Download Complete Report (PDF 1.19mb) - RNIB

Download Complete Report (PDF 1.19mb) - RNIB

Download Complete Report (PDF 1.19mb) - RNIB

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

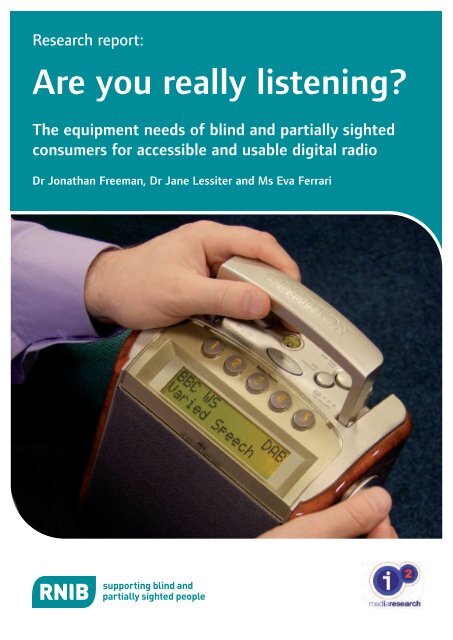

Research report:<br />

Are you really listening?<br />

The equipment needs of blind and partially sighted<br />

consumers for accessible and usable digital radio<br />

Dr Jonathan Freeman, Dr Jane Lessiter and Ms Eva Ferrari

Prepared for Royal National Institute of Blind People (<strong>RNIB</strong>) by Dr Jonathan Freeman,<br />

Dr Jane Lessiter and Ms Eva Ferrari<br />

i2 media research ltd<br />

Department of Psychology<br />

Goldsmiths<br />

University of London<br />

New Cross<br />

London<br />

SE14 6NW<br />

Telephone 020 7919 7884<br />

Fax 020 7919 7873<br />

Email j.freeman@gold.ac.uk<br />

Royal National Institute of Blind People (<strong>RNIB</strong>)<br />

Media and Culture Department<br />

105 Judd Street<br />

London<br />

WC1H 9NE<br />

Telephone 020 7388 1266<br />

Fax 020 7387 7109<br />

Email broadcasting@rnib.org.uk<br />

Project steering group:<br />

Heather Cryer<br />

Angela Edwards<br />

Anna Jones<br />

Shaun Leamon<br />

Leen Petré<br />

Cathy Rundle<br />

2

Foreword<br />

Foreword<br />

Access to radio is key to the quality of life of blind and partially sighted people.<br />

Research shows that listening to the radio is a favoured and valued pastime for many.<br />

Consumer digital radio equipment is able to provide listeners with a range of additional<br />

features and functions over analogue radio, including an increased choice of content<br />

through more stations, and the possibility of pausing live programmes as well as<br />

recording and playing back digital radio broadcasts.<br />

However, anecdotal evidence suggested to us that the needs of blind and partially<br />

sighted people were not met by existing digital radio equipment. In this context, the<br />

Royal National Institute of Blind People (<strong>RNIB</strong>) commissioned primary independent<br />

research from i2 media research limited to identify the equipment needs of blind and<br />

partially sighted consumers for usable and accessible digital radio equipment. In<br />

addition, we wanted to compare those needs to those of sighted control groups and<br />

people with dexterity problems and dyslexia. The result is a fascinating report that<br />

highlights the many similarities between the needs of these different consumer groups<br />

and that provides designers of digital radio equipment with a set of very precise design<br />

recommendations that should enable them make their products more user-friendly and<br />

accessible.<br />

As a second tier to this project, <strong>RNIB</strong> has also commissioned Ricability to conduct a<br />

comparative evaluation of currently available DAB equipment against the design<br />

checklist, to fully assess what the precise state of the market is with regards to<br />

usability and accessibility and advise consumers on purchase decisions.<br />

This i2 Media research report shows that equipment design can be improved<br />

considerably, and that some significant changes are relatively easy to implement for<br />

the product chain. <strong>RNIB</strong> is keen to make the design recommendations from this<br />

research happen. This report is therefore an open invitation to manufacturers, retailers,<br />

representative UK and European industry bodies, regulators and the UK government to<br />

make the digital radio experience of blind and partially sighted people a better one,<br />

and we are grateful to those who have already started that journey with us.<br />

Leen Petré<br />

Principal Manager, Media and Culture Department, <strong>RNIB</strong><br />

3

Executive summary<br />

1. Aims<br />

The research questions addressed in the project were:<br />

1. What are the core functional requirements of blind and partially sighted people<br />

from consumer digital radio equipment?<br />

2. What are the design considerations required to make the more advanced functions<br />

of current and emerging consumer digital radio equipment accessible to blind and<br />

partially sighted people?<br />

3. What are the accessibility and usability priorities for accessible and easy to use<br />

consumer digital radio equipment for blind and partially sighted people?<br />

4. To what extent (and how) are accessibility considerations built into manufacturers’<br />

product design and development processes of consumer digital radio equipment?<br />

Within this context, how feasible is it for manufacturers to develop consumer<br />

digital radio equipment that is accessible to blind and partially sighted people?<br />

2. Methods<br />

To address the above research questions, the project involved both consumer and<br />

industry research.<br />

The consumer research comprised two activities:<br />

1. Qualitative in-depth research in the homes of 38 Digital Audio Broadcasting (DAB)<br />

radio consumers around the UK (24 blind and partially sighted consumers, 3<br />

consumers with dyslexia, 3 with reduced dexterity, and 8 ‘sighted control’<br />

participants). Participants were interviewed and observed using familiar and<br />

unfamiliar DAB equipment during these sessions. The goal of this activity was to<br />

gain an in-depth understanding of the needs of blind and partially sighted people<br />

in terms of maximising the accessibility and usability of consumer digital radio<br />

equipment. In addition, the research aimed to assess how the digital radio<br />

equipment needs of blind and partially sighted people compared with those of<br />

sighted people, people with dyslexia and people with dexterity impairments.<br />

4

Executive summary<br />

2. A telephone-based survey (Short Preference Survey) involving 325 DAB users (a<br />

sample of 100 blind and partially sighted DAB users, and a nationally<br />

representative control sample of 225 DAB users). The goal of this activity was to<br />

evaluate the extent to which current DAB radios support independent use by blind<br />

and partially sighted consumers, compared with sighted consumers, and to<br />

highlight any similarities and differences.<br />

The industry research involved the project researchers conducting in-depth interviews<br />

with six senior representatives of manufacturers and other entities in the consumer<br />

DAB equipment supply chain. The majority of these interviews were conducted faceto-face,<br />

though two were conducted via the telephone. The goal of the industry<br />

interviews was to find out how participant companies currently research user needs,<br />

the extent to which the needs of blind and partially sighted consumers are researched<br />

and/or understood by participant companies, and what the industry sees as barriers for<br />

addressing the needs of blind and partially sighted consumers.<br />

3. Main findings<br />

3.1 Blind and partially sighted users tend to be more reliant on radio than<br />

sighted users<br />

Consistent with much of the background literature reviewed in the project, access<br />

to radio was revealed in both the project’s qualitative and quantitative research as<br />

more important to blind and partially sighted participants than to sighted<br />

participants. Blind and partially sighted participants were more likely to refer to<br />

listening to the radio as their favoured pastime.<br />

3.2 There are clear benefits for sighted consumers when the equipment needs of<br />

people with sight problems are addressed<br />

Many of the usability and accessibility issues which affected blind and partially<br />

sighted participants’ use of DAB equipment were also observed to reduce usability<br />

for sighted participants. Addressing the design considerations should improve the<br />

user experience of digital radio equipment for all groups: blind, partially sighted<br />

and sighted consumers. The top level design considerations relate to button<br />

feedback, button design, physical properties of the text display and interface<br />

software design.<br />

5

Executive summary<br />

3.3 Limited interest in and concerns about advanced functions<br />

Many blind, partially sighted and sighted participants showed no interest in<br />

advanced features, either because they felt they had no need for them or they<br />

currently used and were comfortable with alternative methods for features such as<br />

recording. Many blind and partially sighted participants expressed concern that<br />

advanced features were not accessible to them because these features rely heavily<br />

on the text display.<br />

3.4 Voice output greatly increases the ability of blind and partially sighted<br />

consumers to use digital radio equipment as independently as sighted<br />

consumers<br />

A major difference between how blind and partially sighted and sighted consumers<br />

use DAB radio is whether or not they can use their equipment independently. The<br />

research revealed that blind and partially sighted people can use radios with voice<br />

output more independently than they can use radios without voice output. Voice<br />

output provides audible (synthetic or recorded) speech feedback to the user in one<br />

or both of two ways. First a voice can confirm via speech, the buttons that a user<br />

presses or functions that a user alters. Second, a voice can read out the<br />

information that appears on the radio’s text display (eg station name, time, genre).<br />

Comparing matched samples, relative to sighted DAB users, blind and partially<br />

sighted users who do not have voice output on their radio were twice as likely to<br />

report needing help from another person to use their DAB radio. At first use, 90<br />

per cent of blind and partially sighted participants who were using a DAB radio<br />

without voice output reported needing help from someone else. This contrasted<br />

significantly with the much lower figure of 39 per cent of the nationally<br />

representative sample reporting needing help. For subsequent use of DAB radio,<br />

blind and partially sighted participants using a DAB radio without voice output<br />

were again significantly more likely than the nationally representative sample to<br />

report needing help (69 per cent versus 17 per cent).<br />

However, a much lower figure, namely 48 per cent of blind and partially sighted<br />

participants reporting on radios with voice output needed help from someone else<br />

at first use, and 26 per cent needed help for subsequent use. Voice output<br />

provided a level playing field, as these figures were not significantly different to<br />

those for the nationally representative sample. However, the numbers needing help<br />

were significantly higher for those blind and partially sighted participants reporting<br />

on use of a DAB radio without voice output.<br />

6

Executive summary<br />

Comparison of survey responses from blind and partially sighted consumers<br />

describing their use of DAB radios with and without voice output clearly<br />

demonstrates the high value of voice output for blind and partially sighted<br />

consumers. More blind and partially sighted users of digital radio with voice output<br />

report being able to use their radios independently than do blind and partially<br />

sighted users of digital radio without voice output.<br />

3.5 Barriers to better addressing the needs of blind and partially sighted<br />

consumers cited by industry interviewees centred largely on pragmatic and<br />

commercial considerations<br />

Industry representatives from the consumer DAB equipment supply chain cited a<br />

range of commercial barriers to addressing accessibility issues, including: difficulty<br />

evidencing return on investment (and thus building a compelling business case);<br />

concerns that building in accessibility may be off-putting to the core (mainstream)<br />

market; and that previous attempts at marketing accessible products have rarely<br />

been successful.<br />

Potential solutions suggested by interviewees included improved industry<br />

consultation with stakeholders, better access to research on user needs (where this<br />

report should fill the gap), actionable advice about how to improve accessibility<br />

(again a gap filled by this report), consumer education, and technical<br />

developments.<br />

4. Key Project Output: prioritised design checklist<br />

Through analysis of the project’s in-depth interviews and videos of participants using<br />

their own and unfamiliar digital radio equipment, an inventory of design considerations<br />

was developed within the project. This was developed into a prioritised checklist (see<br />

Chapter 9) as a design resource, and is also being used in a related activity<br />

commissioned by <strong>RNIB</strong> from Ricability, namely an evaluation of a range of DAB<br />

equipment on the market against the checklist.<br />

The checklist items were prioritised by considering factors such as the range of tasks<br />

that could be affected by addressing the design consideration, the frequency of tasks,<br />

and whether they were involved in basic use such as switching on, changing station,<br />

and changing volume.<br />

7

Executive summary<br />

The full checklist is presented in Chapter 9. Highest priority items relate to best<br />

practice in:<br />

the provision of button feedback (including voice output)<br />

button design (including size, groupings and spacing)<br />

physical properties of the text display (including contrast and size) to make it more<br />

readable, and<br />

interface software design to minimise user intervention or to maximise simplicity of<br />

user interaction and to provide intuitive processes (eg for autotune, rescan, scroll,<br />

select, play recording)<br />

The research findings and design considerations were presented to industry at an<br />

interim juncture in the project. The project team received feedback that many of the<br />

checklist items are easily addressable by manufacturers in the product development<br />

process.<br />

5. Next steps to support the availability of more<br />

accessible digital radio equipment<br />

It is <strong>RNIB</strong>’s intention that this research report, including the digital radio interface<br />

design checklist developed within the project, in conjunction with the comparative<br />

evaluation of currently available DAB equipment against the checklist, will support the<br />

availability of digital radio equipment that better meets the needs of blind, partially<br />

sighted and sighted consumers.<br />

In further pursuit of this goal, <strong>RNIB</strong> is engaged with manufacturers, others in the<br />

supply chain, UK and European industry and statutory bodies.<br />

8

Contents<br />

1. Radio and blind and partially sighted people - background ______________15<br />

1.1. Radio listening is a valued leisure activity __________________________15<br />

1.2. Range of radio content consumed ________________________________16<br />

1.3. Range of stations listened to ____________________________________16<br />

1.4. Changing station with analogue radio equipment ____________________16<br />

1.5. Confidence with technology ____________________________________16<br />

1.6. Accessibility is an important consideration __________________________17<br />

1.7. Usability and accessibility issues __________________________________17<br />

1.8. Switchover to digital radio ______________________________________18<br />

1.9. Access to digital radio – an <strong>RNIB</strong> focus ____________________________18<br />

2. Aims and objectives: scope of work__________________________________19<br />

2.1. Research questions ____________________________________________19<br />

3. Methodology ____________________________________________________21<br />

3.1. Consumer research: in-depth interviews ____________________________21<br />

3.1.1. Rationale ____________________________________________21<br />

3.1.2. Sample ______________________________________________22<br />

3.1.3. Procedure ____________________________________________27<br />

3.2. Consumer research: Short Preference Survey ________________________28<br />

3.2.1. Rationale ____________________________________________28<br />

3.2.2. Sample for the Short Preference Survey ______________________28<br />

3.2.3. Procedure ____________________________________________31<br />

3.2.4. Methodology for assessing impact of voice output ____________34<br />

3.3. Industry research: semi-structured interviews________________________34<br />

3.3.1. Rationale ____________________________________________34<br />

3.3.2. Sample ______________________________________________34<br />

3.3.3. Procedure ____________________________________________35<br />

4. Structure of results chapters ______________________________________36<br />

9

Contents<br />

5. Setting the scene ________________________________________________38<br />

5.1. Personas ____________________________________________________38<br />

5.2. Independence, disability, and sense of exclusion (blind and partially sighted<br />

sample) ____________________________________________________43<br />

5.3. Value of radio (all samples)______________________________________44<br />

5.4. Ownership of radio (all samples)__________________________________46<br />

5.5. The meaning of ‘digital radio’ (all samples) ________________________49<br />

6. Core functional requirements ______________________________________50<br />

6.1. Summary____________________________________________________50<br />

6.2. Blind and partially sighted people: general use of DAB radios __________51<br />

6.2.1. Time spent listening to radio ______________________________51<br />

6.2.2. Reliance on radio for news ________________________________52<br />

6.2.3. Range of radio stations listened to__________________________52<br />

6.2.4. Expectations of DAB ____________________________________53<br />

6.2.5. Exploration of unfamiliar stations __________________________53<br />

6.3. Sighted controls and participants with dyslexia and manual dexterity<br />

impairment: general use of DAB radio ____________________________53<br />

6.3.1. Time spent listening to radio ______________________________53<br />

6.3.2. Reliance on radio for news ________________________________54<br />

6.3.3. Range of radio stations listened to__________________________54<br />

6.3.4. Expectations of DAB ____________________________________54<br />

6.3.5. Exploration of unfamiliar stations __________________________55<br />

6.4. Blind and partially sighted people: operating DAB radios ______________55<br />

6.4.1. More difficulties in operating equipment ____________________55<br />

6.4.2. Troubleshooting ________________________________________56<br />

6.4.3. Ease-of-use __________________________________________57<br />

6.4.4. Confidence with technology ______________________________57<br />

6.4.5. Variation in interface design for DAB radios __________________57<br />

6.4.6. Strategies for learning to use DAB radios ____________________58<br />

6.4.7. Simple strategies for everyday use of DAB radios ______________58<br />

6.4.8. Good feedback valued __________________________________59<br />

6.5. Sighted people: operating DAB radios ____________________________59<br />

6.5.1. Limited impact of dyslexia or dexterity impairment ____________59<br />

10

Contents<br />

6.5.2. Confidence with technology ______________________________60<br />

6.5.3. Feedback and buttons __________________________________60<br />

6.5.4. Context based similarities in blind, partially sighted and sighted<br />

users’ needs __________________________________________60<br />

6.6. Core functions of DAB radio use ________________________________61<br />

6.7. Equipment considerations that make core functionality accessible to blind and<br />

partially sighted consumers ____________________________________61<br />

6.7.1. Feedback from equipment ________________________________61<br />

6.7.2. Physical characteristics of buttons __________________________62<br />

6.7.3. Physical properties of the text display ______________________65<br />

6.7.4. Default software processes________________________________67<br />

6.7.5. Instruction manuals ____________________________________68<br />

6.7.6. Packaging, hardware and basic connections for set up __________70<br />

6.7.7. Interaction design ______________________________________71<br />

6.7.8. Remote control interfaces ________________________________72<br />

6.8. Applicability of design considerations for use by people with sight ______72<br />

6.8.1. Feedback ____________________________________________72<br />

6.8.2. Physical characteristics of buttons __________________________73<br />

6.8.3. Physical properties of the text display ______________________74<br />

6.8.4. Default software processes________________________________75<br />

6.8.5. Instruction manuals ____________________________________75<br />

6.8.6. Packaging, hardware and basic connections for set up __________75<br />

6.8.7. Interaction design ______________________________________76<br />

6.8.8. Remote control interfaces ________________________________77<br />

7. Advanced functions ______________________________________________78<br />

7.1. Summary____________________________________________________78<br />

7.2. Blind and partially sighted people’s interest in advanced functions of<br />

DAB radio __________________________________________________78<br />

7.2.1. Advanced features were not spontaneously associated with<br />

DAB radio ____________________________________________78<br />

7.2.2. Mixed reaction to advanced features of DAB radio ____________79<br />

7.3. Sighted people’s interest in advanced functions of DAB radio __________81<br />

7.3.1. Mixed reaction to advanced features of DAB radio ____________81<br />

7.3.2. Use of digital audio alternatives to advanced DAB functions ______82<br />

11

Contents<br />

7.4. Survey respondents’ prioritisation of advanced DAB features____________82<br />

7.5. Equipment considerations to make advanced functionality accessible to<br />

blind and partially sighted consumers______________________________85<br />

7.5.1. Features specified in relation to core functionality are important<br />

for making advanced functions accessible ____________________85<br />

7.5.2. Characteristics of the text display and voice output ____________85<br />

7.5.3. Concerns about voice output for advanced features ____________86<br />

7.5.4. Customisation of voice output for advanced features____________86<br />

7.5.5. Voice output as default __________________________________86<br />

7.5.6. Natural sounding voice output ____________________________86<br />

7.6. Equipment considerations for usability of advanced functionality for sighted<br />

consumers __________________________________________________87<br />

8. Consumer reaction to voice output __________________________________88<br />

8.1. Summary____________________________________________________88<br />

8.2. Overwhelmingly positive feedback ________________________________88<br />

8.3. Interest in adoption of DAB radios with voice output__________________89<br />

8.4. Voice output and blind and partially sighted respondents’ independent<br />

use of DAB radio ____________________________________________90<br />

8.4.1. Sighted respondents more likely to report independent DAB<br />

radio use______________________________________________90<br />

8.4.2. Voice output increases extent of independent use for blind and<br />

partially sighted respondents ______________________________91<br />

8.4.3. Voice output reduced extent of help needed by blind and partially<br />

sighted respondents ____________________________________92<br />

8.4.4. Voice output reduced reports of difficulties __________________93<br />

8.4.5. Voice output reduced reliance on others to help with difficulties __95<br />

8.4.6. Voice output increased blind and partially sighted respondents<br />

awareness of their radio’s functionality ______________________97<br />

8.4.7. Perceived limitations of voice output ________________________98<br />

8.5. Voice output and perceived ease of use ____________________________98<br />

8.5.1. Voice output is a major benefit to blind and partially sighted<br />

participants____________________________________________98<br />

8.5.2. Voice output DAB radios easy to use ________________________99<br />

8.5.3. Voice output DAB radio owners more likely to agree DAB is easier to<br />

use than analogue radio ________________________________100<br />

12

Contents<br />

9. Priorities for accessible and usable DAB radios for blind and partially sighted<br />

people ________________________________________________________102<br />

9.1. Summary __________________________________________________102<br />

9.2. The checklist and priority levels ________________________________103<br />

10. Insights from DAB industry interviews ______________________________110<br />

10.1. Research questions __________________________________________110<br />

10.2. Motivation for the industry interviews ____________________________110<br />

10.3. Main themes observed ________________________________________110<br />

10.3.1. Partnerships with representative groups and charities __________110<br />

10.3.2. Representative groups – a useful source of insight ____________111<br />

10.3.3. No direct research on needs of blind and partially sighted people from<br />

digital radio __________________________________________111<br />

10.3.4. Concerns about return on investment ______________________111<br />

10.4. Solutions discussed by industry interviewees ______________________112<br />

10.4.1. Better interfaces with representative groups and charities ______112<br />

10.4.2. Current limited research on the needs of blind and partially<br />

sighted people ________________________________________112<br />

10.4.3. Improved confidence that a market exists __________________113<br />

10.4.4. Consumer education and information ______________________113<br />

10.4.5. Technical developments over time cited as most probable<br />

solutions ____________________________________________114<br />

10.4.6. Levers to speed up change: international standards and<br />

procurement __________________________________________114<br />

10.4.7. Lukewarm reactions to any new legislation or regulation ________114<br />

11. Conclusions ____________________________________________________115<br />

11.1. Blind and partially sighted users are more reliant on radio than are<br />

sighted users________________________________________________115<br />

11.2. Simple design considerations could improve access __________________115<br />

11.3. Current limited interest in, and concerns about, advanced functions ____115<br />

11.4. Industry is engaging with evidence-based prioritisation of design<br />

considerations ______________________________________________115<br />

11.5. Many of the design considerations are relatively easily addressed ______116<br />

11.6. Addressing the needs of people with sight problems has benefits for sighted<br />

consumers__________________________________________________116<br />

13

Contents<br />

11.7. Voice output enables blind and partially sighted consumers to use digital<br />

radio equipment almost as independently as sighted consumers ________116<br />

11.8. Industry cites pragmatic and commercial barriers __________________117<br />

11.9. Industry would benefit from better availability of research insight,<br />

interaction with stakeholders and consumer awareness ______________117<br />

11.10. <strong>RNIB</strong> is supporting better consumer information ____________________117<br />

11.11. <strong>RNIB</strong> is supporting the availability of more accessible digital radio<br />

equipment, in this and future work ______________________________118<br />

12. Acknowledgements ______________________________________________119<br />

13. Bibliography____________________________________________________120<br />

14. Glossary of terms________________________________________________121<br />

Appendix A: Short Preference Survey on DAB use<br />

______________________122<br />

Appendix B: Data tables ____________________________________________136<br />

14

1. Radio and blind and partially sighted<br />

people – background<br />

This document reports primary independent research conducted by i2 media research<br />

limited (i2) and commissioned by <strong>RNIB</strong>, to identify what makes digital radio equipment<br />

accessible and ensures it meets the needs of blind and partially sighted consumers.<br />

Whilst the research reported here focuses on DAB radio equipment, it is important to<br />

note that basic user actions are broadly similar for other types of stand-alone digital<br />

radio receiver equipment. These actions include switching the device on and off,<br />

selecting station, and changing volume. Consequently, the equipment needs identified<br />

through the current research apply to interface design for other stand-alone equipment<br />

that can receive multi-channel digital radio. For example stand-alone internet radios<br />

and radios that belong to the wider digital radio standards family (such as DAB+), but<br />

excluding PC and digital TV interfaces.<br />

Before starting the primary research, a review was conducted of previous relevant<br />

research. Key findings from the review are presented below.<br />

1.1. Radio listening is a valued leisure activity<br />

Previous research has shown that listening to radio is a highly valued pastime of<br />

blind and partially sighted people (Douglas, Corcoran and Pavey, 2006; <strong>RNIB</strong> DAB<br />

Development <strong>Report</strong>, 2000; Bruce, McKennell and Walker, 1991). Douglas et al. (2006)<br />

reported that over 90 per cent of blind and partially sighted participants in their<br />

Network 1000 research on the opinions and circumstances of visually impaired people<br />

in Britain regularly listened to the radio and music. Almost half of these participants<br />

mentioned without prompting that they regularly listen to radio, the remainder<br />

mentioned radio on prompting. In the same study a high but slightly lower percentage<br />

of participants reported regularly watching television (87 per cent). As the Network<br />

1000 research reported, for participants with sight problems the “most popular<br />

at-home leisure activity was listening to the radio or to music (91 per cent),<br />

followed by listening to/watching television or videos/DVDs (87 per cent), and<br />

reading/listening to Talking Books (77 per cent)”. This finding was similar across the<br />

wide age range sampled in the Network 1000 study, and the popularity of radio was<br />

not related to degree of sight loss.<br />

In their study, Bruce, McKennell and Walker (1991) reported that over 80 per cent of<br />

blind and partially sighted people own and listen to radio, and that a further 10 per<br />

cent own a radio but do not listen to it. In this study, they observed an age trend, in<br />

15

1. Radio and bind and partially sighted people – background<br />

that older participants (aged 75+) were more likely than younger participants to report<br />

not owning or listening to the radio.<br />

1.2. Range of radio content consumed<br />

Though their study was conducted before the advent of digital radio before there was<br />

the additional choice offered by digital radio, Bruce et al. (1991) reported that blind<br />

and partially sighted people listen to a broad range of content. Participants were asked<br />

which one radio station they listened to most out of BBC Radio 1, 2, 3, 4, local radio<br />

(BBC and commercial), local radio for blind people, and other. Across all participants,<br />

local radio, BBC Radio 2 and BBC Radio 4 were the three most often selected options.<br />

Preferences were broadly similar across all age groups, though there was a tendency for<br />

local radio to be preferred by younger participants.<br />

1.3. Range of stations listened to<br />

Bruce et al’s (1991) study also asked participants which of the radio stations from the<br />

above list they ever listened to. Overall, 50 per cent reported sometimes listening to<br />

local radio, 43 per cent to BBC Radio 2, 36 per cent to BBC Radio 4, and 15 per cent<br />

to both BBC Radio 1 and Radio 3. This pattern of results reflects the older age profile<br />

of blind and partially sighted people relative to that of the general UK population.<br />

Given that the number of stations available to listeners has increased substantially<br />

since their study, particularly with the advent of digital radio broadcasting, the findings<br />

of Bruce et al (1991) that blind and partially sighted people tend to listen to more<br />

than one radio station is particularly relevant background to the current research.<br />

1.4. Changing station with analogue radio equipment<br />

The study by Bruce et al (1991) explored how blind and partially sighted people<br />

reported that they change station to listen to a different radio station, using analogue<br />

radio equipment. They reported that 77 per cent of participants aged under 60 years<br />

and 62 per cent of those aged 75 years and above, changed station themselves.<br />

1.5. Confidence with technology<br />

For older participants, the extent of residual vision was observed to have an impact on<br />

whether they reported being able to change station themselves. The same effect was<br />

not observed in relation to younger participants. Whilst Bruce et al. (1991) did not<br />

make this explicit, this finding suggests that participants’ confidence in using their<br />

16

1. Radio and bind and partially sighted people – background<br />

analogue radio equipment was an important consideration in understanding their<br />

usage behaviours. This is consistent with more recent research the i2 media research<br />

team has conducted on consumer use of domestic media technologies, including<br />

digital television and computers (Ofcom, March 2006). In any event, the findings from<br />

Bruce et al. (1991), and the Network 1000 research (Douglas et al. 2006) demonstrate<br />

the importance of considering the ease of use and accessibility to blind and partially<br />

sighted people of radio equipment.<br />

1.6. Accessibility is an important consideration<br />

Digital radio provides consumers with a greater choice of radio content than analogue<br />

radio. A choice that is appreciated by many, as evidenced by recent data from Ofcom<br />

(Ofcom, 2008b) showing a continuous growth in take up of DAB radio equipment by<br />

UK consumers. Further take up is likely to be supported by new feature releases in<br />

consumer digital radio equipment. New equipment is able to provide listeners with a<br />

range of new features and functions, including the possibility of pausing and recording<br />

live digital radio broadcasts, iPod docking, and integration with internet radio (via inhome<br />

wireless broadband internet, Wi-Fi). Ongoing research by the Digital Radio<br />

Development Bureau (2007) indicates interest in various of these functions amongst<br />

current and potential digital radio listeners.<br />

The development of interfaces for other digital media equipment, such as digital<br />

television receivers, demonstrates that they, relative to their analogue equivalents,<br />

have more complex interfaces enabling users to use the increased functions for using<br />

digital media services. Examples with digital radio equipment include menus and<br />

electronic programme guides presented visually.<br />

1.7. Usability and accessibility issues<br />

Concurrent with this project, Ofcom conducted a research study on the experiences of<br />

blind and partially sighted people with a range of communications services (Ofcom,<br />

July 2008). With regard to radio, the study reported that there were some usability or<br />

accessibility features that were particularly appreciated by blind and partially sighted<br />

people. The report noted that blind and partially sighted people have specific<br />

strategies to change station such as by memory, or touch or waiting until a station<br />

name announcement. The Ofcom research also reported that people with more severe<br />

sight loss most appreciated digital radio equipment that reads out the channel name.<br />

On the whole, navigation of stations using a remote control (accessing digital radio via<br />

digital television set top boxes) was reported by participants as the easiest way of<br />

selecting what to listen to. As its scope covered blind and partially sighted people’s<br />

17

1. Radio and bind and partially sighted people – background<br />

experiences of several communications services, the depth of focus the Ofcom study<br />

was able to give to radio use was more limited than that afforded by the current<br />

project.<br />

1.8. Switchover to digital radio<br />

If a switchover to digital radio takes place at any stage, like the digital television<br />

switchover process, digital radio would be the only way to receive the major public<br />

service and commercial radio channels. This is a factor accentuating the importance of<br />

supporting access for blind and partially sighted people to digital radio equipment.<br />

1.9. Access to digital radio – an <strong>RNIB</strong> focus<br />

Listening to the radio is important to blind and partially sighted people and so<br />

accessibility and usability of consumer digital radio equipment is of high importance<br />

(eg Douglas et al., 2006). A concern of <strong>RNIB</strong> is that a valued existing pastime<br />

(listening to the radio) and the benefits of new and emerging features and functions<br />

should be as accessible to blind and partially sighted consumers, as they are to sighted<br />

consumers.<br />

In this context, the current research was commissioned by <strong>RNIB</strong> to identify equipment<br />

design considerations to support accessibility to digital radio by blind and partially<br />

sighted consumers.<br />

The aims and objectives of the current research, and the research questions addressed<br />

in it are described in Chapter 2.<br />

The research methods used (in home in depth interviews and telephone interviews with<br />

blind, partially sighted and sighted consumers, and semi-structured interviews with<br />

representatives from the consumer digital radio equipment supply chain) and the<br />

research participants sampled are described in detail in Chapter 3.<br />

Chapters 4 to 10 present the results of both the consumer research activities, and the<br />

industry interviews, including the full consumer digital radio equipment design<br />

consideration checklist (in Chapter 9).<br />

The report conclusions are presented in Chapter 11, and finally, the Appendices include<br />

the questionnaire used for the project’s Short Preference Survey, and table format<br />

presentations of all charted data.<br />

18

2. Aims and objectives: scope of work<br />

In January 2008, <strong>RNIB</strong> commissioned detailed primary user and industry research into<br />

DAB digital radio. The project was initiated in recognition that the consumer digital<br />

radio equipment market is fast developing and that monitoring the accessibility of<br />

digital radio products currently used by blind and partially sighted people might help<br />

guide design for easier to use products in the future.<br />

The key objective of the research project was to gain an in-depth understanding of the<br />

needs of blind and partially sighted people for consumer digital radio equipment, and<br />

to establish how these needs differ from those of sighted radio listeners. An<br />

understanding of these needs is a precursor to improving the accessibility and usability<br />

of consumer digital radio equipment. A second objective of the research was to<br />

understand the extent to which the consumer electronics industry is able and likely to<br />

meet these needs.<br />

The scope of this research is limited to considerations relating to table top and<br />

portable digital radio equipment. However, it has wider relevance because basic user<br />

actions are by definition broadly similar for different types of standalone digital radio<br />

receiver equipment. These actions include switching the device on and off, selecting<br />

station and changing volume. For this reason, the equipment needs identified through<br />

the current research are applicable to interface design for other stand-alone equipment<br />

that can receive multi-channel digital radio, such as stand-alone internet radios and<br />

radios that belong to the wider digital radio standards family (such as DAB+), but<br />

excluding PC and digital TV interfaces for listening to digital radio.<br />

2.1. Research questions<br />

To address the key objective, a series of research questions were established.<br />

These were as follows:<br />

1. What are the core functional requirements from consumer digital radio equipment<br />

for blind and partially sighted people, and how do these compare with those of the<br />

control group?<br />

2. What are the design considerations needed to make the more advanced functions of<br />

current and emerging consumer digital radio equipment accessible to blind and<br />

partially sighted people? How do these compare with those of the control group?<br />

3. What are the accessibility and usability priorities for accessible and easy to use<br />

consumer digital radio equipment for blind and partially sighted people? How do<br />

these compare with those of the control group?<br />

19

2. Aims and objectives: scope of work<br />

And in relation to the DAB equipment supply chain:<br />

4. To what extent and how are accessibility considerations built into the product design<br />

and development processes by manufacturers of consumer digital radio equipment?<br />

5. In this industry context, how feasible is it for manufacturers to develop consumer<br />

digital radio equipment that is accessible to blind and partially sighted people, and<br />

what constraints, if any, are cited that limit feasibility?<br />

The scope of the first research question about the core functional requirements for<br />

blind and partially sighted people included: the range of current usage scenarios with<br />

digital radio (ie what people generally want to do with digital radio; techniques used to<br />

operate consumer digital radio equipment; and how easy to use and accessible these<br />

functions are with current equipment). Blind, partially sighted and sighted participants’<br />

experiences are compared to understand the extent to which there is any evidence that<br />

shows that poor usability of DAB radios can be a barrier.<br />

Areas considered in the scope of research questions 2 and 3 , included: ease of tuning,<br />

legibility of any screen menus and information, dependence on screen usage, physical<br />

manipulation of controls, visibility of labelling, ease of understanding the logic of<br />

controls and settings, and any other areas identified in the primary research conducted<br />

with DAB users. Particular design features relevant to tasks that are considered to be<br />

core or frequently used ‘basic functions’, informed a list of prioritised design features.<br />

The scope of research questions 4 and 5 about the industry includes current practices<br />

in product development. This includes industry standards for product design, and the<br />

extent to which any user testing for accessible or usable design is conducted. Research<br />

considerations included the following: technical feasibility; investment costs required<br />

(research and development, marketing); potential return on investment including the<br />

extent to which solutions could be applied beyond the UK market.<br />

The extent to which good practice in relation to design for accessibility conducted in<br />

other industries such as digital TV, fixed and mobile telephony is transferable to the<br />

research and development and product development activities of DAB manufacturers<br />

was also considered.<br />

In the next chapter, the methods used to address these research questions are<br />

described.<br />

20

3. Methodology<br />

3. Methodology<br />

To understand the experiences of, and requirements from DAB radio equipment for<br />

blind and partially sighted users’, a multi-method, multi-perspective approach was<br />

adopted, using both qualitative and quantitative approaches. Industry interviews were<br />

conducted to understand perceived incentives, hurdles and barriers to industry<br />

addressing these consumer needs.<br />

There were two target samples for the research: DAB consumers and industry.<br />

The methods used for these groups were as follows:<br />

For the consumer research:<br />

In-depth interviews<br />

Structured Short Preference (telephone) Survey.<br />

For the industry research:<br />

Semi-structured interviews.<br />

3.1. Consumer research: in-depth interviews<br />

3.1.1. Rationale<br />

Thirty-eight in home, in depth interviews were conducted with DAB radio users to<br />

identify any difficulties blind, partially sighted and sighted people experience in<br />

operating DAB radio. This method was selected to inform research questions 1-3<br />

(see Section 2.1).<br />

In home, indepth interviews were selected to support the collection of rich data.<br />

The rationales for selecting this method were that:<br />

(a) Participants are interviewed in familiar and comfortable contexts, less daunting<br />

than more formal contexts, which should put participants at ease with discussing the<br />

research topics.<br />

(b) The researcher can easily compare (through careful observation) what participants<br />

say they do with their radio with how they demonstrate they use it (catering for any<br />

bias in self reporting).<br />

(c) The semi-structured questioning approach allows considerable flexibility in the<br />

discussion allowing the researcher to probe further when required and identify areas<br />

that may have been overlooked in the discussion guide.<br />

21

3. Methodology<br />

The results of this method informed the development of a prioritised checklist that<br />

identifies design considerations for DAB radio to increase its accessibility to blind and<br />

partially sighted users (see Chapter 9).<br />

3.1.2. Sample<br />

In-depth interviews were conducted with four groups of participants.<br />

People who are blind or partially sighted (‘BPS’: n=24)<br />

People with dyslexia (‘dyslexia’: n=3)<br />

People with manual dexterity problems (‘dexterity’: n=3)<br />

People who report none of the above (‘sighted controls’; n=8)<br />

The research participants with dyslexia and manual dexterity problems and the sighted<br />

controls were recruited to compare their DAB radio experiences with those of the blind<br />

and partially sighted participants. The dyslexia and manual dexterity samples were<br />

small (n=3) and were not a fully representative sample (eg across age) and conclusions<br />

based on this sample size should be treated with caution. Nevertheless they were<br />

included to give the research the opportunity to identify major differences or<br />

similarities with the blind and partially sighted sample. For instance, aspects of the<br />

design (eg scrolling text) may cause similar accessibility issues for people with dyslexia.<br />

Similarly, button size, shape, spacing and press mechanism may affect usability for<br />

people with manual dexterity problems as well as for blind and partially sighted people.<br />

Furthermore, DAB radio design features that may cause accessibility difficulties for<br />

blind and partially sighted people might also affect usability in a sighted control<br />

sample, limiting their use of DAB radio functions.<br />

To ensure that a variety of DAB radio use experiences were identified a range of blind<br />

and partially sighted participants with different levels of sight loss were recruited.<br />

These included participants with congenital and with acquired sight loss. All<br />

participants from each sub-sample were recruited to meet different age band targets<br />

(see Table 3.1).<br />

22

3. Methodology<br />

Table 3.1 DAB radio consumer research sampling<br />

Age<br />

Sub-sample 18-30 years 31-64 years 65-74 years 75+ years<br />

Blind/partially sighted: mild 2 2 2 2<br />

Blind/partially sighted:<br />

moderate<br />

2 2 2 2<br />

Blind/partially sighted:<br />

severe<br />

Dyslexia 2 1<br />

2 2 2 2<br />

Dexterity 1 2<br />

Sighted controls 2 2 2 2<br />

3.1.2.1. Blind or partially sighted participants<br />

Twenty-four people (13 males, 11 females) who are blind or partially sighted were<br />

interviewed. Six were aged 18-30 years (4 males, 2 females), six were aged<br />

31-64 years (3 males, 3 females), six were aged 65-74 years (2 males, 4 females) and<br />

six were aged 75 years or older (2 females, 4 males). The sample was intentionally<br />

skewed towards older people to be broadly representative of the blind and partially<br />

sighted population, consistent with the age profile reported in the Network 1000<br />

report (Douglas, Corcoran, and Pavey, 2006) report (see section 3.2.2). Some of those<br />

in the oldest age brackets also reported being affected, to varying degrees, by<br />

dexterity and hearing problems.<br />

Sight loss and impact on everyday life<br />

In the blind and partially sighted sample, participants’ level of sight loss was<br />

categorised as mild, moderate or severe. This categorisation was as used in the<br />

Network 1000 research report (Douglas, Corcoran and Pavey, 2006). Prospective<br />

participants were asked to self-report how much, if any, vision they had using the<br />

same question presented by Douglas, Corcoran and Pavey (2006). The question is<br />

included in Appendix A of this report (question 25 of the project’s Short Preference<br />

Survey). Visual acuity was not tested during the course of this study. Information on<br />

their eye condition was provided by some participants – they were not routinely asked<br />

for this information, but were prompted to talk about their sight loss and, importantly,<br />

the impact on their lives. The participants had a wide range of eye conditions; those<br />

that were reported included macular degeneration, retinitis pigmentosa, coloboma,<br />

23

3. Methodology<br />

glaucoma, congenital cataracts, haemorrhage, and optic nerve hyperplasia. Some had<br />

no light perception whilst others had partial sight loss, and others had sight in only<br />

one eye. Those with some vision used high power magnifiers to aid their poor vision as<br />

well as a variety of assistive technologies to render day-to-day activities, technology<br />

and media accessible to them.<br />

“My vision is like a painting of Jack Vettriano” [meaning that she can see the<br />

general shapes of people, but not the details of their faces - almost like a<br />

silhouette.] [blind and partially sighted: mild sight loss, female, 65-74 years]<br />

“I can see your shape, your hair length, the colour of your dress but not the style of<br />

it or the details of your face. I use my vision as much as I possibly can.” [blind and<br />

partially sighted: moderate sight loss, female, 65-74 years]<br />

“I can see the outline of people; I see fuzzy, blur. I can see colours.”<br />

[blind and partially sighted: moderate sight loss, male, 75+ years]<br />

“I can see you but I can’t see your face. With my magnifier machine I can read, but<br />

just some words or the newspaper’s headline.”<br />

[blind and partially sighted: moderate sight loss, male, 75+ years]<br />

Occupational backgrounds<br />

Consistent with the Network 1000 report (Douglas, Corcoran & Pavey, 2006), the blind<br />

and partially sighted participants in the current study came from a wide range of<br />

occupational backgrounds. Occupations, both current and pre-retirement included civil<br />

servant, radio producer, nurse, recruitment consultant, florist, barman, factory worker,<br />

solicitor and judge, and physiotherapist. Some were studying for degrees. Given the<br />

recruitment skew towards participants aged between 65 and 74 years, and aged 75<br />

years and older, the current study’s qualitative sample was broadly consistent with<br />

Network 1000 figures on working status. It reported that 80 per cent of blind and<br />

partially sighted people described themselves as retired from paid work. Of the<br />

20 per cent of blind and partially sighted participants who had not yet retired, less<br />

than 35 per cent reported their employment status as employed (including those in<br />

paid employment, those reporting they were students, and those reporting they were<br />

self employed).<br />

Interests<br />

Interests were wide and diverse and included crafts, technology, walking, dancing,<br />

cookery, gardening, watching and/or playing sports (eg swimming or football),<br />

socialising, games/puzzles (eg crosswords, bridge or chess), music (eg playing piano,<br />

church bell ringing or attending concerts), theatre, reading books. Radio was enjoyed<br />

by all, as the participants were recruited as DAB radio users. Some participants were<br />

24

3. Methodology<br />

volunteering for their local church or for organisations aimed at supporting people with<br />

disabilities. As reported in Chapter 1, radio is generally a favoured pastime for blind<br />

and partially sighted people, so the sample’s interest in radio is representative.<br />

Living situations and whether help is available<br />

A range of living situations were sampled: some participants were married with children<br />

or lived just with their partner; others were living alone or in multi-share<br />

accommodation (students, supported housing for older people).<br />

3.1.2.2. Participants with dyslexia<br />

Three people with dyslexia were interviewed to explore any possible overlaps in<br />

accessibility/usability issues in DAB radio design. The participants with dyslexia were<br />

aged 24, 25 and 56 years.<br />

Dyslexia and impact on everyday life<br />

There was little evidence of a sense of exclusion due to dyslexia, particularly for the<br />

younger participants who felt that people were generally better informed about it<br />

today. The main impacts that they cited of dyslexia on their lives were in their<br />

schooling and in learning how to use new technologies.<br />

“..[dyslexia] is annoying and frustrating sometimes especially in terms of writing.<br />

[…] I don’t feel really excluded from things in society. Maybe I’d just like people<br />

to know more about dyslexia.” [Dyslexia, male, 18-30 years]<br />

“It was hard in school. Now it is better but sometimes I still find it difficult using<br />

the computer or reading or writing quickly. I don’t feel limited. People probably<br />

know about dyslexia more now than when I was 14.” [Dyslexia, male, 18-30 years]<br />

“I can’t read quickly; I need to read every word well - I can’t skim. I have to learn<br />

the shape of the words. I can’t understand grammar. I think my sense of exclusion<br />

is often linked to technology. It is difficult for me learning to use something<br />

without having someone to show me what to do. I need to visualise and<br />

experience.” [Dyslexia, female, 31-64 years]<br />

Occupational backgrounds<br />

Their occupations were dancer, health care assistant and a civil servant working in<br />

education.<br />

Interests<br />

Interests included walking, attending galleries, socialising, technology, gardening,<br />

music (playing an instrument and listening to), watching films, reading and listening<br />

to radio.<br />

25

3. Methodology<br />

Living situations and whether help is available<br />

One lived at home with his parents, another was a single parent, and the other lived in<br />

a shared household.<br />

3.1.2.3. Participants with manual dexterity impairment<br />

Three people with manual dexterity impairment were interviewed to explore any<br />

possible overlaps in accessibility/usability issues in DAB radio design. All three people<br />

suffered with arthritis and were aged between 65 and 83 years.<br />

Manual dexterity and impact on everyday life<br />

These participants had arthritis that was not just limited to the hands. This resulted in<br />

additional impairment in other areas of their life such as general mobility. Pain was<br />

commonly experienced and they had ‘good’ and ‘bad’ days with this. None felt<br />

excluded from society because of their impairment. Impacts were mostly noted in<br />

handling/grabbing heavy objects (eg cooking pans) and opening bottles and jars.<br />

Some people used specially designed products, such as jar openers.<br />

“During the last 6 years I have had to change part of my lifestyle. I don’t cook<br />

anymore because it’s difficult to grab things for me. The pain is not the same every<br />

day; sometimes it is better than others.” [Dexterity, female, 75+ years]<br />

“I have suffered from arthritis for many years but now it is getting worse. I have it<br />

in my hands, back and legs. I can do most of my day-to-day work. Opening bottles<br />

or jars is difficult but I have tools that help me. I also broke my shoulder a few<br />

years ago. I don’t consider myself disabled.” [Dexterity, female, 75+ years]<br />

“I don’t go out as much as I used to. I have had arthritis for six to seven years.<br />

Sometimes it’s really painful, other times it’s fine. I consider myself disabled and I<br />

am registered disabled as well. I don’t feel excluded at all.” [Dexterity, female, 60-<br />

74 years]<br />

Occupational backgrounds<br />

All three were over 65 and retired.<br />

Interests<br />

Interests included listening to the radio, cooking, socialising, watching TV, watching<br />

bowls and travelling.<br />

Living situations and whether help is available<br />

Two of the three participants were living alone, although one of these had relatives<br />

living close by who provided assistance when needed. The third participant with<br />

manual dexterity impairment was living with her partner.<br />

26

3. Methodology<br />

Participants with no reported sight loss, dyslexia, or manual dexterity impairment<br />

(‘sighted controls’).<br />

3.1.2.4. Participants with no reported sight loss, dyslexia or manual<br />

dexterity impairment (sighted controls)<br />

Occupational backgrounds<br />

The eight controls came from a range of backgrounds. Occupations included IT worker,<br />

teacher, receptionist, administrator and counsellor. Two were retired, and one was<br />

unemployed. One retired woman did voluntary work.<br />

Interests<br />

Interests included gardening, decorating, socialising, family activities, technology (eg<br />

computer/internet), keeping fit, cinema and film, TV, listening to the radio, shopping,<br />

writing stories, cooking, crafts (eg painting), and games (eg board and computer).<br />

Living situations and whether help is available<br />

A range of living situations was sampled (living alone, living with parents, and living<br />

with partner. Some had children who had left home.<br />

3.1.3. Procedure<br />

Participants were recruited across the UK by a range of methods including adverts in<br />

<strong>RNIB</strong> publications and press releases, other charities for blind people, partially sighted<br />

and older people, snowballing via existing participants, and through recruitment<br />

agencies. The interviewees lived in central and Greater London, Berkshire,<br />

Hertfordshire, Greater Manchester, Merseyside, East and West Midlands and Surrey.<br />

Each interviewee gave informed consent to take part and to be audio and video<br />

recorded for transcription purposes. The interview lasted between 45 minutes and 150<br />

minutes depending on how engaged participants were with the topic. The majority<br />

lasted approximately 90 minutes.<br />

The interview followed a semi-structured discussion guide that focused on the<br />

following areas:<br />

life situation<br />

hobbies, things interviewees like doing<br />

value of radio (ie frequency of use, preferences)<br />

radio equipment in household<br />

perceptions and expectations of DAB radio<br />

27

3. Methodology<br />

overview of uses of their own DAB radio<br />

adopting and using their own DAB radio<br />

demonstration of how interviewees use their DAB radios<br />

trying an unfamiliar DAB radio and expressing their thoughts (eg likes, dislikes,<br />

what’s easy and intuitive and what’s not) whilst using it.<br />

They used either:<br />

low-cost DAB radio ( around £25)<br />

DAB radio with voice output (around £100)<br />

DAB radio with advanced functions (around £200).<br />

At the end of the interview, participants were fully debriefed about the research<br />

objectives and each person was paid £30 for their time.<br />

The DAB radio consumer in-depth interview data (interview transcriptions and<br />

observations of DAB radio use noted by the interviewers) were used to generate a<br />

checklist for recommended features of DAB radio equipment. They also informed the<br />

development of a second phase in the consumer research - the Short Preference<br />

Survey (see below).<br />

3.2. Consumer research: Short Preference Survey<br />

3.2.1. Rationale<br />

In addition to revealing key usability and accessibility considerations for digital radio<br />

equipment design, the in-depth interviews identified the typical range of radio<br />

functions that participants used and understood, and those which were not used or<br />

understood. These insights informed the development of a 27-item telephone survey<br />

(the ‘Short Preference Survey’). Whilst the in-depth interviews provided rich contextual<br />

information about digital radio use, the aim of the Short Preference Survey was to<br />

collect quantitative data. A key focus was to understand the proportions of sighted<br />

and blind and partially sighted samples who could use their radios independently.<br />

3.2.2. Sample for the Short Preference Survey<br />

The target was to have a nationally representative sample of DAB radio users and a<br />

sample of 100 blind and partially sighted people, matched as closely as possible to the<br />

age profile of the nationally representative sample of DAB radio users.<br />

28

3. Methodology<br />

Data from the nationally representative sample was collected via the market research<br />

agency GfK NOP’s Telephone Omnibus. The Omnibus is a nationally representative<br />

telephone survey, conducted weekly with a target of 1,000 people per week to which<br />

additional sections or questions can be added to explore specific topics. The survey<br />

was conducted over the weekend of 9-11 May 2008. A total of 225 people from the<br />

national survey had DAB radio and were therefore asked the Short Preference Survey<br />

questions. Fifty-four per cent of the 225 DAB owners was male.<br />

As can be seen in Figure 3.1 (also see Results table [AB3.1] in Appendix B), and<br />

consistent with recent Digital Radio Development Bureau data (2007), DAB owners<br />

tend to be over-represented in the middle age groups (31-64 years old), and underrepresented<br />

in older age groups.<br />

Table 3.1 Comparison of the age distribution of the research sub-samples with<br />

the Network 1000 nationally representative data for the blind and partially<br />

sighted population<br />

50%<br />

45%<br />

40%<br />

35%<br />

30%<br />

25%<br />

20%<br />

15%<br />

10%<br />

5%<br />

0%<br />

18–29 30–49 50–64 65+<br />

age group (years)<br />

nationally representative (all) (n=999)<br />

nationally representative DAB (n=225)<br />

blind and partially sighted DAB (n=100)<br />

Network 1000 (comparison: n=100)<br />

29

3. Methodology<br />

Data collection for the Short Preference Survey with the blind and partially sighted<br />

sample took place between 13 June and 7 August 2008. In contrast to the nationally<br />

representative sample which was recruited with cold calling, all participants for the<br />

blind and partially sighted sample had volunteered to participate in response to adverts<br />

and via word of mouth. The adverts specified that only people using DAB radios should<br />

respond. Efforts were made in recruitment of the DAB sample to broadly match the<br />

nationally representative DAB sample in terms of age. However, as shown by the<br />

Network 1000 data (Douglas et al. (2006)) shown in Figure 3.1 above (also see Results<br />

table [AB3.1] in Appendix B), the age profile of blind and partially sighted people in<br />

the UK is very heavily skewed towards older age. To make sure the survey captured<br />

meaningful data about the experiences of DAB from blind and partially sighted people,<br />

efforts were also made to recruit a slightly older sample of blind and partially sighted<br />

DAB users. It is important to note that whilst older blind and partially sighted people<br />

are therefore somewhat under-represented in the survey, this is likely to be a fairly<br />

accurate estimate of the age profile of blind and partially sighted DAB listeners -<br />

showing the same tail off in DAB ownership for older participants as is apparent in the<br />

sighted nationally representative sample.<br />

Respondents in the blind and partially sighted sample were recruited via similar<br />

methods as participants for the in depth interviews. Sixty-nine per cent of the blind<br />

and partially sighted sample were male. Whilst this skew differs from the general<br />

population profile of blind and partially sighted people, it is consistent with the male<br />

skew in DAB ownership in the nationally representative sample. It is also possible that<br />

male DAB owners were more likely than female DAB owners to volunteer to participate<br />

in a survey on DAB. Reasons for this may include: that more males were invited to<br />

participate (eg recruitment methods targeted more men than women), or that males<br />

are more confident than females in talking about media technology.<br />

The age profile of the two samples is shown in Table 3.2 right.<br />

30

3. Methodology<br />

Table 3.2. Short Preference Survey: age profile of the samples of DAB owners<br />

(unweighted)<br />

Age band<br />

Nationally representative<br />

sample (n=225)<br />

Blind and partially<br />

sighted sample (n=100)<br />

18-24 years 12% 2%<br />

25-34 years 14.2% 10%<br />

35-44 years 18.2% 18%<br />

45-54 years 21.8% 25%<br />

55-64 years 19.6% 24%<br />

65-74 years 9.8% 11%<br />

75-84 years 4.0% 5%<br />

85+ years 0.4% 5%<br />

TOTAL 100% 100%<br />

3.2.3. Procedure<br />

The Short Preference Survey asked respondents to focus on one DAB radio that they<br />

used the most, and probed their first experiences of having used that DAB radio and<br />

then their subsequent day to day across a range of different functions (See Appendix A<br />

for the full survey).<br />

They were asked if they needed any advice, help or support from any other person<br />

with a range of potential actions/functions that they have explored using their radio.<br />

For ease of analysis, there were three response options:<br />

1. yes, needed help from someone<br />

2. no, could do independently<br />

3. don’t know/not applicable - didn’t use/radio doesn’t offer that function.<br />

31

3. Methodology<br />

There were 19 tasks specified, for which respondents were asked to report on their<br />

experience of first-time use of the DAB radio they used the most:<br />

a. getting the radio out of its packaging<br />

b. using the operating instructions that came with it<br />

c. plugging the radio in<br />

d. inserting batteries<br />

e. switching the radio on/off<br />

f. tuning the radio in (scanning for channels)<br />

g. setting/storing presets<br />

h. accessing information on the text display<br />

i. knowing which station they were listening to<br />

j. changing station<br />

k. tuning to a specific station (eg BBC Radio 4)<br />

l. changing volume<br />

m. using a remote control to control your digital radio<br />

n. finding out what programmes were going to be on later that evening or that week,<br />

using the radio to do this<br />

o. finding out what the time was using the radio<br />

p. pausing live radio<br />

q. forwarding and/or rewinding back to live radio<br />

r. recording a radio programme<br />

s. playing back a recorded programme<br />

There were 18 tasks for which the respondents were asked to report on their<br />

experience of subsequent use of this same digital radio, which were very similar to the<br />

tasks specified above with some changes:<br />

a. using the operating instructions<br />

b. plugging the radio in<br />

c. changing batteries<br />

32

3. Methodology<br />

d. switching the radio on/off<br />

e. retuning the radio (re-scanning to find new stations)<br />

f. updating/re-setting/re-storing presets<br />

g. accessing information on the text displays<br />

h. knowing which station they are listening to<br />

i. changing station<br />

j. tuning to a specific station (eg BBC Radio 4)<br />

k. changing volume<br />

l. using a remote control to control your digital radio<br />

m. finding out what programmes were going to be on later that evening or that week,<br />

using the radio to do this<br />

n. finding out what the time was using the radio<br />

o. pausing live radio<br />

p. forwarding and/or rewinding back to live radio<br />

q. recording a radio programme<br />

r. playing back a recorded programme<br />

The survey also probed what features participants thought their radio supported and<br />

asked participants to nominate up to five features that they thought were most useful<br />

to have on a DAB radio. They were asked about any difficulties they experienced using<br />

their DAB radio, how they remedied problems and to what extent they felt the DAB<br />

radio they were assessing for the survey was easy to use.<br />

Other more general questions asked participants about their DAB radio listening<br />

patterns and favourite station genres and stations. Finally, participants were asked a<br />

series of demographic questions, and the blind and partially sighted respondents were<br />

asked about their level of vision.<br />

The survey took 15 - 45 minutes to complete with each person. Most surveys took<br />

20.–25 minutes. There was no financial incentive to take part.<br />

33

3. Methodology<br />

3.2.4. Methodology for assessing impact of voice output<br />

A subset of the items relating to ‘basic use’ are explored separately to full, complete<br />

use (all items). Items 1. to 12. from the ‘first time use’ list were considered related to<br />

basic, core use. Items 1 to 11 from the ‘subsequent use’ list were considered related to<br />

basic, core use.<br />

The data were explored in different ways:<br />

Proportion of sample reporting ‘yes, needed help’ for any of the ‘basic’ tasks (a<br />

crude index of basic tasks relate to items 1 to 12 for first time use, and 20 to 38 for<br />

subsequent use).<br />

Proportion of sample reporting ‘yes, needed help’ to any of the ‘first use’ tasks (12<br />

items.<br />

Proportion of sample reporting ‘yes, needed help’ to any of the ‘subsequent use’<br />

tasks (11 items)<br />

Proportion of sample reporting ‘yes, needed help’ for any of the tasks<br />

Proportion of sample reporting ‘yes, needed help’ to any of the ‘first time use’ tasks<br />

(19 items)<br />

Proportion of sample reporting ‘yes, needed help’ to any of the ‘subsequent use’<br />

tasks (18 items)<br />

Average number of tasks/items for which the samples needed help from someone<br />

else (for all tasks and basic tasks as defined above)<br />

3.3. Industry research: semi-structured interviews<br />

3.3.1. Rationale<br />

The industry research was conducted to address research questions 4 and 5, about how<br />

and whether accessibility features in product design and what barriers industry cites for<br />

developing accessible digital radio equipment.<br />

3.3.2. Sample<br />

Six semi-structured interviews were conducted with senior staff members (eg Chief<br />

Executives, Chief Operating Officers, Directors/Senior Management) across different<br />

parts of the consumer digital radio equipment supply chain. Five manufacturers and<br />

one component supplier participated. Some retailers were also invited to participate,<br />

34

3. Methodology<br />

though none accepted the invitation. The interviews were conducted face-to-face<br />