Volume 35 June 2009 Number 1 - University of Mosul

Volume 35 June 2009 Number 1 - University of Mosul

Volume 35 June 2009 Number 1 - University of Mosul

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Annals <strong>of</strong><br />

the College<br />

<strong>of</strong> Medicine<br />

<strong>Mosul</strong><br />

<strong>Volume</strong> <strong>35</strong> <strong>June</strong> <strong>2009</strong> <strong>Number</strong> 1<br />

Editorial Board<br />

Taher Q. AL‐DABBAGH<br />

Hisham A. Al‐ATRAKCHI<br />

Budoor A. K. AL‐IRHAYIM<br />

Kahtan B. IBRAHEEM<br />

Ilham K. AL‐JAMMAS<br />

Sahar K. OMAR<br />

Rami M. AL‐HAYALI<br />

Editor<br />

Deputy Editor<br />

Member<br />

Member<br />

Member<br />

Member<br />

Member & Manager<br />

Faiza A. ABDULRAHMAN<br />

Administration<br />

A publication <strong>of</strong> the College <strong>of</strong> Medicine, <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Mosul</strong>, <strong>Mosul</strong>, Iraq

Annals <strong>of</strong><br />

the College<br />

<strong>of</strong> Medicine<br />

<strong>Mosul</strong><br />

(Ann Coll Med <strong>Mosul</strong>)<br />

Instructions to Authors<br />

Annals <strong>of</strong> the College <strong>of</strong> Medicine <strong>Mosul</strong> is published biannually and accepts review articles,<br />

papers on laboratory, clinical, and health system researches, preliminary communications,<br />

clinical case reports, and letters to the Editor, both in Arabic and English. Submitted material<br />

is received for evaluation and editing on the understanding that it has neither been published<br />

previously, nor will it, if accepted, be submitted for publication elsewhere.<br />

Manuscripts, including tables, or illustrations are to be submitted in triplicate with a covering<br />

letter signed by all authors, to the Editorial Office, Annals <strong>of</strong> the College <strong>of</strong> Medicine <strong>Mosul</strong>,<br />

Iraq. All the submitted material should be type written on good quality paper with double<br />

spacing and adequate margins on the sides. Rigorous adherence to the "Uniform<br />

Requirements for Manuscripts Submitted to Biomedical Journals" published by the<br />

International Committee <strong>of</strong> Medical Journals Editors in 1979 and revised in1981 should be<br />

observed. Also studying the format <strong>of</strong> papers published in a previous issue <strong>of</strong> the Annals is<br />

strongly advised (Ann Coll Med <strong>Mosul</strong> 1988; 14:91-103).<br />

Each part <strong>of</strong> the manuscript should begin in a new page, in the following order: title; abstract;<br />

actual text usually comprising a short relevant introduction, materials and methods or patients<br />

and methods, results, discussion; acknowledgement; references; tables; legends for<br />

illustrations. <strong>Number</strong> all pages consecutively on the top <strong>of</strong> right corner <strong>of</strong> each page, starting<br />

with title page as page 1. The title page should contain (1) the title <strong>of</strong> the paper; (2) first name,<br />

middle initial(s) and last name <strong>of</strong> each author; (3) name(s) and address(es) <strong>of</strong> institution(s) to<br />

which the work should be attributed. If one or more <strong>of</strong> the authors have changed their<br />

addresses, this should appear as foot notes with asterisks; (4) name and address <strong>of</strong> author to<br />

whom correspondence and reprint request should be addressed (if there are more than one<br />

author);(5) a short running head title <strong>of</strong> no more than 40 letters and spaces.<br />

The second page should contain (1) title <strong>of</strong> the paper (but not the names and addresses <strong>of</strong><br />

the authors); (2) a self contained and clear structured abstract representing all parts <strong>of</strong> the<br />

paper in no more than 200 words in Arabic and in English. The headings <strong>of</strong> the abstract<br />

include: objective, methods, results, and conclusion.<br />

References should be numbered consecutively both in the text and in the list <strong>of</strong> references, in<br />

the order in which they appear in the text. The punctuation <strong>of</strong> the Vancouver style should be<br />

followed strictly in compiling the list <strong>of</strong> references. The following are two examples (1) for<br />

periodicals: Leventhal H, Glynn K, Fleming R. Is smoking cessation an "informed choice"?<br />

Effect <strong>of</strong> smoking risk factors on smoking beliefs. JAMA 1987; 257:3373-6. (2) For books:<br />

Cline MJ, Haskell CM. Cancer chemotherapy. 3 rd ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1980:309-<br />

30. If the original reference is not verified by the author, it should be given in the list <strong>of</strong><br />

references followed by "cited by…" and the paper in which it was referred to.<br />

The final version <strong>of</strong> an accepted article has to be printed, including tables, figures, and<br />

legends on CD, and presented as they are required to appear in the Annals. Three<br />

dimensional drawings <strong>of</strong> figures must be avoided.<br />

ISSN 0027-1446<br />

CODE N: ACCMMIB<br />

E-mail: annalsmosul@yahoo.com

Annals <strong>of</strong><br />

the College<br />

<strong>of</strong> Medicine<br />

<strong>Mosul</strong><br />

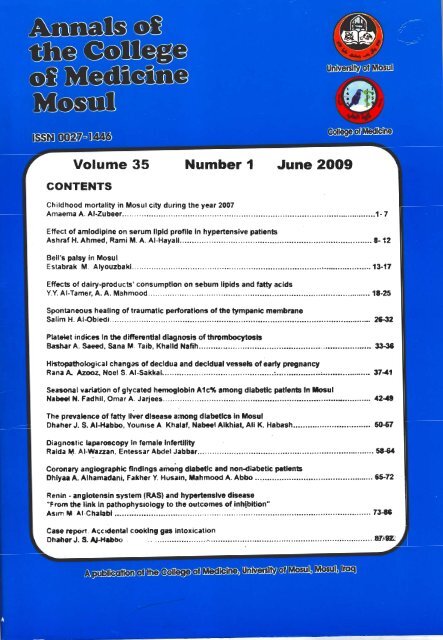

CONTENTS<br />

<strong>Volume</strong> <strong>35</strong> <strong>Number</strong> 1 <strong>June</strong> <strong>2009</strong><br />

Childhood mortality in <strong>Mosul</strong> city during the year 2007<br />

Amaema A. Al-Zubeer………………………………………………………………………………...………1- 7<br />

Effect <strong>of</strong> amlodipine on serum lipid pr<strong>of</strong>ile in hypertensive patients<br />

Ashraf H. Ahmed, Rami M. A. Al-Hayali………………………………………………………………….… 8- 12<br />

Bell’s palsy in <strong>Mosul</strong><br />

Estabrak M. Alyouzbaki………………………………………………………………………...….……….. 13-17<br />

Effects <strong>of</strong> dairy-products' consumption on sebum lipids and fatty acids<br />

Y.Y. Al-Tamer, A. A. Mahmood…………………………………………………………………………...… 18-25<br />

Spontaneous healing <strong>of</strong> traumatic perforations <strong>of</strong> the tympanic membrane<br />

Salim H. Al-Obiedi………………………………………………………………………………………..…... 26-32<br />

Platelet indices in the differential diagnosis <strong>of</strong> thrombocytosis<br />

Bashar A. Saeed, Sana M. Taib, Khalid Nafih………………………………………………………….…. 33-36<br />

Histopathological changes <strong>of</strong> decidua and decidual vessels <strong>of</strong> early pregnancy<br />

Rana A. Azooz, Noel S. Al-Sakkal……………………………………………………………………....…. 37-41<br />

Seasonal variation <strong>of</strong> glycated hemoglobin A 1c % among diabetic patients in <strong>Mosul</strong><br />

Nabeel N. Fadhil, Omar A. Jarjees………………………………………………………………..…….….. 42-49<br />

The prevalence <strong>of</strong> fatty liver disease among diabetics in <strong>Mosul</strong><br />

Dhaher J. S. Al-Habbo, Younise A. Khalaf, Nabeel Alkhiat, Ali K. Habash……….……………….…… 50-57<br />

Diagnostic laparoscopy in female infertility<br />

Raida M. Al-Wazzan, Entessar Abdel Jabbar………………………………………………………...….… 58-64<br />

Coronary angiographic findings among diabetic and non-diabetic patients<br />

Dhiyaa A. Alhamadani, Fakher Y. Husain, Mahmood A. Abbo ………………………………………..… 65-72<br />

Renin – angiotensin system (RAS) and hypertensive disease<br />

"From the link in pathophysiology to the outcomes <strong>of</strong> inhibition"<br />

Asim M. Al-Chalabi …………………………………………………………….………….………….….…… 73-86<br />

Case report: Accidental cooking gas intoxication<br />

Dhaher J. S. Al-Habbo…………………………………………………………………….………….….…… 87-92<br />

Printing <strong>of</strong> this issue was completed on Mar, 2010.

Annals <strong>of</strong> the College <strong>of</strong> Medicine Vol. <strong>35</strong> No. 1, <strong>2009</strong><br />

Childhood mortality in <strong>Mosul</strong> city during the year 2007<br />

Amaema A. Al-Zubeer<br />

Department <strong>of</strong> Community Medicine, College <strong>of</strong> Medicine, <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Mosul</strong>.<br />

(Ann. Coll. Med. <strong>Mosul</strong> <strong>2009</strong>; <strong>35</strong>(1): 1-7).<br />

Received: 20 th May 2008; Accepted: 24 th Sept 2008.<br />

ABSTRACT<br />

Objectives: To calculate infant and under five mortality rates and to find out the most common<br />

causes <strong>of</strong> death among children.<br />

Methods:<br />

Study period: The study was done over a period <strong>of</strong> one month, during Dec. 2007.<br />

Study design: Rapid epidemiological survey using UNICEF “last birth technique”.<br />

Study setting: The study was done at Al-Hadbaa Primary Health Care Center in <strong>Mosul</strong> city.<br />

Study population: Data was collected from 1046 mothers in child bearing age (15-49 years), who were<br />

attending at the antenatal clinic by direct interviewing using a questionnaire form based on the model<br />

formulated by UNICIF for childhood mortality survey.<br />

Results: The present study showed that the estimated under five mortality rate is 107 /1000 <strong>of</strong> last<br />

live births which represents a rise <strong>of</strong> 2.5 fold since WHO Maternal and Child Mortality Survey was<br />

done at 1990 in Iraq. The Infant mortality rate was estimated to be 95.6 death / 1000 <strong>of</strong> last live births.<br />

The study also showed that the neonatal mortality (0-28 days) constitutes 40.9/1000 last live birth<br />

which accounts for 42% from all deaths that occur during 1 st year <strong>of</strong> life. Other findings showed that<br />

more than a quarter <strong>of</strong> all causes <strong>of</strong> deaths among under five were related to respiratory problems<br />

and 15.5% <strong>of</strong> all causes were linked to congenital abnormalities. Diarrheal disease accounted for<br />

8.6% <strong>of</strong> causes.<br />

Conclusion: Results showed that under five mortality is still considered a major health problem and<br />

reflecting defect in health system <strong>of</strong> the community, needs to be re-evaluated and minimized to be as<br />

least as possible.<br />

الخلاصة<br />

أهداف البحث: لحساب وفيات الأطفال دون السنة ودون الخامسة من العمر في مدينة الموصل ولاآتشاف سبب الوفاة<br />

الأآثر شيوعا بين الأطفال.<br />

طريقة إجراء البحث: تم إجراء مسح وبائي سريع باستخدام حساب تقنية الولادة الأخيرة التابع لليونيسيف في مرآز الحدباء<br />

أماً تتراوح<br />

جمعت العينات من للرعاية الصحية الأولية في مدينة الموصل خلال مدة شهر في آانون الثاني من النساء اللواتي يراجعن عيادة رعاية الحوامل بواسطة المقابلة المباشرة مستخدمين استمارة<br />

أعمارهن من استبيان معتمدة على موديل مصاغ من اليونيسيف لمسح وفيات الأطفال.<br />

أخر ولادة<br />

وفاة لكل النتائج: أظهرت الدراسة الحالية أن المعدل المحسوب لوفيات الأطفال دون الخامسة هو حية والتي تمثل ارتفاع بمقدار مرتين ونصف منذ مسح منظمة الصحة العالمية لوفيات الأمومة والطفولة الذي تم في<br />

أخر ولادة حية.<br />

وفاة لكل في العراق. أن المعدل المحسوب لوفيات الرضع دون السنة من العمر هو من آل<br />

أخر ولادة حية والتي تمثل لكل يوم) تشكل آما وأظهرت الدراسة أن وفيات الخدج الوفيات الحاصلة خلال السنة الأولى من الحياة. نتائج أخرى أظهرت أنه أآثر من ربع أسباب وفيات الأطفال دون الخامسة<br />

%٤٢<br />

١٠٤٦<br />

١٠٠٠<br />

١٠٠٠<br />

١٠٧<br />

٩٥,٦<br />

.٢٠٠٧<br />

١٠٠٠<br />

٤٠,٩<br />

٢٨ -٠)<br />

،(٤٩-١٥)<br />

١٩٩٠<br />

© <strong>2009</strong> <strong>Mosul</strong> College <strong>of</strong> Medicine 1

Annals <strong>of</strong> the College <strong>of</strong> Medicine Vol. <strong>35</strong> No. 1, <strong>2009</strong><br />

من آل<br />

من آل الأسباب مرتبطة بتشوهات خلقية بينما يشكل الإسهال لها علاقة بالمشاآل التنفسية و الأسباب.<br />

الاستنتاج: أظهرت النتائج أن وفيات الأطفال دون الخامسة من العمر ما تزال تعتبر مشكلة صحية مهمة وتعكس الخلل في<br />

النظام الصحي للمجتمع، و تحتاج إلى تقييم و تحسين.<br />

% ٨,٦<br />

%١٥,٥<br />

C<br />

hildren are the future <strong>of</strong> society and their<br />

mothers are guardians <strong>of</strong> that future (1) .<br />

Pregnancy, child birth and their consequences<br />

are still the leading causes <strong>of</strong> death, disease<br />

and disability among women <strong>of</strong> reproductive<br />

age in developing countries<br />

(2) . Childhood<br />

mortality which comprises infant mortality rate<br />

and under five mortality rate are key indicators<br />

used internationally, nationally and locally as a<br />

sensitive but not specific way <strong>of</strong> comparing<br />

health status and development within<br />

countries (3) . Under five mortality rate is also a<br />

good reflection <strong>of</strong> the general wellbeing <strong>of</strong><br />

children in an area (4, 5) . Across the world there<br />

is an overall downward trend in under five<br />

mortality rates (6, 7) . However, this trend was<br />

showing sign <strong>of</strong> slowing lately, though till the<br />

year 2005, almost 11 million children under<br />

five years <strong>of</strong> age died from causes that are<br />

largely preventable globally. Among them are<br />

4 million who will not survive the first month <strong>of</strong><br />

life<br />

(1,8) . Poor or delayed care-seeking<br />

contributes up to 70% <strong>of</strong> child death. More<br />

than 50% <strong>of</strong> all child deaths globally occur in<br />

just six counties: China, the Democratic<br />

Republic <strong>of</strong> Congo, Ethiopia, India and<br />

Pakistan (8) . There are several factors<br />

contributing to the death <strong>of</strong> infants and<br />

children (9) , these include socio-demographic<br />

status <strong>of</strong> family, level <strong>of</strong> community<br />

development and education, (availability,<br />

access and quality <strong>of</strong> health services) with<br />

neonatal mortality is associated with maternal<br />

health and access to care around the time <strong>of</strong><br />

delivery and the presence <strong>of</strong> preventive and<br />

curative health services (10,11) which in fact are<br />

still poor in Iraq.<br />

The aim <strong>of</strong> the present study is to determine<br />

the under five mortality in the catchment area<br />

<strong>of</strong> Al- Hadbaa Primary Health Care Center in<br />

<strong>Mosul</strong> city during the year 2007 using rapid<br />

epidemiological survey and to find out the<br />

most common causes <strong>of</strong> death among the<br />

study sample.<br />

Specific objective<br />

To estimate the under five mortality rate,<br />

infant mortality rate and neonatal mortality<br />

among the study sample.<br />

To find out the most common causes <strong>of</strong><br />

death among children under five years <strong>of</strong> age.<br />

To compare the estimated present under five<br />

mortality rates with previous rates that have<br />

been estimated in Iraq.<br />

Methods<br />

The survey was conducted at Al-Hadbaa<br />

Primary Health Care Center which represents<br />

one <strong>of</strong> the most crowded centers in <strong>Mosul</strong> city.<br />

The study sample included 1046 mothers in<br />

child bearing age (15-49 years) who attended<br />

at the antenatal clinic in the center which<br />

represent 87% <strong>of</strong> all mothers attending the<br />

center during one month period. This center<br />

has a catchment area <strong>of</strong> approximately 13000<br />

women in child bearing age and 11500<br />

children under five years (12) . The study was<br />

conducted during Dec. 2007. A questionnaire<br />

form was prepared using “last birth technique”<br />

module formulated by UNICEF for childhood<br />

mortality survey in developing countries (11) .<br />

The questionnaire included information about<br />

mother’s age, previous deliveries and the outcome<br />

<strong>of</strong> each delivery, causes <strong>of</strong> death if<br />

present and age <strong>of</strong> child at death. It was<br />

reviewed with teaching staff <strong>of</strong> community<br />

department to assess its validity which was<br />

92%. Results approach was applied on it to<br />

measure the reliability <strong>of</strong> the answers, and it<br />

was correct in 81%. Filling up the<br />

questionnaire form was done by direct<br />

interview with the mothers at the antenatal<br />

clinic. The response rate was 97%. In addition<br />

to that, the investigator had visited the<br />

Statistical Unit in Nineveh Health Office and<br />

Al-Khannsa Hospital and the under five<br />

mortality rates were calculated from the<br />

registered deaths in the records <strong>of</strong> those units<br />

for comparison purposes.<br />

© <strong>2009</strong> <strong>Mosul</strong> College <strong>of</strong> Medicine 2

Annals <strong>of</strong> the College <strong>of</strong> Medicine Vol. <strong>35</strong> No. 1, <strong>2009</strong><br />

Age specific parity was calculated by dividing<br />

the number <strong>of</strong> children ever born in a specific<br />

age group over the total number <strong>of</strong> mothers in<br />

that age group. The under five mortality rates<br />

were calculated by dividing the total number <strong>of</strong><br />

children died below five years over the total<br />

number <strong>of</strong> last live birth multiplied by one<br />

thousand. Similar procedure was done to<br />

calculate the infant and neonatal mortality<br />

rates (13,14) .<br />

Data collection, computer feeding, tabulation<br />

and statistical analysis were conducted by the<br />

investigator herself using Minitab statistical<br />

s<strong>of</strong>tware version XIII. Chi square test was<br />

used and odds ratio for finding association.<br />

Results<br />

Table (1) shows that the overall estimated<br />

under five mortality rate is 107 / 1000 live<br />

births. From the analysis <strong>of</strong> data <strong>of</strong> the present<br />

study, the estimated infant mortality rate is<br />

95.6 deaths/1000 last live birth. Neonatal<br />

mortality (0-28 days) constitutes 40.9/1000 last<br />

live birth which account for 42% <strong>of</strong> all deaths<br />

that occur during 1 st year <strong>of</strong> life. The table also<br />

indicates that less than five mortality is higher<br />

among age group (45-49), as it reaches 208.5<br />

per 1000 live births.<br />

Table (2) represents the estimation <strong>of</strong> risk <strong>of</strong><br />

under five deaths among women age 45-49<br />

years in comparison with the other age groups.<br />

Children whose mothers’ age among the age<br />

range 45-49 year have significantly 2 fold risk<br />

<strong>of</strong> under five death than other children<br />

(OR=2.2, 95% CI= (1.510, 2.917), P value<br />

Annals <strong>of</strong> the College <strong>of</strong> Medicine Vol. <strong>35</strong> No. 1, <strong>2009</strong><br />

Table (3): Age distribution <strong>of</strong> women with their total children ever born and average parity<br />

No. <strong>of</strong> children ever born Average<br />

Mother’s age group All women<br />

parity<br />

Male Female Total /mother<br />

15- 48 32 24 56 1.16<br />

20- 298 315 289 604 2.02<br />

25- 228 279 319 598 2.62<br />

30- 140 255 281 536 3.82<br />

<strong>35</strong>- 176 469 4<strong>35</strong> 904 5.13<br />

40- 113 389 <strong>35</strong>5 744 6.58<br />

45-49 43 166 118 284 6.60<br />

Total 1046 1905 1821 3726 Sum<br />

Table (4): Distribution <strong>of</strong> death cases by causes and sex<br />

Causes Male Female Total Percent<br />

Respiratory* problem 59 36 95 26.38<br />

Congenital abnormality 27 29 56 15.55<br />

Fever* 22 27 49 13.6<br />

Premature 15 18 33 9.1<br />

Diarrhea* 15 16 31 8.6<br />

Unknown* 18 12 30 8.3<br />

Others** 36 30 66 18.3<br />

Totals 192 168 360 100%<br />

*These causes are classified under international classification <strong>of</strong> diseases 10 th revision (15,16,17) .<br />

**Others: Include injury, accidents, meningitis, septicemia.<br />

Discussion<br />

Childhood mortality rates are used to<br />

determine the level <strong>of</strong> human and economic<br />

development <strong>of</strong> the country (18,19) . The present<br />

survey indicates that under five mortality rates<br />

is 107/1000 last live birth which represents 2.5<br />

fold rise <strong>of</strong> under five mortality rates estimated<br />

by UNICIF/WHO maternal and child mortality<br />

survey done at 1990 which was 41/1000 live<br />

birth (20 ,21) . The results that were obtained from<br />

the vital registration system show that the<br />

estimated under five mortality for the year<br />

2007 is 24/1000 live birth and the infant<br />

mortality rate is 19.5/1000 live birth that occur<br />

during the year 2007. Another datum that has<br />

been taken from the Statistics Unit <strong>of</strong> Al-<br />

Khannsa Hospital shows more or less similar<br />

results as under five mortality rate was<br />

32/1000 live birth and the IMR was 28.58/1000<br />

live birth. These findings yield that only 20.4 %<br />

<strong>of</strong> all infant mortality which occurred has been<br />

registered and only 22.4 % <strong>of</strong> real under five<br />

mortality has been registered as compared<br />

with the present survey results (22) . Similarly,<br />

almost one third <strong>of</strong> deaths (29.8 %) has been<br />

registered in Al-Khannsa Hospital Statistical<br />

Unit for both infant and under five mortality<br />

when compared with the result <strong>of</strong> the present<br />

survey (23) . This is due to information on deaths<br />

from the health information system,<br />

unfortunately, does not reflect the mortality<br />

picture from population perspective because it<br />

is government facility – based data and thus<br />

does not include deaths that occur outside<br />

such facilities or from private heath institutions<br />

(24) . In many developing countries, vital<br />

registration data are incomplete. The severity<br />

<strong>of</strong> the under-reporting varies from country to<br />

country, and also varies over time within<br />

© <strong>2009</strong> <strong>Mosul</strong> College <strong>of</strong> Medicine 4

Annals <strong>of</strong> the College <strong>of</strong> Medicine Vol. <strong>35</strong> No. 1, <strong>2009</strong><br />

countries (25) . This under reporting <strong>of</strong> the<br />

registration system represents the top <strong>of</strong> the<br />

iceberg phenomena (14) . Birth history<br />

information from surveys provides the most<br />

robust estimation <strong>of</strong> infant and child mortality<br />

(12, 26) .<br />

A survey done at rural area near <strong>Mosul</strong><br />

during 1992 showed rise in under five mortality<br />

rates <strong>of</strong> 61 death /1000 live birth (28) . Another<br />

survey done at Al-Zangelle district in <strong>Mosul</strong><br />

city during the year 2002 showed that under<br />

five mortality rates was 166/1000 live birth (29) .<br />

The present study picture may reflect slight<br />

decline in childhood mortality since 2002 but it<br />

is still very high and unless progress is<br />

accelerated significantly, there is little hope <strong>of</strong><br />

reducing child mortality by two thirds by the<br />

target date <strong>of</strong> 2015 – the targets set by the<br />

millennium declaration (8) . Globally there is<br />

decline in the child mortality as mentioned by<br />

WHO (8) , while, the actual number <strong>of</strong> deaths is<br />

highest in Asia<br />

(30,31) , the rates for both<br />

neonatal deaths and still births are greatest in<br />

Sub Sahara Africa (27) . In addition to that, it<br />

was reported that there are some regions <strong>of</strong><br />

the world which underwent humanitarian crisis<br />

where mortality rates are “stagnating” and Iraq<br />

is one <strong>of</strong> these regions (8) . A study done during<br />

2004 for estimation <strong>of</strong> mortality before and<br />

after 2003 invasion <strong>of</strong> Iraq showed that the risk<br />

<strong>of</strong> death was estimated to be 2.5 higher after<br />

invasion when compared with pre invasion<br />

period (32) . The present study revealed that<br />

there is a steady increase in the average parity<br />

per mother with increase <strong>of</strong> age <strong>of</strong> mothers.<br />

This gives explanation <strong>of</strong> why mortality rate is<br />

still stagnating because modest reductions <strong>of</strong><br />

mortality rates are too small to keep up with<br />

the increasing numbers <strong>of</strong> births (8) .<br />

The present study also showed that the<br />

estimated infant mortality rate is 95.5 / 1000<br />

last live birth and neonatal mortality is 40/<br />

1000 last live birth. Thus the neonatal mortality<br />

constitutes 42% <strong>of</strong> all deaths that occur during<br />

1 st year <strong>of</strong> life. Across the world, newborn<br />

deaths contribute to about 40 % <strong>of</strong> all deaths<br />

in children under five years <strong>of</strong> age and more<br />

than half <strong>of</strong> infant mortality (8) . A survey done<br />

by UNICEF at early nineties showed that infant<br />

mortality rate was 32 per thousand live births<br />

during 1990 and increased afterwards to 93<br />

deaths per thousand live births 1994 (20) .<br />

Another result <strong>of</strong> the present study indicated<br />

that the most common cause <strong>of</strong> deaths among<br />

under five was respiratory problems as they<br />

constitute 26.3% <strong>of</strong> all causes, these problems<br />

occur most commonly within the 1 st year <strong>of</strong> life.<br />

Across the world, deaths among under five are<br />

still attributable to just handful <strong>of</strong> conditions<br />

that are avoidable through existing<br />

interventions<br />

(1) . These are acute lower<br />

respiratory infection mostly pneumonia (10%)<br />

<strong>of</strong> all death, diarrhea (15%), measles (4%),<br />

HIV/AIDS (3%), and neonatal conditions and<br />

mainly preterm birth, birth asphyxia and<br />

infections (37%) (8) . The present study also<br />

revealed that mortality among males is higher<br />

than females; this could be due to boys being<br />

more frail than girls. Many studies had<br />

confirmed this trend in mortality (19, 24) .<br />

Conclusions and recommendations<br />

There is high rate <strong>of</strong> childhood mortality<br />

recognized in <strong>Mosul</strong> city during the year 2007<br />

together with the presence <strong>of</strong> high fertility rate<br />

and so there is an urgent need for strategy for<br />

prevention <strong>of</strong> childhood mortality in Iraq<br />

through health services provision and<br />

socioeconomic development and improvement<br />

<strong>of</strong> family planning facilities.<br />

References<br />

1. World Health Organization. Monitoring the<br />

Situation <strong>of</strong> Children and Women:<br />

Findings from the Multiple Indicator<br />

Cluster Survey, UNICEF report, 2006.<br />

2. Rutstein SO. Factors associated with<br />

trends in infant and child mortality in<br />

developing countries during the 1990s.<br />

Bulletin <strong>of</strong> the World Health Organization<br />

2000; 78: 1256–70.<br />

3. Korenromp EL, Arnold F, Williams BG,<br />

Nahlen BL and Snow RW. Monitoring<br />

trends in under-5 mortality rates through<br />

national birth history surveys. International<br />

Journal <strong>of</strong> Epidemiology 2004; 33: 1293–<br />

1301.<br />

4. Dunkelberg E. Measuring Child Well-Being<br />

in the Mediterranean Countries —Toward<br />

a Comprehensive Child Welfare.<br />

Amsterdam Institute for International<br />

© <strong>2009</strong> <strong>Mosul</strong> College <strong>of</strong> Medicine 5

Annals <strong>of</strong> the College <strong>of</strong> Medicine Vol. <strong>35</strong> No. 1, <strong>2009</strong><br />

Development, Wagstaff and Watanabe<br />

(2000): p 23.<br />

5. Randall B, Wilson A. The 2006 annual<br />

report <strong>of</strong> the Regional Infant and Child<br />

Mortality Review Committee. S D Med<br />

2007; 60(9): 343, 345, 347.<br />

6. Ahmad OB, Lopez AD and Inoue M. The<br />

decline in child mortality: a reappraisal.<br />

Bulletin <strong>of</strong> the World Health Organization,<br />

2000, 78 (10): 1175-1191.<br />

7. Khawja M. The extraordinary decline <strong>of</strong><br />

infant and childhood mortality among<br />

Palestinian refugees. Social Science and<br />

Medicine 2004; (58): 463-470.<br />

8. World Health Organization. Facts and<br />

figures from the World Health Report<br />

2005: Make every mother and child count.<br />

1211 Geneva 27, Switzerland: WHO<br />

report; 2007.<br />

9. Etard JF, Hesran J L, Diallo A, Diallo JP,<br />

Ndiaye JL and Delaunay V. Childhood<br />

mortality and probable causes <strong>of</strong> death<br />

using verbal autopsy in Niakhar.<br />

International Journal <strong>of</strong> Epidemiology<br />

2004; 33: 1286–1292.<br />

10. Wagstaff A. Socioeconomic inequalities in<br />

child mortality: comparisons across nine<br />

developing countries. Bulletin <strong>of</strong> the World<br />

Health Organization 2000; 78(1): 19-29.<br />

11. Shaw C, Blakely T, Atkinson J and<br />

Crampton P. Do social and economic<br />

reforms change socioeconomic<br />

inequalities in child mortality? A case<br />

study: New Zealand 1981–1999. Journal<br />

Epidemiolology Community Health 2005;<br />

59: 638-644.<br />

12. UNICEF MENA. Measuring childhood<br />

mortality: A hand book for rapid surveys.<br />

The regional <strong>of</strong>fice in collaboration with the<br />

London school <strong>of</strong> Hygiene and tropical<br />

Medicine; 1988.<br />

13. Haupt A and Kane T. POPULATION<br />

HAND BOOK. Fifth Edition. USA:<br />

Washington, DC; 2004: 14-17.<br />

14. Gordis L. Epidemiology. 1 st edition. USA:<br />

W.B. Saunders Company; 1996: 137-<br />

139.15-National institute for Public Health<br />

and the Environment. Revision <strong>of</strong> the<br />

International Classification <strong>of</strong> Diseases.<br />

Newsletter 2007; 5(1): 1-4.<br />

15. National institute for Public Health and the<br />

Environment. Revision <strong>of</strong> the International<br />

Classification <strong>of</strong> Diseases. Newsletter<br />

2007; 5(1): 1-4.<br />

16. Colorado Department <strong>of</strong> Public Health.<br />

New International Classification <strong>of</strong><br />

Diseases (ICD-10): The History and<br />

Impact. Brief health statistic section.<br />

Annual report Colorado Vital Statistics,<br />

2001; 41.<br />

On the Web: www.cdphe.state.co.us/hs/·<br />

17. Centers for Disease Control and<br />

Prevention. International Classification <strong>of</strong><br />

Diseases 10th Revision (ICD-10).<br />

Department <strong>of</strong> Health and Human<br />

Services. National Center for Health<br />

Statistics report; 2001.<br />

www.cdc.gov/nchs/about/major/dvs/mortd<br />

ata.htm.<br />

18. Collison D, Dey C, Hannah G and<br />

Stevenson L. Income Inequality and Child<br />

Mortality in Wealthy Nations. Journal<br />

Public Health. 2007 ; 29(2): 114-7.<br />

19. Woelk GB, Arrow J, Sanders DM,<br />

Loewenson R and Ubomba-Jaswa P.<br />

Estimating child mortality in Zimbabwe:<br />

results <strong>of</strong> a pilot study using the preceding<br />

births technique. Central Africa Journal<br />

Medicine. 1993; 39(4): 63-70.<br />

20. UNICEF. Situation Analysis <strong>of</strong> Children<br />

and Women In Iraq. UNICEF/Iraq Report;<br />

1998.<br />

21. Ali M, Blacker J and Jones G. Annual<br />

mortality rates and excess deaths <strong>of</strong><br />

children under five in Iraq, 1991-98. World<br />

Health Organization, London School <strong>of</strong><br />

Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, UNICEF<br />

report ; 2003.<br />

22. Vital Statistic Unit. Nineveh Health Office;<br />

2007.<br />

23. Vital Statistic Unit. Al-Khannsa teaching<br />

hospital ;2007.<br />

24. Noymer A. Estimates <strong>of</strong> Under-five<br />

Mortality in Botswana and Namibia: Levels<br />

and Trends. The Botswana DHS: Family<br />

Heath Survey; 1998.<br />

25. Omariba W. Changing childhood mortality<br />

conditions in Kenya: An examination <strong>of</strong><br />

levels, rends and Determinants in the late<br />

1980s and the 1990s. Population studies<br />

© <strong>2009</strong> <strong>Mosul</strong> College <strong>of</strong> Medicine 6

Annals <strong>of</strong> the College <strong>of</strong> Medicine Vol. <strong>35</strong> No. 1, <strong>2009</strong><br />

Centre: <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Western Ontario.<br />

London, Canada; 1998.<br />

26. Singh Kerosene, Karunakra U, Burnham G<br />

and Hill k. Using Indirect Methods to<br />

understand the impact <strong>of</strong> forced Migration<br />

on long –term under-five mortality.<br />

Cambridge <strong>University</strong> Press 2004; 00: 1-<br />

20.<br />

27. Bradshaw D and Dorrington R. Child<br />

mortality in South Africa. Afr Med J<br />

2007; 97(8): 582-3.<br />

28. Al-Haji I, Al-Jawadi A, Al-Neema B.<br />

Mortality <strong>of</strong> under five <strong>of</strong> age in Rawthat<br />

Bany Hamdan. Expermint field services in<br />

Hamam Al- Aleel; 1992.<br />

29. Ahmad WG. Measuring under five<br />

mortality rate in m during the inequitable<br />

Embargo on Iraq. Journal <strong>of</strong> education and<br />

science 2003; 15 (1): 100-105.<br />

30. Linnan M, Anh L, Cuong V, Rahman F,<br />

Rahman A, Shumona S, Sitti-amorn C,<br />

Chaipayom O, Udomprasertgul V, Lim-<br />

Quizon M, Zeng G, Rui-wei J, Liping Z,<br />

Irvine K, Dunn T. Child mortality and injury<br />

in asia: survey results and evidence.<br />

UNICEF :Special Series on Child Injury<br />

2007; 3.<br />

31. National Statistics Office. Infant and child<br />

deaths here are among the highest in<br />

Southeast Asia; high risk fertility behavior<br />

eyed National Demographic and Health<br />

Survey; 2003.<br />

32. Roberts L, Lafta R, Garfield R, Khudhairi<br />

J, Burnham G. Mortality before and after<br />

the 2003 invasion <strong>of</strong> Iraq: cluster sample<br />

survey. Elsevier Ltd; 2004.<br />

http://image.thelancet.com/extras/04art103<br />

42web.pdf 7.<br />

© <strong>2009</strong> <strong>Mosul</strong> College <strong>of</strong> Medicine 7

Annals <strong>of</strong> the College <strong>of</strong> Medicine Vol. <strong>35</strong> No. 1, <strong>2009</strong><br />

Effect <strong>of</strong> amlodipine on serum lipid pr<strong>of</strong>ile<br />

in hypertensive patients<br />

Ashraf H. Ahmed*, Rami M. A. Al-Hayali**<br />

*Department <strong>of</strong> Pharmacology, ** Department <strong>of</strong> Medicine, College <strong>of</strong> Medicine, <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Mosul</strong>.<br />

(Ann. Coll. Med. <strong>Mosul</strong> <strong>2009</strong>; <strong>35</strong>(1): 8-12).<br />

Received: 24 th Oct 2007; Accepted: 30 th Nov 2008.<br />

ABSTRACT<br />

Objectives: To assess the effect <strong>of</strong> amlodipine, as monotherapy, in hypertensive patients, on serum<br />

lipid pr<strong>of</strong>ile, as assessed by serum cholesterol, serum triglyceride, high density lipoprotein cholesterol<br />

(HDLC), and low density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDLC).<br />

Subjects and methods: Thirty three hypertensive patients were included in the study, 25 <strong>of</strong> them<br />

were males and 8 were females. Serum cholesterol, triglyceride, HDLC and LDLC were measured<br />

before and after 2 months <strong>of</strong> starting treatment with amlodipine.<br />

Results: No significant difference could be found between the pre and post treatment levels <strong>of</strong> all<br />

measured parameters.<br />

Conclusion: Treatment with amlodipine does not produce deleterious effect on lipid pr<strong>of</strong>ile, so it may<br />

be a suitable therapy in a hypertensive patient with underlying hyperlipidaemia.<br />

الخلاصة<br />

أهداف البحث: أجريت هذه الدراسة لتقييم تأثير عقار الاملودبين آعلاج أحادي لمرضى ارتفاع ضغط الدم الشرياني على<br />

مستوى الكولسترول، الدهون الثلاثية، البروتين الشحمي عالي الكثافة، والبروتين الشحمي منخفض الكثافة.<br />

المشارآون وطرق العمل: أجريت الدراسة على مريضا مصابا بارتفاع ضغط الدم الشرياني، مريضا منهم من<br />

الذآور و ٨ من الإناث. تم قياس مستوى الكولسترول، الدهون الثلاثية، البروتين الشحمي عالي الكثافة، والبروتين الشحمي<br />

منخفض الكثافة قبل وبعد شهرين من بدء العلاج بعقار الاملودبين.<br />

النتائج: أظهرت نتائج الدراسة عدم وجود فرق معنوي في مستوى القيم المقاسة قبل وبعد العلاج.<br />

الاستنتاج: العلاج بواسطة عقار الاملودبين لايؤثر على مستوى الدهون في الدم وقد يكون علاجا مناسبا لمرضى ارتفاع<br />

ضغط الدم اللذين يعانون من اضطرابات في مستوى الدهون.<br />

٢٥<br />

٣٣<br />

A<br />

rterial hypertension is one <strong>of</strong> the major<br />

risk factors for atherosclerosis and<br />

coronary artery disease, and its treatment has<br />

proved to be beneficial for preventing those<br />

pathologies. Because dyslipidaemia has been<br />

frequently associated with arterial hypertension,<br />

being also a strong risk predictor <strong>of</strong><br />

coronary artery disease, one could assume<br />

that antihypertensive drugs should not have<br />

unwanted effects on lipid pr<strong>of</strong>ile (1) . It has been<br />

suggested that the metabolic side effects <strong>of</strong><br />

antihypertensive drugs are responsible for<br />

their failure to reduce cardiovascular morbidity<br />

in patients with hypertension. Treatment with<br />

some antihypertensive agents may cause<br />

unwanted changes in the lipid pr<strong>of</strong>ile,<br />

attenuating their beneficial antiatherogenic<br />

effects <strong>of</strong> blood pressure reduction (2) . Beta<br />

blockers and thiazids may adversely affect the<br />

lipid pr<strong>of</strong>ile and consequently increase the risk<br />

for coronary atherosclerosis (3,4) . On the other<br />

hand, angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE)<br />

© <strong>2009</strong> <strong>Mosul</strong> College <strong>of</strong> Medicine 8

Annals <strong>of</strong> the College <strong>of</strong> Medicine Vol. <strong>35</strong> No. 1, <strong>2009</strong><br />

inhibitors, such as captopril, seem to have a<br />

neutral effect, or even improve lipid pr<strong>of</strong>ile in<br />

hypertensive hypercholesterolaemic individuals<br />

(5) . Little information is available about the<br />

effect <strong>of</strong> calcium channel blockers, hence, the<br />

present study was undertaken to evaluate the<br />

effect <strong>of</strong> amlodipine, a long-acting<br />

dihydropyridine calcium channel blocker, on<br />

the serum lipid pr<strong>of</strong>ile.<br />

Patients and methods<br />

This study was conducted from April to<br />

August 2007 on a number <strong>of</strong> hypertensive<br />

patients referred from their attending<br />

physicians. The inclusion criteria were as<br />

follows: newly diagnosed hypertensive<br />

patients who did not previously start any<br />

antihypertensive therapy. They should be free<br />

from other organic diseases especially hepatic<br />

and renal diseases. Patient with history <strong>of</strong><br />

heart failure, ischemic heart diseases,<br />

diabetes as well as smokers and alcoholic<br />

were excluded from the study. Their treating<br />

physicians should decide that they need no<br />

other drug apart from the antihypertensive<br />

agent. Out <strong>of</strong> 66 patients, 47 met the above<br />

inclusion criteria and were included in this<br />

study.<br />

Patients were instructed to continue the<br />

same diet which they were taking in the past 2<br />

months prior to commencement <strong>of</strong> the study.<br />

Careful follow up made sure that no drug was<br />

added during the 2 months <strong>of</strong> the study;<br />

especially considering the last 2 weeks.<br />

A total <strong>of</strong> 33 patients successfully completed<br />

the study. Out <strong>of</strong> these, 25 patients were<br />

males and 8 were females. The mean age <strong>of</strong><br />

patients was 40.03 ± 7.63 years, with the<br />

range <strong>of</strong> 28 to 55 years. They received<br />

amlodipine as monotherapy in a mean dose <strong>of</strong><br />

7.27 ± 2.75 mg, ranging from 2.5-10 mg/day.<br />

The lipid pr<strong>of</strong>ile was done before starting the<br />

treatment and at the end <strong>of</strong> 2 months. The<br />

serum was collected in the morning after 14<br />

hours fasting. Serum total cholesterol,<br />

triglycerides, and high density lipoprotein<br />

cholesterol (HDLC) were directly estimated.<br />

The low density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDLC)<br />

was calculated using Freidwald formula.<br />

Paired t-test was used to compare the<br />

differences between the obtained values<br />

before and after treatment.<br />

Results<br />

The effect <strong>of</strong> amlodipine on the lipid pr<strong>of</strong>ile <strong>of</strong><br />

the patients has been shown in table (1). No<br />

significant difference could be found between<br />

the pre and post treatment levels.<br />

Table (1): Effects <strong>of</strong> amlodipine on serum cholesterol, triglycerides, HDLC and LDLC.<br />

Parameters<br />

Before treatment<br />

Mean ± SD<br />

After treatment<br />

Mean ± SD<br />

P value<br />

Total Cholesterol<br />

mg/dl<br />

161.72 ± 27.15<br />

160.45 ± 25.67<br />

NS<br />

Triglycerides<br />

mg/dl<br />

115.72 ± 28.89<br />

116.00 ± 28.25<br />

NS<br />

HDLC<br />

mg/dl<br />

53.93 ± 3.23<br />

54.06 ± 2.68<br />

NS<br />

LDLC<br />

mg/dl<br />

84.48 ± 24.32<br />

83.54 ± 22.60<br />

NS<br />

NS: not significant.<br />

Discussion<br />

The present study reveals no statistically<br />

significant alteration on either serum<br />

cholesterol, triglycerides, HDLC and LDLC<br />

levels.<br />

The effects <strong>of</strong> antihypertensive drugs on lipid<br />

pr<strong>of</strong>ile vary with both the pharmacological<br />

class and the individual drugs. Because<br />

adverse metabolic effects probably reduce the<br />

© <strong>2009</strong> <strong>Mosul</strong> College <strong>of</strong> Medicine 9

Annals <strong>of</strong> the College <strong>of</strong> Medicine Vol. <strong>35</strong> No. 1, <strong>2009</strong><br />

benefit <strong>of</strong> blood pressure reduction therapy<br />

(6,7) , many studies have examined the effects<br />

<strong>of</strong> different antihypertensive agents on lipid<br />

levels. Although there is a general consensus<br />

that thiazide diuretics and nonselective β-<br />

blockers adversely affect lipid levels, many<br />

areas <strong>of</strong> disagreement still exist about the<br />

effects <strong>of</strong> other antihypertensive agents on<br />

lipids. Most authors agree that alpha blockers<br />

(8-12)<br />

reduce triglyceride levels, and many<br />

authors have concluded that ACE inhibitors do<br />

not affect lipids (13-15) .<br />

The findings <strong>of</strong> the current study are in line<br />

with the results <strong>of</strong> other authors (16-19) , as they<br />

all found that calcium antagonists as a group<br />

have no significant effects on lipids. This study<br />

prospectively evaluated the impact <strong>of</strong><br />

amlodipine, as a relatively new calcium<br />

channel blocker, on lipid pr<strong>of</strong>ile in hypertensive<br />

patients, as this drug is increasingly used in<br />

clinical practice.<br />

Drug-induced changes in lipid levels may be<br />

particularly important in hypertensives, since<br />

up to 40 percent <strong>of</strong> untreated patients with<br />

essential hypertension and many patients with<br />

borderline hypertension already have lipid<br />

abnormalities (20) . The relative change in blood<br />

pressure and lipid levels may have different<br />

effects on cardiovascular risk, depending on<br />

baseline levels. Thus, a reduction in blood<br />

pressure in persons with severe hypertension<br />

may decrease risk substantially, even if lipids<br />

are adversely affected. Conversely, treating<br />

mild hypertension with agents that increase<br />

cholesterol levels may be counterproductive<br />

(21) . For the same amount <strong>of</strong> blood pressure<br />

reduction, agents that adversely affect lipids<br />

may cause less reduction in cardiovascular<br />

disease. Indeed, this may partially explain why<br />

trials with diuretics and β-blockers failed to<br />

reduce cardiovascular disease as much as<br />

would have been expected from the degree <strong>of</strong><br />

blood pressure reduction (22) . Whether newer<br />

agents that reduce blood pressure without<br />

adversely affecting lipids will more favorably<br />

affect cardiovascular disease remains to be<br />

proven in controlled clinical trials. Meanwhile,<br />

the result <strong>of</strong> this study provides additional<br />

information suggesting that amlodipine has no<br />

effects on serum lipid pr<strong>of</strong>ile.<br />

In two similarly conducted studies (in Japan<br />

and Brazil), amlodipine did not influence<br />

plasma lipids adversely. In both studies, serum<br />

total, LDL, and HDL cholesterol were not<br />

altered, while serum triglycerides and VLDL<br />

cholesterol were significantly reduced. Similar<br />

beneficial effect on triglycerides level was not<br />

noticed in our study, however (23, 24) .<br />

Beyond the neutral effect <strong>of</strong> amlodipine on<br />

traditional serum lipid pr<strong>of</strong>ile, a new study has<br />

shown that amlodipine significantly reduced<br />

oxidized LDL, an important atherogenic<br />

component <strong>of</strong> LDL (25) .<br />

Studies on rats provided additional favorable<br />

mechanism <strong>of</strong> amlodipine as a vasoprotective,<br />

beyond its blood pressure lowering effect;<br />

where two studies have shown that amlodipine<br />

does not only inhibit atherosclerotic plaque<br />

formation, but also regresses atherosclerosis.<br />

These effects are at least partly due to<br />

inhibition <strong>of</strong> oxidative stress and inflammatory<br />

response (26, 27) .<br />

AVALON study (28) is a recent multicentre that<br />

confirmed the safety, effectiveness, and<br />

tolerability <strong>of</strong> amlodipine and atorvastatin<br />

given together as a single pill for the treatment<br />

<strong>of</strong> coexisting hypertension and<br />

hyperlipidaemia. This is considered the first<br />

version <strong>of</strong> a polypill to treat these two common<br />

disorders.<br />

In conclusion: as far as serum lipid pr<strong>of</strong>ile<br />

was concerned, amlodipine can be considered<br />

a safe antihypertensive drug in hypertensive<br />

patients with dyslipidaemia.<br />

References<br />

1. Kaplan NM. Treatment <strong>of</strong> hypertension:<br />

remaining issues after the Anglo-<br />

Scandinavian cardiac outcomes Trial.<br />

Hypertension 2006; 47: 10-13.<br />

2. Krone w, Nagele H. Effects <strong>of</strong><br />

antihypertensive on plasma lipids and<br />

lipoprotein metabolism. Am Heart J 1988;<br />

116: 1729-1734.<br />

3. Ames RP, Hill P. Raised serum lipid<br />

concentrations during diuretic treatment <strong>of</strong><br />

hypertension: a study <strong>of</strong> predictive<br />

indexes. Clin Sci Mol Med Suppl. 1978;<br />

4:311s-314s.<br />

© <strong>2009</strong> <strong>Mosul</strong> College <strong>of</strong> Medicine 10

Annals <strong>of</strong> the College <strong>of</strong> Medicine Vol. <strong>35</strong> No. 1, <strong>2009</strong><br />

4. Leren P, Helgoland A, Holeme I, Foss PO,<br />

et al. Effect <strong>of</strong> propranolol and prazocin on<br />

blood lipids. Lancet 1980; 2: 4-6.<br />

5. Ferrara LA, Marino LD, Russo O, et al.<br />

Doxazosin and captopril in mildly<br />

hypercholesterolemic hypertensive<br />

patients. The doxazosin- captopril in<br />

hypercholesterolemic hypertensive study.<br />

Hypertension 1993; 21: 97-104.<br />

6. Stokes JD, Kannel WB, Wolf PA, Agostino<br />

RB, et al. Blood pressure as a risk factor<br />

for cardiovascular disease. The<br />

Framingham study-30 years <strong>of</strong> follow up.<br />

Hypertension 1989; 13(5 Suppl): 113-8.<br />

7. Collins R, Peto R, MacMahon S, Hebert P,<br />

et al. Blood pressure, stroke, and coronary<br />

heart disease. Part 2, Short-term<br />

reductions in blood pressure: overview <strong>of</strong><br />

randomized drug trials in their<br />

epidemiological content. Lancet 1990;<br />

3<strong>35</strong>:827-38.<br />

8. Kannel WB, Carter BL. Initial drug therapy<br />

for hypertensive patients with<br />

hyperlipidemia. Am Heart J. 1989;<br />

118:1012-21.<br />

9. Lardinois CK, Neuman SL. The effects <strong>of</strong><br />

antihypertensive agents on serum lipids<br />

and lipoproteins. Arch Intern Med. 1988;<br />

148:1280-8.<br />

10. Weidmann P, Ferrier C, Saxenh<strong>of</strong>er H,<br />

Uehlinger DE, et al. Serum lipoproteins<br />

during treatment with antihypertensive<br />

drugs. Drugs 1988; <strong>35</strong>(Suppl 6):118-34.<br />

11. Giles TD. Antihypertensive therapy and<br />

cardiovascular risk. Are all<br />

antihypertensives equal? Hypertension<br />

1992; 19(1 Suppl):I124-9.<br />

12. Grimm RH Jr. Antihypertensive therapy:<br />

taking lipids into consideration. Am Heart<br />

J. 1991; 122:910-8.<br />

13. Ames RP. Antihypertensive drugs and lipid<br />

pr<strong>of</strong>iles. Am J Hypertens 1988; 1:421-7.<br />

14. Ames RP. The effects <strong>of</strong> antihypertensive<br />

drugs on serum lipids and lipoproteins. I.<br />

Diuretics. Drugs. 1986; 32:260-78.<br />

15. Black HR. Metabolic considerations in the<br />

choice <strong>of</strong> therapy for the patient with<br />

hypertension. Am Heart J. 1991; 121:707-<br />

15.<br />

16. Chait A. Effects <strong>of</strong> antihypertensive agents<br />

on serum lipids and lipoproteins. Am J<br />

Med. 1989; 86(Suppl 1B):5-7.<br />

17. Hunninghake DB. Effects <strong>of</strong> celipridol and<br />

other antihypertensive agents on serum<br />

lipids and lipoproteins. Am Heart J. 1991;<br />

121: 696-701.<br />

18. Raftery EG. The metabolic effects <strong>of</strong><br />

diuretics and other antihypertensive drugs:<br />

a perspective as <strong>of</strong> 1989. Int J Cardiol.<br />

1990; 28:143-50.<br />

19. Verma RB, Chaudhary VK, Jain VK. Effect<br />

<strong>of</strong> calcium channel blockers on serum lipid<br />

pr<strong>of</strong>ile. J Postgrad Med. 1987; 33(2): 65-<br />

68.<br />

20. Julius S, Jamerson K, Mejia A, Krause L,<br />

et al. The association <strong>of</strong> borderline<br />

hypertension with target organ changes<br />

and higher coronary risk. Tecumseh blood<br />

pressure study. JAMA 1990; 264: <strong>35</strong>4.<br />

21. Neaton JD, Wentworth D. Serum<br />

cholesterol, blood pressure, cigarette<br />

smoking, and death from coronary heart<br />

disease. Overall findings and differences<br />

by age for 316,099 white men. Multiple<br />

Risk Factor Intervention Trial Research<br />

Group. Arch Intern Med. 1992; 152:56-64.<br />

22. MacMahon S, Peto R, Cutler J, Collins R,<br />

et al. Blood pressure, stroke, and coronary<br />

heart disease. Part 1, Prolonged<br />

differences in blood pressure: prospective<br />

observational studies corrected for the<br />

regression dilution bias. Lancet. 1990;<br />

3<strong>35</strong>:765-74.<br />

23. Sanjuliana AF, Barraso SG, Fagundes<br />

VGA, Rodriguis MLG, Netto JF, et al.<br />

Moxonidine and amlodipine effects on lipid<br />

pr<strong>of</strong>ile, urinary sodium excretion and<br />

caloric intake in obese hypertensive<br />

patients. Am L Hypertes 2000;13:620-8<br />

24. Ahaneku JE, Sakata K, Urano T, Takada<br />

Y, Takada A. Lipids, lipoproteins, and<br />

fibrinolytic parameters during amlodipine<br />

treatment for hypertension. J Health Sc.<br />

2000;46:455-8<br />

25. Muda P, Kampus P, Teesalu R, Zimer K,<br />

Ristimäe T, Fischer K, et al. Effect <strong>of</strong><br />

amlodipine and candesartan on oxidized<br />

LDL level in patients with mild to moderate<br />

© <strong>2009</strong> <strong>Mosul</strong> College <strong>of</strong> Medicine 11

Annals <strong>of</strong> the College <strong>of</strong> Medicine Vol. <strong>35</strong> No. 1, <strong>2009</strong><br />

essential hypertension. Blood Press<br />

2006;15:313-8<br />

26. Toba H, Nakagawa Y, Milki S, Shimizu T,<br />

Yoshimura A, Inoue R, et al. Calcium<br />

channel blockades exhibit antiinflammatory<br />

and oxidative effects by<br />

augmentation <strong>of</strong> endothelial nitric oxide<br />

synthase and inhibition <strong>of</strong> angiotensin<br />

converting enzyme in N(G)-nitro-L-arginine<br />

methyl ester- induced hypertensive rat<br />

aorta: vasoprotective effects <strong>of</strong> amlodipine<br />

and manidipine. Hypertens Res<br />

2005;28(8):689-700.<br />

27. Yoshii T, Iwai M, Li Z, Chen R, Ide A,<br />

Fukunga S, et al. Regression <strong>of</strong><br />

atherosclerosis by amlodipine via antiinflammatory<br />

and anti-oxidative actions<br />

Hypertens Res 2006;29(6):457-66<br />

28. Messeri FM, Bakris GL, Ferrera D,<br />

Houston MC, Petrella RJ, Flack JM, et al.<br />

Efficacy and safety <strong>of</strong> co administered<br />

amlodipine and atorvastatin in patients<br />

with hypertension and dyslipidaemia;<br />

results <strong>of</strong> the AVALON trial. J Clin<br />

Hypertens (Greenwich) 2006;8(8):571-81.<br />

© <strong>2009</strong> <strong>Mosul</strong> College <strong>of</strong> Medicine 12

Annals <strong>of</strong> the College <strong>of</strong> Medicine Vol. <strong>35</strong> No. 1, <strong>2009</strong><br />

Bell’s palsy in <strong>Mosul</strong><br />

Estabrak M. Alyouzbaki<br />

Department <strong>of</strong> Medicine, College <strong>of</strong> Medicine, <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Mosul</strong>.<br />

(Ann. Coll. Med. <strong>Mosul</strong> <strong>2009</strong>; <strong>35</strong>(1): 13-17).<br />

Received: 4 th Nov 2008; Accepted: 4 th Jan <strong>2009</strong>.<br />

ABSTRACT<br />

Objective: To study the incidence, sex, age, and seasonal distribution <strong>of</strong> Bell’s palsy in <strong>Mosul</strong>.<br />

Methods: A prospective study <strong>of</strong> patients with Bell’s palsy from outpatient and private neurological<br />

clinic and Neurophysiological Unit in Ibn Sena Teaching Hospital in <strong>Mosul</strong> conducted between<br />

September 2001 to August 2003. The patient's age, sex and time <strong>of</strong> occurrence <strong>of</strong> Bell’s palsy were<br />

recorded.<br />

Result: the total number <strong>of</strong> the patients was 469, male patients were 207 and females were 262. The<br />

higher number <strong>of</strong> cases was recorded in the cold months, adult affected more than other age groups.<br />

Conclusion: Bell’s palsy is the commonest cause <strong>of</strong> lower motor neuron facial nerve palsy; herpes<br />

simplex has been claimed as a cause <strong>of</strong> the condition.<br />

Keywords: Bell’s palsy; facial nerve; facial nerve paralysis.<br />

للمرضى الذين أصيبوا بشلل العصب الوجهي (القحفي<br />

الى آب الخلاصة<br />

هذه الدراسة أجريت للفترة من أيلول<br />

السابع) والذين قاموا بمراجعة العيادات الاستشارية والخاصة لأمراض الجملة العصبية في مستشفى ابن سينا التعليمي في<br />

من الإناث<br />

منهم الموصل. وقد وجد ان عدد الذين تم فحصهم ووجدوا انهم يعانون من هذه الحالة المرضية بلغ و٢٠٧ من الذآور، وان أعلى نسبة من الإصابات سجلت في خلال أشهر الشتاء. إلا ان هذا العدد لايمثل العدد الحقيقي<br />

للمرض حيث ان أعدادا آبيرة لاتراجع الأطباء بسبب بعض المعتقدات والتقاليد الخاطئة. آما وجد ان أآثر الأعمار عرضة<br />

للإصابة بهذا الشلل هم البالغون وخصوصا مابين ٢٠-٤٠ سنة. وانها قد تكون نتيجة لإصابة سابقة بفيروسHSV<br />

تنصح هذه الدراسة بمعالجة هذه الحالات مبكرا بعقاقير الكورتيزون ومضادات الفيروسات لتفادي تشوه في الوجه<br />

وخاصة في الحالات الشديدة.<br />

.<br />

٢٦٢<br />

٤٦٩<br />

٢٠٠٣<br />

٢٠٠١<br />

S<br />

ir Charles Bell first described the anatomy<br />

and function <strong>of</strong> the facial nerve in the<br />

(1, 2)<br />

1800s Bell's initial description <strong>of</strong> facial<br />

palsy related to facial paralysis caused by<br />

trauma to the peripheral branches <strong>of</strong> the facial<br />

nerve. However, the terms "Bell's palsy" and<br />

"idiopathic facial paralysis" may no longer be<br />

considered synonymous (3, 4) .<br />

The onset <strong>of</strong> Bell's palsy can be frightening<br />

for patients, who <strong>of</strong>ten fear they have had a<br />

stroke or have a tumor and that the distortion<br />

<strong>of</strong> their facial appearance will be permanent.<br />

Bell’s palsy is the sudden onset <strong>of</strong> unilateral<br />

lower motor neuron dysfunction <strong>of</strong> the seventh<br />

cranial nerve that results in the paralysis <strong>of</strong> the<br />

facial muscles on the affected side <strong>of</strong> the face.<br />

Facial weakness is <strong>of</strong>ten preceded or<br />

accompanied by pain about the ear.<br />

Weakness generally comes on abruptly but<br />

may progress over several hours or even a<br />

day or so. Depending upon the site <strong>of</strong> the<br />

lesion, there may be associated impairment <strong>of</strong><br />

taste, lacrimation, or hyperacusis. There may<br />

be paralysis <strong>of</strong> all muscles supplied by the<br />

© <strong>2009</strong> <strong>Mosul</strong> College <strong>of</strong> Medicine 13

Annals <strong>of</strong> the College <strong>of</strong> Medicine Vol. <strong>35</strong> No. 1, <strong>2009</strong><br />

affected nerve (complete palsy) or variable<br />

weakness in different muscles (incomplete<br />

palsy). Clinical examination reveals no<br />

abnormalities beyond the territory <strong>of</strong> the facial<br />

nerve. Most patients recover completely<br />

without treatment, but this may take several<br />

days in some instances and several months in<br />

others. It is generally accepted that there is<br />

inflammation and oedema <strong>of</strong> the nerve in the<br />

facial canal but, not surprisingly, there have<br />

been few pathological studies. A viral aetiology<br />

is suspected (5-6) . Although Bell’s palsy is a<br />

well-known and relatively common condition,<br />

its epidemiology is unclear.<br />

For this study, we estimated the numbers <strong>of</strong><br />

patients who develop Bell’s palsy and their<br />

distribution along the year. In addition, we<br />

studied the independent effects <strong>of</strong> climate, and<br />

season on the incidence <strong>of</strong> the disease.<br />

Patients and methods<br />

Incident cases were defined as those patients<br />

whose first Bell’s palsy diagnosis occurred<br />

during the study period.<br />

Patients were searched to identify visits that<br />

resulted in a primary diagnosis <strong>of</strong> Bell’s palsy<br />

(International Classification <strong>of</strong> Diseases, Ninth<br />

Revision, Clinical Modification code <strong>35</strong>1.0)<br />

from outpatients and private clinics between<br />

September 2001 to August 2004.<br />

The diagnosis <strong>of</strong> Bell's palsy can usually be<br />

made clinically in patients with (i) a typical<br />

presentation, (ii) no risk factors or preexisting<br />

symptoms for other causes <strong>of</strong> facial paralysis,<br />

(iii) absence <strong>of</strong> cutaneous lesions <strong>of</strong> herpes<br />

zoster in the external ear canal, and (iv) a<br />

normal neurologic examination with the<br />

exception <strong>of</strong> the facial nerve.<br />

The Köppen system, originally developed in<br />

the early 1900s, is a widely recognized and<br />

commonly used climate classification system (7,<br />

8) . The system groups land areas into climatic<br />

categories based on characteristics (e.g.,<br />

extremes, ranges, central tendencies) <strong>of</strong><br />

temperature, rain, and aridity<br />

(9) . For our<br />

analyses, we used the Köppen classification <strong>of</strong><br />

"dry climate" as our single indicator <strong>of</strong> climate,<br />

since it could be directly applied to <strong>Mosul</strong> area<br />

and was not highly correlated with other<br />

factors under investigation (i.e. season).<br />

Result<br />

The total number <strong>of</strong> patients that have been<br />

seen from September 2001 to August 2004<br />

and the distribution <strong>of</strong> patients during the study<br />

period including the number <strong>of</strong> male and<br />

female patients and their percentage are<br />

shown in the following table:<br />

Year<br />

No. <strong>of</strong><br />

patients<br />

Males<br />

Females<br />

2001-02 168 77(45.8%) 91(54.2%)<br />

2002-03 141 59(41.8%) 82(58.2%)<br />

2003-04 160 71(44.3%) 89(55.7%)<br />

469 207(44.1%) 262(55.9%)<br />

The total number <strong>of</strong> patients was 469,<br />

females were affected more than males.<br />

The following chart (No.1) shows the<br />

distribution <strong>of</strong> patients during the months <strong>of</strong><br />

the year which shows peak incidence during<br />

winter months particularly December followed<br />

by January, and there is clear decline <strong>of</strong> the<br />

incidence during hot time especially summer<br />

months:<br />

© <strong>2009</strong> <strong>Mosul</strong> College <strong>of</strong> Medicine 14

Annals <strong>of</strong> the College <strong>of</strong> Medicine Vol. <strong>35</strong> No. 1, <strong>2009</strong><br />

Age distributions <strong>of</strong> the incidence <strong>of</strong> Bell’s<br />

palsy are seen in chart (No. 2), which shows<br />

that peak incidence <strong>of</strong> the condition is mainly<br />

in adult more than young or elderly people.<br />

Discussion<br />

Although Bell’s palsy is a well-known and<br />

relatively common condition, its epidemiology<br />

is unclear. Estimates <strong>of</strong> the incidence <strong>of</strong> this<br />

disease in the United States range from 13 to<br />

34 cases per 100,000 per year (10) ; worldwide,<br />

estimates range from 11.5 to 40.2 cases per<br />

100,000 per year (11) . The number <strong>of</strong> Bell’s<br />

palsy patients which have been recorded in<br />

this study, actually it does not reflect the real<br />

number <strong>of</strong> the condition in our locality as large<br />

number <strong>of</strong> the patients doesn’t consult doctors<br />

because <strong>of</strong> some old religious belief. In<br />

addition to that nearly a similar number <strong>of</strong><br />

patients are seen by GP or physicians and not<br />

neurologist. Most studies have found<br />

comparable rates between males and<br />

females (12) . In this study it is clear that females<br />

were affected more than males; this is in<br />

agreement with a study done in USA where<br />

the incidence rate <strong>of</strong> Bell’s palsy was slightly<br />

higher for females than for males (crude rate<br />

ratio=1.12) (13) . Several studies have suggested<br />

that Bell’s palsy is more common among<br />

young and middle-aged adults (5) , although<br />

others have documented rates that increased<br />

with age (12) but in our study adults affected<br />

more and incidence decreased in middle age<br />

and elderly (chart No. 2). Findings <strong>of</strong><br />

associations between the risk <strong>of</strong> developing<br />

Bell’s palsy and seasonal (11, 14) , geographic (5) ,<br />

racial/ethnic (11) , and environmental (15) factors<br />

have been inconsistent. In this study the<br />

geographical and racial/ ethnic factors were<br />

not included as they need multicenter studies<br />

involving all Iraq.<br />

In this study crude incidence rates during the<br />

colder months <strong>of</strong> the year (November to<br />

March) were consistently higher than the<br />

incidence rates during the warmer months <strong>of</strong><br />

the year (May to September) (chart No.1). This<br />

is in agreement with other studies where Bell’s<br />

palsy rates were relatively high during cold<br />

seasons <strong>of</strong> the year too (13) . While results <strong>of</strong><br />

other studies have been inconsistent in this<br />

regard (5,11, 16,17) ; when seasonal variations in<br />

Bell’s palsy rates were observed, they were<br />

generally lower in summer<br />

There are conflicting reports <strong>of</strong> clustering <strong>of</strong><br />

cases, suggesting an infective aetiology, and<br />

recurring reports implicating herpes viruses (5,<br />

6) , and this may explain the high incidence and<br />

clustering <strong>of</strong> cases reported in this study in<br />

winter months.<br />

There is an agreement that most cases <strong>of</strong><br />

Bell’s palsy are caused by reactivations <strong>of</strong><br />

latent herpes virus type 1 (HSV–1) infections<br />

(11, 12, 18-<br />

<strong>of</strong> geniculate ganglia <strong>of</strong> facial nerves 22) . These reactivations lead to inflammation,<br />

swelling, compression, and ultimately,<br />

dysfunction <strong>of</strong> affected facial nerves. It is<br />

unclear what stimuli most commonly trigger<br />

these reactivations.<br />

If most cases <strong>of</strong> Bell’s palsy are indeed<br />

caused by reactivated herpes virus infections,<br />

then persons with prior HSV–1 infections<br />

should be at higher risk <strong>of</strong> Bell’s palsy than<br />

others in the same populations. In addition,<br />

© <strong>2009</strong> <strong>Mosul</strong> College <strong>of</strong> Medicine 15

Annals <strong>of</strong> the College <strong>of</strong> Medicine Vol. <strong>35</strong> No. 1, <strong>2009</strong><br />

persons with Bell’s palsy should be<br />

demographically similar to those with latent<br />

HSV–1 infections when populations are<br />

uniformly exposed to competent triggers <strong>of</strong><br />

HSV–1 reactivation (13) ; this needs further<br />

evaluations and studies in the future.<br />

One study indicates that two physical<br />

stressors, residence in an arid climate and<br />

exposure to cold, are independent predictors<br />

<strong>of</strong> Bell’s palsy suggest that cold, dry air such<br />

as that in arid areas during winter months, may<br />

traumatize mucus membranes <strong>of</strong> the<br />

nasopharynx, which may, in turn, induce<br />

reactivations <strong>of</strong> herpes infections (13) .This may<br />

explain the increasing incidence <strong>of</strong> Bells” palsy<br />

in cold season in this study particularly if we<br />

knew that there is clear decrease in frequency<br />

and quantities <strong>of</strong> rains in the last decade in<br />

<strong>Mosul</strong> area. This needs future assessment as<br />

we don’t have well documented studies about<br />

the incidence and seasonal variations <strong>of</strong> Bells’<br />

palsy in Iraq in the past where rainy seasons<br />

were longer and heavier. Results from other<br />

studies that examined relations between facial<br />

paralysis and climate were inconclusive (15, 16) ,<br />

although a study reported an incidence rate in<br />

a desert climate was substantially higher than<br />

rates found in most other studies (11, 23) .<br />

One <strong>of</strong> the explanations <strong>of</strong> increased<br />

incidence <strong>of</strong> Bells’ palsy in dry cold weather is<br />

large variations in day-night temperatures<br />

(common in desert environments) and<br />

frequent, sudden, and/or prolonged exposures<br />

to cold outdoor air (common for worker<br />

personnel during winter months) may induce<br />

vasomotor changes in facial areas, initiate the<br />

development <strong>of</strong> edematous neuritis by reflex<br />

ischemia (24) , and/or provoke the reactivation <strong>of</strong><br />

HSV–1 in ganglion cells (25) .<br />

Reactivation <strong>of</strong> latent HSV–1 infections may<br />

be triggered by certain psychological stress,<br />

and this is a well known facts. In this study<br />

there is clear evidence that a psychological<br />

stress may precede the development <strong>of</strong> Bells’<br />

palsy in a good number <strong>of</strong> patients.<br />

Seasonal variation <strong>of</strong> mood due to the effect<br />

<strong>of</strong> changing weather (e.g., seasonal affective<br />

disorder) (26, 27) are well documented.<br />

Furthermore, depression has been<br />

associated with increased susceptibility to<br />

infectious illnesses such as the common cold<br />

(28) . It is possible that immunosuppression<br />

secondary to mood changes may explain<br />

some <strong>of</strong> the seasonal variation in risk <strong>of</strong> Bell’s<br />

palsy (13) .<br />

In conclusion Bell’s palsy is one <strong>of</strong> the<br />

common conditions which affect the facial<br />

nerve especially in late fall and early winter;<br />

early treatment <strong>of</strong> such condition with steroid<br />

and antiviral therapy in addition to<br />

physiotherapy will prevent permanent facial<br />

disfiguring particularly in those severely<br />

affected patients.<br />

References<br />

1. Bell, C. An exposition <strong>of</strong> the natural<br />

system <strong>of</strong> nerves <strong>of</strong> the human body.<br />

Spottiswoode, London 1824.<br />

2. Bell, C. The nervous system <strong>of</strong> the human<br />

body. London: Longman, 1830.<br />

3. James, DG. All that palsies is not Bell's. J<br />

R Soc Med 1996; 89:184.<br />

4. Jackson, CG, von Doersten, PG. The<br />

facial nerve. Current trends in diagnosis,<br />

treatment, and rehabilitation. Med Clin<br />

North Am 1999; 83:179.<br />

5. Morgan M, Nathwant D. Facial palsy and<br />

infection: the unfolding story. Clin Infect<br />

Dis 1992; 14:263–71.<br />

6. Coker NJ. Bell palsy: a herpes simplex<br />

mononeuritis? Arch Otolaryngol Head<br />

Neck Surg 1998; 1247:823–4.<br />

7. Critchfield, H.J. General climatology. 4th<br />

ed. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall,<br />

Inc, 1983.<br />

8. Triantafyllou GN, Tsonis AA. Assessing<br />

the ability <strong>of</strong> the Koeppen system to<br />

delineate the general world pattern <strong>of</strong><br />

climates. Geophys Res Lett 1994;<br />

21:2809–12.<br />

9. Trewartha GT, Horn LH. An introduction to<br />

climate. 5th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-<br />

Hill Book Co, 1980.<br />

10. Bleicher JN, Hamiel S, Gengler JS. A<br />

survey <strong>of</strong> facial paralysis: etiology and<br />

incidence. Ear Nose Throat J 1996;<br />

75:<strong>35</strong>5–8.<br />

11. De Diego JI, Prim MP, Madero R, et al.<br />

Seasonal patterns <strong>of</strong> idiopathic facial<br />

paralysis: a 16-year study. Otolaryngol<br />

Head Neck Surg 1999; 120:269–71.<br />

© <strong>2009</strong> <strong>Mosul</strong> College <strong>of</strong> Medicine 16

Annals <strong>of</strong> the College <strong>of</strong> Medicine Vol. <strong>35</strong> No. 1, <strong>2009</strong><br />

12. Jackson CG, von Doersten PG. The facial<br />

nerve: current trends in diagnosis,<br />

treatment, and rehabilitation. Med Clin<br />

North Am 1999; 83:179–95.<br />

13. Karen E. Campbell and John F. Brundage.<br />