong>the</strong> local ecosystem.<br />

Page | 9

<strong>Burrard</strong> <strong>Inlet</strong> <strong>Environmental</strong> <strong>Indicators</strong> <strong>Report</strong> February 2008<br />

This page left blank intentionally

<strong>Burrard</strong> <strong>Inlet</strong> <strong>Environmental</strong> <strong>Indicators</strong> <strong>Report</strong> February 2008<br />

Figure 1: Examples of Contaminant Pathways in <strong>the</strong> <strong>Burrard</strong> <strong>Inlet</strong> <strong>and</strong> Strait of Georgia Ecosystems<br />

Contaminated sites<br />

The provincial Ministry of Environment maintains a database with reports<br />

on sites that are or may be contaminated. A contaminated site in B.C. is<br />

defined as an area of l<strong>and</strong> in which <strong>the</strong> soil or underlying groundwater or<br />

sediment contains a hazardous substance in an amount or concentration<br />

that exceeds provincial environmental quality st<strong>and</strong>ards. The st<strong>and</strong>ards<br />

vary according to l<strong>and</strong> use <strong>and</strong> closeness to a waterway.<br />

Sites may be contaminated because of previous commercial or industrial<br />

activity that deposited or spilled contaminants into surrounding l<strong>and</strong>.<br />

Examples include gas stations, wood treatment operations, ab<strong>and</strong>oned<br />

underground oil tanks, rail <strong>and</strong> port facilities <strong>and</strong> dry-cleaning shops.<br />

Sites may contain metals (e.g., lead, arsenic, cadmium, mercury),<br />

petroleum hydrocarbons (benzene, toluene <strong>and</strong> polycyclic aromatic<br />

hydrocarbons from gasoline <strong>and</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r sources) <strong>and</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r organic<br />

compounds (polychlorinated biphenyls from electrical equipment,<br />

chlorophenols in wood preservatives).<br />

Professional environmental site assessors conduct a formal process for<br />

investigating <strong>and</strong> cleaning up a contaminated site to an appropriate<br />

st<strong>and</strong>ard. Although contaminated sites may not be a visible hazard, it is<br />

important to remediate <strong>the</strong>m to prevent contamination from leaching into<br />

<strong>the</strong> groundwater <strong>and</strong> fur<strong>the</strong>r afield.<br />

Contaminants from Combined Sewer Overflows, stormwater,<br />

wastewater treatment plants, <strong>and</strong> industrial discharges<br />

Please see Indicator 6.<br />

Spills in <strong>Burrard</strong> <strong>Inlet</strong><br />

Sources of coliforms in waterways<br />

Please see Indicator 7.<br />

Contaminants sometimes enter <strong>Burrard</strong> <strong>Inlet</strong> through accidental spills. Most spills are shorebased<br />

<strong>and</strong> small, although spills from vessels <strong>and</strong> unidentified sources also occur. The larger<br />

spills (e.g., release of canola oil during loading of a vessel in 1999; release of crude oil from a<br />

rupture of <strong>the</strong> Kinder Morgan oil pipeline in 2007) occur infrequently <strong>and</strong> are relatively easy to<br />

trace. Small spills can be difficult to trace <strong>and</strong> may not be recorded or cleaned up, but are a<br />

chronic source of contaminants to <strong>the</strong> inlet.<br />

Hydrocarbons (bunker, gasoline <strong>and</strong> diesel fuel, canola oil) are <strong>the</strong> most commonly reported<br />

compounds spilled. The resulting oil sheen is highly visible <strong>and</strong> can have immediate negative<br />

effects on wildlife <strong>and</strong> plant life (e.g., oiled birds, which may die from exposure), as well as longer<br />

term effects of <strong>the</strong> contaminants. O<strong>the</strong>r types of spills can be more difficult to detect.<br />

There is a coordinated oil spill response plan for <strong>Burrard</strong> <strong>Inlet</strong>. The Port Authority <strong>and</strong><br />

Environment Canada organize an emergency response when a spill is reported. For oil spills,<br />

<strong>Burrard</strong> Clean Operations deploys equipment to contain <strong>and</strong> remove <strong>the</strong> oil. Given <strong>the</strong> amount of<br />

industry, rail <strong>and</strong> port activity in <strong>the</strong> inner harbour, this is <strong>the</strong> area with <strong>the</strong> highest number of<br />

spills reported. Many companies have minimized spill risk by developing management plans,<br />

building containment facilities <strong>and</strong> training staff in spill response.<br />

<strong>Burrard</strong> <strong>Inlet</strong> Ecosystem<br />

<strong>Indicators</strong><br />

1. Tree Canopy Cover<br />

2. Parks <strong>and</strong> Protected Areas<br />

3. Waterbird Abundance<br />

4. Air Quality<br />

5. Greenhouse Gas Emissions<br />

6. Water <strong>and</strong> Sediment Quality<br />

7. Recreational Use <strong>and</strong> Fecal<br />

Coliform Bacteria<br />

Contaminants in birds<br />

There are many causes of fluctuations or declines in bird numbers, such as<br />

loss of overwintering or breeding habitat, increases in predation, or changes in<br />

food supply. However, many species of birds take up contaminants along with<br />

food in <strong>the</strong>ir diet, which can have an impact on bird health <strong>and</strong> populations.<br />

Levels of organic contaminants have been studied in several waterbird<br />

species in British Columbia over <strong>the</strong> past 25 years, although not specifically in<br />

<strong>Burrard</strong> <strong>Inlet</strong>. These studies, many by Environment Canada scientists, have<br />

looked at relationships between industrial discharges, contaminant levels in<br />

sediment <strong>and</strong> prey organisms (fish, shellfish), <strong>and</strong> health of bird populations<br />

(Elliot et al. 2001, 2001a, 2005, 2007; Harris et al. 2003, 2005, 2007).<br />

Levels of dioxins, furans, PCBs <strong>and</strong> organochlorine pesticides have declined<br />

in eggs of herons, cormorants <strong>and</strong> osprey over <strong>the</strong> study period, while levels<br />

of PBDEs have increased. <strong>Report</strong>ed biological effects include deformities in<br />

chicks, thin egg shells <strong>and</strong> altered physiology <strong>and</strong> biochemistry.<br />

Levels of butyltin (anti-fouling agent in marine paints) <strong>and</strong> some o<strong>the</strong>r metals<br />

were significantly higher in livers of surf scoters that overwinter in Vancouver<br />

harbour than in scoters from an undisturbed area on Vancouver Isl<strong>and</strong>, <strong>and</strong><br />

levels increased over <strong>the</strong> winter (Harris et al., 2007). The study also measured<br />

a decrease in body condition with increase in butyltin levels, suggesting a link<br />

between bird health <strong>and</strong> extent of industrialization in <strong>the</strong>ir winter habitat as<br />

<strong>the</strong>y prepare to migrate to breeding habitat.<br />

These trends reflect improved environmental management (e.g., changes in<br />

pulp mill bleaching processes, restrictions on use of PCBs, tributyl tin, wood<br />

preservatives, anti-sapstain compounds <strong>and</strong> several pesticides) for legacy<br />

contaminants <strong>and</strong> introduction of new contaminants of concern (e.g., PBDEs).<br />

However, results also show <strong>the</strong> persistence of many legacy compounds in <strong>the</strong><br />

environment, decades after <strong>the</strong>ir use has been eliminated, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir longrange<br />

transport <strong>and</strong> deposition from <strong>the</strong> air.<br />

Flame retardants (PBDEs) in marine mammals<br />

Polybrominated diphenyl e<strong>the</strong>rs (PBDEs) have been used as fire-retardants<br />

since <strong>the</strong> 1970s. In 2006 <strong>the</strong> Ministers of Environment <strong>and</strong> Health recommended<br />

that PBDEs be added to <strong>the</strong> List of Toxic Substances in <strong>the</strong> Canadian<br />

<strong>Environmental</strong> Protection Act 1999. It was concluded that PBDEs are entering<br />

<strong>the</strong> environment in a quantity or concentration or under conditions that have or<br />

may have an immediate or long-term harmful effect on <strong>the</strong> environment or its<br />

biological diversity.<br />

PBDEs are present in many consumer products, including electronics, plastics,<br />

upholstery, carpets <strong>and</strong> textiles. Although PBDEs are not produced in Canada,<br />

<strong>the</strong>y are imported in consumer products <strong>and</strong> for use in manufacturing. PBDEs<br />

are released to <strong>the</strong> environment when products are made or disposed of. Like<br />

polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), PBDEs degrade very slowly <strong>and</strong> are<br />

transported widely by winds <strong>and</strong> currents, even into pristine areas. They settle in<br />

<strong>the</strong> sediment <strong>and</strong> enter <strong>the</strong> food chain through benthic organisms, making <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

way up to marine mammals through fish such as salmon <strong>and</strong> herring. PBDEs are<br />

toxic to humans <strong>and</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r animals, are easily stored in fatty tissue <strong>and</strong><br />

biomagnify <strong>and</strong> bioaccumulate in <strong>the</strong> food chain. Elevated levels of PBDEs have<br />

been measured in resident killer whales in <strong>the</strong> Strait of Georgia (Ross 2006).<br />

Page | 10

<strong>Burrard</strong> <strong>Inlet</strong> <strong>Environmental</strong> <strong>Indicators</strong> <strong>Report</strong> February 2008<br />

Part 3 – The <strong>Indicators</strong><br />

1. Tree Canopy Cover<br />

2. Parks <strong>and</strong> Protected Areas<br />

3. Waterbird Abundance<br />

4. Air Quality<br />

5. Greenhouse Gas Emissions<br />

6. Water <strong>and</strong> Sediment Quality<br />

7. Recreational Use <strong>and</strong> Fecal Coliform Bacteria<br />

Page | 11

<strong>Burrard</strong> <strong>Inlet</strong> <strong>Environmental</strong> <strong>Indicators</strong> <strong>Report</strong> February 2008<br />

This page left blank intentionally

<strong>Burrard</strong> <strong>Inlet</strong> <strong>Environmental</strong> <strong>Indicators</strong> <strong>Report</strong> February 2008<br />

1. Tree Canopy Cover<br />

Why look at tree canopy cover?<br />

Natural vegetation, measured as tree canopy, provides<br />

many ecosystem <strong>and</strong> economic benefits. Tree canopy is<br />

particularly valuable in an urban environment, where<br />

development tends to replace natural vegetation with paved<br />

surfaces. L<strong>and</strong> use in <strong>the</strong> <strong>Burrard</strong> <strong>Inlet</strong> watershed includes<br />

urban <strong>and</strong> residential areas at lower elevations <strong>and</strong> forested<br />

mountain terrain at higher elevations.<br />

Measuring tree canopy over time in <strong>the</strong> developable area<br />

will track how well <strong>the</strong> region balances population growth<br />

<strong>and</strong> development with ecosystem health. A decrease in tree<br />

cover could be a trigger for policy makers to increase<br />

Benefits of trees<br />

Treed areas <strong>and</strong> a healthy tree canopy<br />

provide many benefits to urban, residential<br />

<strong>and</strong> undeveloped areas, such as:<br />

• removing air pollutants<br />

• providing shade<br />

• providing natural rainwater<br />

management<br />

• taking up carbon dioxide<br />

• evapotranspiration of up to 1/3 of<br />

rainfall<br />

• recharging groundwater <strong>and</strong> increasing<br />

summer stream flows<br />

• providing wildlife habitat <strong>and</strong><br />

maintaining biodiversity<br />

When tree cover is reduced during<br />

development, <strong>the</strong>se functions can be<br />

reduced. Communities replace lost natural<br />

services with infrastructure, such as<br />

stormwater conveyance <strong>and</strong> treatment<br />

systems, <strong>and</strong> pay for long-term health <strong>and</strong><br />

economic issues related to air quality <strong>and</strong><br />

o<strong>the</strong>r contaminants.<br />

Lions Gate Bridge <strong>and</strong> North Shore<br />

Mountains<br />

protection of tree canopy in <strong>the</strong> approval processes for l<strong>and</strong> development.<br />

Current status: Tree canopy cover is currently 42% of <strong>the</strong> entire developable watershed, <strong>and</strong> ranges<br />

from approximately 26% in English Bay <strong>and</strong> Inner Harbour catchments to 84% in Indian Arm catchment.<br />

Using tree canopy an indicator<br />

The amount of tree canopy provides an indicator of<br />

how l<strong>and</strong> is used today <strong>and</strong> can be used to monitor<br />

changes in <strong>the</strong> future. To describe <strong>the</strong> indicator, <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>Burrard</strong> <strong>Inlet</strong> watershed has been divided into two<br />

categories (undeveloped <strong>and</strong> developable l<strong>and</strong>) <strong>and</strong><br />

four catchments (English Bay, Indian Arm, Inner<br />

Harbour <strong>and</strong> Port Moody Arm) as shown in Map 3.<br />

Undeveloped l<strong>and</strong> is defined as higher elevation areas<br />

that will remain mostly forested. Developable l<strong>and</strong><br />

includes lower elevation l<strong>and</strong> that contains or has <strong>the</strong><br />

potential to become urban <strong>and</strong> residential areas. 3<br />

The <strong>Burrard</strong> <strong>Inlet</strong> watershed has a total area of<br />

98,235 ha, with 76% of l<strong>and</strong> in <strong>the</strong> undeveloped area<br />

<strong>and</strong> 24% in <strong>the</strong> developable area. The undeveloped<br />

area will remain forested, given <strong>the</strong> mountain terrain<br />

<strong>and</strong> political boundaries; however, development will<br />

continue in <strong>the</strong> lower elevation developable area.<br />

Monitoring tree canopy cover in <strong>the</strong> developable<br />

area keeps <strong>the</strong> focus on l<strong>and</strong>s most likely to change.<br />

The indicator was calculated by combining satellite<br />

<strong>and</strong> Geographic Information Systems (GIS) data for<br />

<strong>Burrard</strong> <strong>Inlet</strong> with a software model called CITYgreen to assess <strong>the</strong> quality <strong>and</strong> amount of forest in<br />

<strong>the</strong> <strong>Inlet</strong>. Map 2 (<strong>the</strong> aerial photograph in Section 1) provides an overview of l<strong>and</strong> use in <strong>Burrard</strong><br />

<strong>Inlet</strong>. Information on conditions such as rainfall, soil type, l<strong>and</strong> use, zoning <strong>and</strong> elevation is<br />

included. The model gives a measurement of tree canopy cover over <strong>the</strong> entire inlet, <strong>and</strong> allows a<br />

breakdown of l<strong>and</strong> cover type in <strong>the</strong> developable area.<br />

3 The boundary between developable <strong>and</strong> undeveloped l<strong>and</strong> is shown in Map 3 – 320 m elevation to <strong>the</strong> west of<br />

Lynn Creek (in North Vancouver) <strong>and</strong> 200 m to <strong>the</strong> east of Lynn Creek, consistent with Official Community Plans.<br />

This line places drinking water reservoirs <strong>and</strong> protected areas within <strong>the</strong> undeveloped area.<br />

Page | 12

<strong>Burrard</strong> <strong>Inlet</strong> <strong>Environmental</strong> <strong>Indicators</strong> <strong>Report</strong> February 2008<br />

Map 3: Developable vs. Undeveloped Areas for <strong>the</strong> <strong>Burrard</strong> <strong>Inlet</strong> Catchments<br />

Results <strong>and</strong> Trends<br />

Charts 1-1 <strong>and</strong> 1-2 illustrate types of l<strong>and</strong> cover for <strong>the</strong> <strong>Burrard</strong> <strong>Inlet</strong> watershed as a whole <strong>and</strong><br />

for developed versus undeveloped areas within <strong>the</strong> watershed, as measured in 2002 satellite<br />

imagery. This indicator will measure tree canopy in <strong>the</strong> developable area over time to assess<br />

how well communities balance <strong>the</strong>ir development plans with environmental <strong>and</strong> sustainability<br />

considerations.<br />

Page | 13

<strong>Burrard</strong> <strong>Inlet</strong> <strong>Environmental</strong> <strong>Indicators</strong> <strong>Report</strong> February 2008<br />

Chart 1-1: Current L<strong>and</strong> Cover across <strong>the</strong> Entire <strong>Burrard</strong> <strong>Inlet</strong> Watershed<br />

area (hectares)<br />

area (hectares)<br />

90,000<br />

80,000<br />

70,000<br />

60,000<br />

50,000<br />

40,000<br />

30,000<br />

20,000<br />

10,000<br />

0<br />

Trees Open space<br />

& shrub<br />

Trees Open space<br />

& shrub<br />

Water Urban Impervious<br />

surfaces<br />

Water Urban Impervious<br />

surfaces<br />

Considering <strong>the</strong> entire<br />

watershed (Chart 1-2), tree<br />

canopy, open space <strong>and</strong><br />

shrubs cover 88% of <strong>the</strong><br />

l<strong>and</strong>, reflecting <strong>the</strong> fact that<br />

76% of l<strong>and</strong> lies in <strong>the</strong><br />

forested upper l<strong>and</strong>s.<br />

In <strong>the</strong> undeveloped watershed,<br />

96% of l<strong>and</strong> is<br />

covered with trees <strong>and</strong> 3%<br />

with shrubs <strong>and</strong> grassy<br />

areas. The remaining 1%<br />

consists of water <strong>and</strong><br />

impervious cover (roads).<br />

Chart 1-2: Current L<strong>and</strong> Cover in Developable Areas of <strong>Burrard</strong> <strong>Inlet</strong><br />

12,000<br />

In <strong>the</strong> developable area<br />

(Chart 1-2), l<strong>and</strong> is<br />

10,000<br />

classified as 42% trees,<br />

8,000<br />

11% open<br />

shrubs, 4%<br />

space<br />

water,<br />

<strong>and</strong><br />

12%<br />

6,000<br />

impervious <strong>and</strong> 31%<br />

urbanized (commercial,<br />

4,000<br />

residential). A total of 53%<br />

2,000<br />

of developable l<strong>and</strong> is<br />

currently covered by trees,<br />

0<br />

shrubs <strong>and</strong> open space.<br />

Inner Harbour, 55% in Port Moody Arm <strong>and</strong> 84% in Indian Arm.<br />

Values for tree canopy in<br />

individual catchments are<br />

26% in English Bay, 26% in<br />

Tree canopy in <strong>the</strong> developable area will likely decline as <strong>the</strong> population continues to increase<br />

<strong>and</strong> l<strong>and</strong> continues to be developed.<br />

How does <strong>Burrard</strong> <strong>Inlet</strong> compare to existing targets <strong>and</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r localities?<br />

Comparing tree canopy data for <strong>the</strong> <strong>Burrard</strong> <strong>Inlet</strong> watershed to o<strong>the</strong>r regions can be useful.<br />

However, it is important to recognize <strong>the</strong> exceptional environmental setting of <strong>Burrard</strong> <strong>Inlet</strong> <strong>and</strong><br />

<strong>BIEAP</strong>’s goals of preserving <strong>the</strong> unique biodiversity <strong>and</strong> enhancing <strong>the</strong> environmental quality<br />

of our region when setting a target. Targets for tree canopy in urban areas range from 25 to<br />

40%, depending on population density, location <strong>and</strong> regional context. Examples from o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

jurisdictions include:<br />

• <strong>the</strong> CITYGreen model, with a suggested target of 50% for suburban residential (low<br />

density), 25% for urban residential (high density) <strong>and</strong> 15% for a central business area.<br />

• Toronto, Ontario, with a tree canopy target of 30% to 40% by 2020, <strong>and</strong> a current tree<br />

canopy of 17%<br />

• Portl<strong>and</strong>, Oregon, with 25% tree canopy cover <strong>and</strong> a goal of increasing this value.<br />

Page | 14

<strong>Burrard</strong> <strong>Inlet</strong> <strong>Environmental</strong> <strong>Indicators</strong> <strong>Report</strong> February 2008<br />

Tree cover in <strong>Burrard</strong> <strong>Inlet</strong> watershed is higher than for many o<strong>the</strong>r cities, with 42% canopy in<br />

<strong>the</strong> developable area <strong>and</strong> 11% shrubs <strong>and</strong> open space. This benchmark reflects <strong>the</strong> forested<br />

mountain slopes on <strong>the</strong> <strong>Inlet</strong>’s north shore, <strong>and</strong> should be protected as population growth<br />

continues. The lower tree canopy cover of 26% in developable areas of English Bay <strong>and</strong> Inner<br />

Harbour catchments indicates <strong>the</strong> loss of trees that tend to accompany urban growth.<br />

Economic benefits of tree cover<br />

Trees provide natural stormwater management, air purifying <strong>and</strong> climate control functions,<br />

assets that help municipalities balance <strong>the</strong>ir infrastructure costs. The CITYgreen model can<br />

generate information about <strong>the</strong> monetary value of ecosystem services provided by <strong>the</strong> tree<br />

canopy (Caslys 2006), as has been done by Metro Vancouver for its regional biodiversity<br />

assessment (AXYS 2006). Although assigning economic value to ecosystem services can<br />

divert attention from <strong>the</strong> non-monetary benefits, it does provide powerful information to<br />

decision-makers who manage infrastructure budgets.<br />

Based on <strong>the</strong> CITYgreen model, maintaining <strong>the</strong> current level of tree canopy in <strong>the</strong> 13,800 ha<br />

of developable area in <strong>Burrard</strong> <strong>Inlet</strong> will provide many economic savings, including:<br />

• $44M per year in tax dollars that would o<strong>the</strong>rwise be spent on stormwater infrastructure over<br />

<strong>the</strong> next twenty years (based on a comparison of <strong>the</strong> current condition vs. 0% tree canopy<br />

<strong>and</strong> $3,200 per hectare per year)<br />

• $6M per year for pollution removal (air pollutants such as nitrogen dioxide, sulphur dioxide,<br />

ozone, carbon monoxide <strong>and</strong> particulate matter; water pollutants such as nitrogen,<br />

phosphorus, suspended solids, metals, organic matter)<br />

• $1.2M for carbon storage <strong>and</strong> sequestration (carbon credits for preservation of existing trees<br />

equal to 89 tons per hectare)<br />

• additional savings in health care costs related to improved air quality.<br />

Fur<strong>the</strong>r information about <strong>the</strong> current status of air quality, greenhouse gas emissions <strong>and</strong><br />

water quality, <strong>and</strong> related issues in <strong>the</strong> <strong>Burrard</strong> <strong>Inlet</strong> watershed is provided in <strong>Indicators</strong> 4, 5<br />

<strong>and</strong> 6, respectively.<br />

What can we do to maintain or improve tree canopy cover?<br />

Changing our thinking to value trees as a public utility will be helpful during municipal<br />

budgeting <strong>and</strong> planning processes. O<strong>the</strong>r options include:<br />

• establishing a tree canopy goal as part of municipal development <strong>and</strong> maintenance projects<br />

• creating a formal process for measuring tree cover <strong>and</strong> recording data in <strong>the</strong> region’s GIS system<br />

• adopting policies, regulations <strong>and</strong> incentives to increase <strong>and</strong> protect <strong>the</strong> green infrastructure<br />

<strong>and</strong> to promote natural infiltration of rainwater<br />

• supporting installation of green roofs by providing incentives, development guidelines <strong>and</strong><br />

education<br />

• planting an appropriate mix of trees <strong>and</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r vegetation, along with adequate soil depths, in<br />

residential gardens<br />

For more information…<br />

• CITYgreen model: www.americanforests.org/resources/urbanforests/analysis.php<br />

• Green Roofs: www.greenroofs.org/, www.toronto.ca/greenroofs/index.htm,<br />

www.inhabit.com/2006/08/01/chicago-green-roof-program/<br />

• Tree Canopy Policy: www.fundersnetwork.org/usr_doc/Urban_Forests_FINAL.pdf<br />

Page | 15

<strong>Burrard</strong> <strong>Inlet</strong> <strong>Environmental</strong> <strong>Indicators</strong> <strong>Report</strong> February 2008<br />

2. Parks <strong>and</strong> Protected Areas<br />

Why look at parks <strong>and</strong> protected areas?<br />

The parks <strong>and</strong> protected areas indicator helps<br />

describe <strong>the</strong> overall health status of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Burrard</strong> <strong>Inlet</strong><br />

ecosystem. These areas include provincial, regional<br />

<strong>and</strong> municipal parks, protected drinking water<br />

watersheds <strong>and</strong> areas such as <strong>the</strong> Lower Seymour<br />

Conservation Reserve. The parks <strong>and</strong> protected<br />

areas in <strong>Burrard</strong> <strong>Inlet</strong> are managed to conserve fish<br />

<strong>and</strong> wildlife habitat, <strong>and</strong> to preserve natural <strong>and</strong> built<br />

environments for public use.<br />

Parks allow a range of recreational activities,<br />

Capilano Reservoir, Capilano River Regional Park<br />

including medium <strong>and</strong> high impact activities such<br />

as field sports, mountain biking <strong>and</strong> skiing, as well as lower impact hiking activities. Balanced<br />

l<strong>and</strong> use programming is important to ensure recreational activities do not have a negative effect<br />

on habitat.<br />

Current status: For <strong>the</strong> watershed as a whole, 66% of <strong>the</strong> l<strong>and</strong> has some measure of protection,<br />

<strong>and</strong> a fur<strong>the</strong>r 15% is in high elevation areas outside of <strong>the</strong> Metro Vancouver classification system,<br />

leaving 19% designated as residential <strong>and</strong> urban areas. Most of <strong>the</strong> protected l<strong>and</strong> is in <strong>the</strong><br />

undeveloped portion of <strong>the</strong> watershed (only 3% is residential or urban). The amount of protected<br />

l<strong>and</strong> in <strong>the</strong> developable area is 41% <strong>and</strong> varies for individual catchments.<br />

Using parks <strong>and</strong> protected areas as an indicator<br />

Parks <strong>and</strong> protected areas fall into three management classes,<br />

defined by Metro Vancouver, <strong>and</strong> Rockfish Conservation Areas,<br />

defined by Fisheries <strong>and</strong> Oceans Canada. These categories are<br />

described in Table 2-1, along with examples for each category.<br />

The indicator was developed by calculating <strong>the</strong> proportion of l<strong>and</strong> in<br />

each management class for <strong>the</strong> four main catchments in <strong>Burrard</strong><br />

<strong>Inlet</strong> for both developable <strong>and</strong> undeveloped areas (Map 4). The<br />

developable area (below <strong>the</strong> 320 m elevation to <strong>the</strong> west of Lynn<br />

Creek in North Vancouver, <strong>and</strong> 200 m to <strong>the</strong> east of Lynn Creek)<br />

includes suburban,<br />

urban <strong>and</strong> some<br />

protected areas.<br />

The undeveloped<br />

area at <strong>the</strong> higher<br />

Black Bear<br />

Protected areas conserve<br />

or manage habitat<br />

required for:<br />

• endangered, threatened,<br />

sensitive or vulnerable<br />

species<br />

• a critical life-cycle phase<br />

of a species, e.g.,<br />

spawning, rearing,<br />

nesting, or winter feeding<br />

• migration routes or o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

movement corridors<br />

• areas of very high<br />

productivity or species<br />

richness<br />

• recreational uses<br />