Evidence Based Practice Symposium - McMaster University

Evidence Based Practice Symposium - McMaster University

Evidence Based Practice Symposium - McMaster University

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

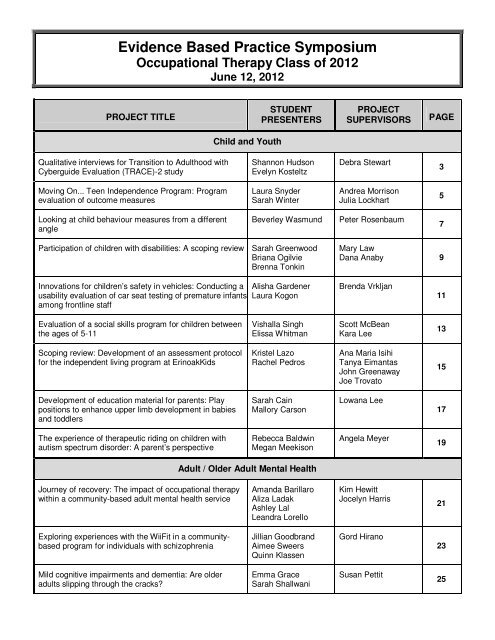

<strong>Evidence</strong> <strong>Based</strong> <strong>Practice</strong> <strong>Symposium</strong><br />

Occupational Therapy Class of 2012<br />

June 12, 2012<br />

PROJECT TITLE<br />

Qualitative interviews for Transition to Adulthood with<br />

Cyberguide Evaluation (TRACE)-2 study<br />

Moving On... Teen Independence Program: Program<br />

evaluation of outcome measures<br />

Looking at child behaviour measures from a different<br />

angle<br />

Child and Youth<br />

STUDENT<br />

PRESENTERS<br />

Shannon Hudson<br />

Evelyn Kosteltz<br />

Laura Snyder<br />

Sarah Winter<br />

Participation of children with disabilities: A scoping review Sarah Greenwood<br />

Briana Ogilvie<br />

Brenna Tonkin<br />

Innovations for children’s safety in vehicles: Conducting a<br />

usability evaluation of car seat testing of premature infants<br />

among frontline staff<br />

Evaluation of a social skills program for children between<br />

the ages of 5-11<br />

Scoping review: Development of an assessment protocol<br />

for the independent living program at ErinoakKids<br />

Development of education material for parents: Play<br />

positions to enhance upper limb development in babies<br />

and toddlers<br />

The experience of therapeutic riding on children with<br />

autism spectrum disorder: A parent’s perspective<br />

Journey of recovery: The impact of occupational therapy<br />

within a community-based adult mental health service<br />

Exploring experiences with the WiiFit in a communitybased<br />

program for individuals with schizophrenia<br />

Mild cognitive impairments and dementia: Are older<br />

adults slipping through the cracks?<br />

PROJECT<br />

SUPERVISORS<br />

Debra Stewart<br />

Andrea Morrison<br />

Julia Lockhart<br />

Beverley Wasmund Peter Rosenbaum<br />

Alisha Gardener<br />

Laura Kogon<br />

Vishalla Singh<br />

Elissa Whitman<br />

Kristel Lazo<br />

Rachel Pedros<br />

Sarah Cain<br />

Mallory Carson<br />

Rebecca Baldwin<br />

Megan Meekison<br />

Adult / Older Adult Mental Health<br />

Amanda Barillaro<br />

Aliza Ladak<br />

Ashley Lal<br />

Leandra Lorello<br />

Jillian Goodbrand<br />

Aimee Sweers<br />

Quinn Klassen<br />

Emma Grace<br />

Sarah Shallwani<br />

PAGE<br />

Mary Law<br />

Dana Anaby 9<br />

Brenda Vrkljan<br />

Scott McBean<br />

Kara Lee<br />

Ana Maria Isihi<br />

Tanya Eimantas<br />

John Greenaway<br />

Joe Trovato<br />

Lowana Lee<br />

Angela Meyer<br />

Kim Hewitt<br />

Jocelyn Harris<br />

Gord Hirano<br />

Susan Pettit<br />

3<br />

5<br />

7<br />

11<br />

13<br />

15<br />

17<br />

19<br />

21<br />

23<br />

25

PROJECT TITLE<br />

Beyond silence: Building support for peer education in a<br />

healthcare workplace<br />

STUDENT<br />

PRESENTERS<br />

Jessica Beaudoin<br />

Nicole Enser<br />

Adult / Older Adult Physical Health<br />

Social participation challenges for women aging with HIV Lisa Blenkhorn<br />

Jennifer Siemon<br />

Participation limitations after distal radius fractures:<br />

Linking with the ICF<br />

The psychometric properties of the MacHANd<br />

Performance Assessment (MPA)<br />

Expert panel review of a community-based exercise<br />

programme for individuals living with chronic obstructive<br />

pulmonary disease (COPD)<br />

Age friendly transit in Hamilton: Assessment using a<br />

travel chain perspective<br />

Technology<br />

Dyan Beavis<br />

Chantelle Glenn<br />

Nikki Lord<br />

Sarah Salter<br />

Elizabeth Landman<br />

Annemarie Muhic<br />

PROJECT<br />

SUPERVISORS<br />

Sandra Moll<br />

Patty Solomon<br />

Seanne Wilkins<br />

Joy MacDermid<br />

Tara Packham<br />

Katie Fisher Kirsti Reinikka<br />

Amanda Enns<br />

Brittany Strauss<br />

Mobile health strategies and occupational therapy Teresa Couto<br />

Lauren Harris<br />

The use of social media by occupational therapists:<br />

Recommendations for the College of Occupational<br />

Therapists of Ontario<br />

Accessibility of the teaching and learning environment at<br />

<strong>McMaster</strong> <strong>University</strong> as perceived by students with<br />

disabilities<br />

Program evaluation of an interprofessional event: Are<br />

we making a difference at <strong>McMaster</strong>?<br />

Reflective journaling: A learning tool for <strong>McMaster</strong><br />

<strong>University</strong> student occupational therapists in the<br />

practicum setting<br />

Through the lens of the male OT student: Motivation<br />

factors to enter the OT profession<br />

Education<br />

Community<br />

Leanne Fernandez<br />

Jessica Yu<br />

Kanishka Baduge<br />

Csilla Gresku<br />

Kait Hammel<br />

Katie Rincker<br />

Kait Toohey<br />

Ashlen Kain<br />

Jackie Bull<br />

Katelin Wakefield<br />

Gawain Tang<br />

Patrick Whalen<br />

Exploring occupational community Erich Bogensberger<br />

Kent Tsui<br />

Lori Letts<br />

Christy Taberner<br />

PAGE<br />

27<br />

29<br />

31<br />

33<br />

35<br />

37<br />

39<br />

Elinor Larney<br />

Bonny Jung 41<br />

Beth Marquis<br />

Bonny Jung<br />

Lorie Shimmell<br />

Bonny Jung<br />

Bonny Jung<br />

Michael Chan<br />

Joyce Tryssenaar<br />

43<br />

45<br />

47<br />

49<br />

51

Transition to Adulthood with Cyberguide Evaluation (TRACE) 2 Research Project<br />

Qualitative study of the use and impact of a transition coordinator and Youth KIT among adolescents with chronic<br />

health conditions.<br />

Authors<br />

Dana Henderson, Shannon Hudson, & Evelyn Kosteltz, MScOT Candidates 2012, <strong>McMaster</strong> <strong>University</strong><br />

Supervisor: Deb Stewart, MScOT Reg. (Ont.)<br />

Acknowledgements<br />

We would like to acknowledge the assistance of Elena Skoreyko Wagner, Deb Stewart, and members of the TRACE<br />

2 study team for their contributions to our research project.<br />

Abstract<br />

Background There is evidence indicating that the transition from pediatric to adult health care for youth with chronic<br />

medical conditions often results in negative outcomes for this population, including poor health care or getting lost<br />

in the system. This evidence demonstrates the current need to enable youth with chronic medical conditions to<br />

effectively transition from the pediatric healthcare setting to the adult healthcare setting. The Transition to<br />

Adulthood with Cyberguide Evaluation (TRACE) study was developed to evaluate the use, utility and impact of two<br />

healthcare transition interventions: the Youth KIT (Keeping it Together for Youth) and an online mentor (called<br />

‘TRACE’) to aid in improving the health care transition planning and practice for youth with chronic medical<br />

conditions. Methods A qualitative phenomenological approach was used to explore the experiences and perceptions<br />

of youth and their caregivers about the Youth KIT© and TRACE mentor in helping the youth transition from<br />

pediatric to adult services. A total of eleven youth and seven caregivers were interviewed. An inductive content<br />

analysis process was used for data analysis using the guidelines of Elo & Kyngas (2007). Results Analysis of the<br />

interview transcripts yielded 9 superordinate themes and related subthemes. Themes included: About the study,<br />

Experiences, Supports, Barriers, Self-management, Parent role, Perceived need, Recommendations, and Overarching<br />

themes of transition . Conclusion Participants did not appear to benefit from the TRACE interventions in relation to<br />

their health care transition. However, there were some benefits regarding general life transitions such as budgeting<br />

and going to school. Revisions to the interventions were recommended by youth and caregivers.<br />

Introduction<br />

There is evidence indicating that for youth with chronic medical conditions the transition from the pediatric<br />

healthcare setting into the adult healthcare setting often results in negative outcomes for this population, including<br />

poor health care or getting lost in the system (Gorter, Stewart, & Woodbury-Smith, 2011; Grant & Pan, 2011). The<br />

Transition to Adulthood with Cyberguide Evaluation (TRACE) study was developed to evaluate the use, utility and<br />

impact of two healthcare transition interventions: the Youth KIT (Keeping it Together for Youth) and TRACE<br />

(CanChild, 2012). The Youth KIT is a tool to aid youth with chronic conditions in obtaining, organizing, and<br />

sharing personal information to promote self-management as they transition into adulthood (CanChild, 2012; Gorter<br />

et al., 2011). TRACE is an online “cyber guide” or mentor that is available to interact with the participants through<br />

Ability Online (CanChild, 2012). The TRACE study is now in its second phase (TRACE 2) and this student project<br />

focused on the qualitative component to evaluate how youth with various chronic medical conditions utilize the two<br />

transition interventions throughout their transition into the adult health care system. This was done by exploring the<br />

experiences and perceptions of the youth and caregivers regarding the TRACE mentor and the Youth KIT, while<br />

also exploring their overall experiences during the transition into the adult health care services (CanChild, 2012).<br />

Literature Review<br />

For youth with chronic conditions, the move from pediatric to adult services, while generally seen as a<br />

logical and welcome aspect of their emerging autonomy (van Staa, Jedeloo, vanMeteren, & Latour, 2011), is often<br />

experienced as a time of adjustment characterized by uncertainty and lack of information and support (van Staa et<br />

al., 2011; Kirk, 2008; Young, Barden, Mills, Burke, Law, & Boydell, 2009). Parents and caregivers of youth with<br />

chronic medical conditions or disabilities express challenges in this transition including feeling unprepared for and<br />

uninvolved in their child’s service transition, and they have concerns regarding continuity of support and expertise<br />

in adult services (Kirk, 2008). Both youth and caregivers have also reported that they feel there is a lack of access to<br />

a variety of health care professionals, lack of professional knowledge, lack of information provided, uncertainty<br />

regarding the transition process, and a need for more information and more support in transitioning to adult care<br />

(Young et al., 2009). <strong>Evidence</strong> reflects that parents are frequently concerned about this transition, as they find it<br />

challenging to step aside and shift roles to allow their youth to accept more responsibility for their self-management,<br />

and feel safer in the pediatric services (Allen, Channon, Lowes, Atwell, & Lane, 2011; van Staa et al., 2011).

Parental resistance to letting their youth become more independent during the transition to adult services is often<br />

cited as a barrier to transition; however, parents are a source of valued social support, and the transition process does<br />

not acknowledge the support and interdependencies frequently found in youth-parent relationships (Allen et al.,<br />

2011).<br />

Methods<br />

A qualitative phenomenological approach was used to explore the experiences and perceptions of youth<br />

and their caregivers about the Youth KIT© and TRACE mentor in helping the youth transition from pediatric to<br />

adult services. Youth already enrolled in the TRACE 1 or TRACE 2 study and their caregivers were recruited for<br />

interviews. A total of eleven youth and seven caregivers agreed to participate in semi-structured interviews<br />

concerning their experiences and perceptions with the Youth KIT© and TRACE mentor. A conventional inductive<br />

content analysis process was used for data analysis.<br />

Results<br />

The study resulted in 9 superordinate themes: About the study: This study found that although the<br />

participants appreciated the availability of the services and supports, these two interventions were not used to their<br />

full capacity. Experiences: Many of the participants were going through multiple transitions and experiences in their<br />

lives. Supports and barriers: The participants reported social, cultural, physical, institutional, transportation,<br />

information, and temporal factors as both supports and barriers for their transitions. Self-management: The majority<br />

of youth reported that they were independent in managing their medical needs and that they saw themselves<br />

becoming more independent in decision-making and directing their own care in the future. Parental role: Many of<br />

the youth continued to receive assistance from their parents. Many parents also reported an understanding and<br />

willingness to allow their youth to become more independent. Perceived need: The majority of participants reported<br />

that although they felt the Youth KIT and online mentor were useful and well organized, they didn’t see a need for<br />

the two resources. They thought it would be better suited for individuals with more significant disabilities or who<br />

lacked supports. Recommendations: The participants recommended having the interventions available through<br />

different mediums, such as a mobile phone application; they also recommended that they be more personalized to<br />

individual needs; and education should be provided to the parents and youth at an earlier stage, prior to transition.<br />

Overarching themes of transition: Multiple transitions were occurring while the youth were transitioning into the<br />

adult health care system including beginning post-secondary school, which seemed to be more of a priority for most<br />

youth.<br />

Conclusions/ Future Directions<br />

This study demonstrates that participating youth and their caregivers did not find the Youth KIT or TRACE<br />

mentor useful in assisting the youth to transition to the adult health care system, although benefits were noted<br />

regarding the assistance provided for other general life transitions. The study also demonstrates the complexity of<br />

the transition including the interdependent relationship between parents and their youth, the perceived need of the<br />

tools during the transition, and the ‘behind the scenes’ support and role that parents play throughout young<br />

adulthood. The Youth KIT and TRACE mentor tools would benefit from revisions based on youth and caregiver<br />

recommendations to improve their utility during the transition from pediatric to adult health care services.<br />

References<br />

Allen, D., Channon, S., Lowes, L., Atwell, C., & Lane, C. (2011). Behind the scenes: The changing roles<br />

of parents in the transition from child to adult diabetes service. Diabetic Medicine, 28, 994-1000.<br />

CanChild: Centre for Childhood Disability Research (2012). TRansition to Adulthood with Cyber guide<br />

Evaluation (TRACE). Retrieved February 29, 2012. from http://www.canchild.ca/en/ourresearch/trace.asp.<br />

Gorter, J. W., Stewart, D., & Woodbury-Smith, M. (2011). Youth in transition: Care, health and<br />

development. Child: Care, Health and Development, 37, 757-763. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2011.01336.x<br />

Grant, C., & Pan, J. (2011). A comparison of five transition programmes for youth with chronic illness in<br />

Canada. Child: Care, Health and Development, 37, 815-820. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2011.01322.x<br />

Kirk, S. (2008). Transitions in the lives of young people with complex healthcare needs. Child: Care,<br />

Health and Development, 34(5), 567-575. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2008.00862.x<br />

Van Staa, A. L., Jedeloo, S., van Meeteren, J., & Latour, J. M. (2011). Crossing the transition chasm:<br />

Experiences and recommendations for improving transitional care of young adults, parents and<br />

providers. Child: Care, Health and Development, 37(6), 821-832. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2011.01261.x<br />

Young, N. L., Barden, W. S., Mills, W. A., Burke, T. A., Law, M., & Boydell, K. (2009). Transition to<br />

adult-oriented health care: Perspectives of youth and adults with complex physical disabilities. Physical &<br />

Occupational Therapy in Pediatrics, 29(4), 349-361. doi: 10.3109/01942630903245994

Acknowledgement: We would like to thank our supervisors<br />

Andrea Morrison, Julia Lockhart, and Deb Stewart along with the<br />

clinical team at the Children’s Developmental Rehabilitation<br />

Programme for their contributions to this project.<br />

Abstract<br />

Moving On…Teen Independence Program: Program Evaluation of Outcome Measures<br />

Purpose: To examine the outcome measures utilized in the<br />

Abstract<br />

Moving On... program for their validity in describing the<br />

outcomes of the program. The Moving On... Teen<br />

Independence Program (MOTIP) is a nine-day program run<br />

by the Children’s Developmental Rehabilitation Programme<br />

(CDRP) in Hamilton, Ontario. This program aims to improve<br />

community-based living skills of adolescents who have a<br />

disability and are preparing to transition to adulthood.<br />

Methods: A retrospective chart review as well as a focus<br />

group with MOTIP clinicians was conducted to examine the<br />

effectiveness of the program and the outcome measures used.<br />

Descriptive statistics, paired samples t-tests and content<br />

analysis were used in the analysis of the data. Results:<br />

Participants experienced significant improvement in their<br />

perception of their performance (p

Results<br />

Population: Participants ranged in age from 15 to 19 years<br />

and had diagnoses of Cerebral Palsy, Spina Bifida,<br />

Progressive Spastic Paraparesis, Chromosomal Abnormalities,<br />

Developmental Coordination Disorder, or Head Injury with<br />

the majority of participants having Cerebral Palsy (73.3% of<br />

all participants). Participants’ GMFCS levels range from level<br />

1 to level 4 with the majority of the participants at level 3 or 4<br />

(both with 33.3% of participants respectively).<br />

COPM: Participants experienced significant improvement in<br />

their perception of performance (p

LOOKING AT CHILD BEHAVIOUR MEASURES FROM A DIFFERENT ANGLE<br />

Beverley Wasmund, MSc. OT candidate 2012; Peter Rosenbaum, MD, CanChild Centre for Childhood Disability Research<br />

Abstract<br />

Current attitudes and theories about child<br />

development, behaviour and disability are considerably<br />

different than they were at the time when many currently<br />

popular behavioural measures were originally developed.<br />

Modern approaches to the clinician-client relationship<br />

emphasize family-centred care and the tenet that parents are<br />

the experts on their child. It is important, therefore, to consider<br />

the history of commonly-used parent-rated behaviour<br />

measures. An awareness of the perspective, structure and<br />

functional capacity of these measures will enable clinicians to<br />

know whether these tools enable them to identify children<br />

with challenging behaviours accurately and measure the<br />

efficacy of interventions. In this paper we examine seven<br />

commonly-used behavioural measures and compare their<br />

features to concerns voiced by parents of children with<br />

challenging behaviours. We conclude with a discussion of an<br />

alternative method for evaluating children’s behaviour.<br />

Introduction<br />

Anecdotal reports from parents suggest that<br />

behavioural screening measures often do not capture their<br />

concerns. Common behavioural questionnaires are based on<br />

data obtained from a variety of test populations but they<br />

cannot possibly account for the unique situation of every child<br />

and their family environment. As a result, some parents find<br />

that their children’s behaviours are dismissed as ‘typical’ and<br />

they do not receive the support they feel they need.<br />

If the behavioural questionnaire is written in a<br />

language other than the first language of the parents, the intent<br />

of some of the questions may be misunderstood. Furthermore,<br />

based on the structure and items of some questionnaires,<br />

parents may not be able to convey adequately what they find<br />

most problematic in a way that is consistent with the content<br />

and format of the questionnaire.<br />

Most behavioural measures focus on specific<br />

behaviours and use closed-ended rather than open-ended<br />

questions. This limits parents’ ability to describe the impact<br />

and meaning of the behaviour on their daily lives. As a result,<br />

many nuances of the problem behaviour may be missed.<br />

Measures designed as diagnostic tools are not<br />

necessarily appropriate as outcome measures unless they have<br />

been validated for that purpose.<br />

With these limitations in mind, we asked the<br />

question: Do current child behaviour assessments measure<br />

what parents find most distressing about their child’s<br />

behaviour? If they do not, it is important to determine how to<br />

identify accurately those in need of service and ensure that the<br />

interventions provided are making a meaningful improvement.<br />

Literature Review<br />

The terms challenging behaviour or problem<br />

behaviour are often used interchangeably. Emerson (2001)<br />

defined challenging behaviour is as follows:<br />

... culturally abnormal behaviour(s) of such an intensity,<br />

frequency or duration that the physical safety of the person or<br />

others is likely to be placed in serious jeopardy, or behaviour<br />

which is likely to seriously limit use of, or result in the person<br />

being denied access to, ordinary community facilities (p. 3).<br />

Emerson also noted, “many challenging behaviours appear to<br />

be functional adaptive responses to particular environments”<br />

(p. 4) and “behaviour can only be defined as challenging in<br />

particular contexts” (p. 8).<br />

Most qualitative research on challenging childhood<br />

behaviour is related to a specific disability such as autism,<br />

ADHD or developmental delay. There is a paucity of literature<br />

describing parents’ perspectives in general terms, i.e.<br />

regardless of what kind of behaviour is occurring, what<br />

characteristics of the behaviour are most distressing to parents.<br />

Researchers who have used qualitative methods to study the<br />

experiences of parents and family members have identified<br />

five common experiences: eternal vigilance, frenetic pace,<br />

worry, social isolation and a distinction between episodic,<br />

dangerous behaviour and more frequent, less dangerous<br />

behaviour described as difficult (Fox, Vaughn, Wyatte &<br />

Dunlap, 2002; Turnbull & Ruef, 1996; Werner Degrace,<br />

2004). Keen and Knox (2004) noted the difficulty of<br />

measuring the efficacy of a behavioural intervention and<br />

suggested that clinicians work “collaboratively with the family<br />

to identify their own measures” (p. 62).<br />

Methods<br />

A database of 520 quantitative, peer-reviewed<br />

research articles dated 1986-2007 from a larger parenting<br />

study served as the basis for this research. Articles which had<br />

titles containing the word ‘behaviour’ were selected. A total<br />

of 43 studies were examined and a short list of the most<br />

frequently-occurring parent-rated measures was generated:<br />

Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) (Achenbach and Edelbrock,<br />

1981), Conners’ Parent Rating Scale (CPRS) (Conners et al.,<br />

1998), Parenting Stress Index – Short Form (PSI-SF) (Abdin,<br />

1995), Questionnaire on Resources and Stress Short Form<br />

(QRSS-SF) (Friedrich, Greenberg, & Crnic,1983), Vineland<br />

Adaptive Behaviour Scales II (Vineland II) (Sparrow,<br />

Cicchetti & Balla, 2005), and Social Skills Rating System<br />

(SSRS) (Gresham & Elliott, 1990). The Social Skills<br />

Improvement System – Rating Scales (SSIS) (Gresham &<br />

Elliott, 2008), a revised version of the SSRS, was used for the<br />

analysis as the original could not be located in the public<br />

domain. Although used less frequently, the Strengths and<br />

Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) (Goodman, 1997), was also<br />

included in this list on the basis of its citation frequency<br />

elsewhere. The measures were compared with respect to the<br />

following features: dates of original and revised versions,<br />

intended population, source of items, test population, % of<br />

positive or prosocial items, % of items related to parents’<br />

experiences or perceptions of their own lives, % of concepts<br />

other than the child’s behaviour, and measurement scale.<br />

Results<br />

Items - Although most child behaviour research<br />

involves children with disabilities, only three of the measures<br />

we examined were developed with data obtained from children<br />

with disabilities (ie., the QRSS-SF, the SSRS, and the<br />

Vineland II). The CBCL, CPRS and SDQ all used data from<br />

child psychiatric clinics in the development of the measures. It<br />

is noteworthy that the PSI, which is based on data from<br />

healthy, typically developing children, is often used in studies<br />

of atypically developing children. Furthermore, although most<br />

of the measures were originally designed to elicit feedback<br />

from parents, the items for the measures were generated by<br />

clinicians, not parents. Authors of the CBCL and QRS-SF

used parents’ responses to their questionnaires to further refine<br />

the questions – but the content came from clinicians. Focus on<br />

problems – The CBCL and PSI-SF do not contain any<br />

positive items and the number of positive items in the CPRS is<br />

in the order of 5%. The QRS and SDQ contain 35% and 40%<br />

positive items, respectively. Only the SSIS and the Vineland II<br />

are weighted more heavily toward positive items. Impact on<br />

parents - Child behaviour and the impact of the behaviour on<br />

parents’ lives are inextricably linked, yet most measures do<br />

not address the impact on parents. Four of the measures<br />

(CBCL, SSIS, SDQ and Vineland II) do not contain any items<br />

related to the parents’ emotions or experiences regarding their<br />

child’s behaviour. Approximately 2% of the questions in the<br />

CPRS pertain to the feelings of the parent; in contrast<br />

approximately 50% of the PSI-SF and 63% of the QRS<br />

address parents’ emotions and experiences. Variable content<br />

- Several measures contained items that appeared to be related<br />

to concepts other than child behaviour. The CBCL, CPRS and<br />

SDQ each contain two items related to the way in which other<br />

people perceive or treat the child. In addition, the CBCL<br />

contains three items related to academic, speech or motor<br />

problems and the QRS contains two items related to the<br />

child’s excess of free time. The CPRS is noteworthy in that<br />

approximately 8% of its items are related to the child’s<br />

learning difficulties. Scaling - All of the measures use a<br />

relatively narrow scale (3 to 5 points) to rate the frequency of<br />

each behaviour. The SSIS is significant in that it rates the<br />

importance of items in addition to their frequency; however, it<br />

does so for the positive items only. Negative items in the SSIS<br />

are rated only with respect to their frequency.<br />

Discussion<br />

The results from our analysis indicate that common<br />

behaviour measures contain items developed primarily from<br />

the clinician’s perspective; emphasize the frequency of<br />

negative behaviours; and generally do not address the impact<br />

of the behaviour on the parents. Given these findings, we<br />

suggest that there are several other important factors to<br />

consider when assessing challenging behaviour and evaluating<br />

the outcome of a behavioural intervention:<br />

• Each child with challenging behaviour and their family is<br />

unique – what is distressing and causes dysfunction for one<br />

family may not be a problem for another family. Thus it is<br />

important to try to acquire an individualized sense of this<br />

child’s behaviour in this family.<br />

• It is not merely the frequency of occurrence that<br />

characterizes a challenging behaviour. Intensity (ranging from<br />

minor to extreme manifestation of the behaviour), safety (i.e.<br />

dangerous versus difficult), duration and social isolation are<br />

also features of the behaviour.<br />

• Eliminating the behaviour entirely may take a very long time<br />

or may not be achievable. Perhaps it is possible to change<br />

some aspects of the behaviour that are most distressing to<br />

parents, and thereby reduce its impact.<br />

• Rather than scoring a large number of behaviours on only<br />

one parameter (i.e. frequency of the behaviour), it may be<br />

more insightful to score a few behaviours in greater detail (i.e.<br />

on several parameters). Each parameter could be scored with<br />

respect to the degree of problem it poses for the parent, i.e. on<br />

a scale of 1 to 10 where 1 represents a slightly problematic<br />

issue and 10 represents an extremely problematic challenge.<br />

This method is similar to that used in the Canadian<br />

Occupational Performance Measure (Law et al., 2005).<br />

The parameters of a particular behaviour might be<br />

defined in the following manner: frequency (how often the<br />

behaviour occurs), amplitude (the intensity with which the<br />

behaviour is manifested), duration (how long a particular<br />

occurrence of the behaviour lasts), location (where the<br />

behaviour occurs), and time of day the behaviour occurs.<br />

There are several advantages to this method of<br />

looking at a child’s problem behaviour. First, parents are able<br />

to focus on a few behaviours of greatest concern to them<br />

rather than a large number of pre-selected behaviours<br />

addressed in the items of standard measures, many of which<br />

may not be relevant to their family at that point in time.<br />

Second, since parents identify the problem behaviours<br />

themselves, the measure is always culturally relevant, never<br />

out-of-date and tailored to the unique situation of each family.<br />

Thus it embodies family-centred practice and the concept that<br />

parents are the experts on their children and the best reporters<br />

of the behaviours and their impact. Third, analysis of various<br />

parameters of the behaviour enhances understanding of the<br />

behaviour and identifies specific aspects of the behaviour to<br />

target for intervention. Finally, use of a 10-point interval scale<br />

rather than scales such as “never/sometimes/often” should<br />

improve the ability of the instrument to measure change.<br />

Conclusion<br />

Popular child behaviour measures tend to measure<br />

the relative frequency with which a large number of possible<br />

behaviours occur. When designing interventions for children<br />

who exhibit challenging behaviours, it may more insightful to<br />

have parents identify a few behaviours of primary concern and<br />

analyze these in greater detail. Given the length of time it<br />

takes to change most challenging behaviours, it may be<br />

possible to improve the situation by addressing the most<br />

problematic features of the behaviour and thereby shape the<br />

behaviour to a more acceptable manifestation. The key<br />

principle described in this paper is to rate each parameter<br />

(frequency, amplitude, duration, location, time of day) with<br />

respect to the degree to which it poses a problem for the<br />

parents.<br />

Key References<br />

Emerson, E. (2001). Challenging behaviour: analysis and<br />

intervention in people with severe intellectual<br />

disabilities (2 nd ed.). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge<br />

<strong>University</strong> Press.<br />

Fox, V., Vaughn, B.J., Wyatte, M.L., & Dunlap, G. (2002).<br />

We can’t expect other people to understand: Family<br />

perspectives on problem behaviour. Exceptional<br />

Children, 68, 437-450.<br />

Keen, D., & Knox, M. (2004). Approach to challenging<br />

behaviour: A family affair. Journal of Intellectual &<br />

Developmental Disability, 29, 52-64.<br />

Turnbull, A.P., &Ruef, M. (1996). Family perspectives on<br />

problem behavior. Mental Retardation, 34, 280-293.<br />

Werner DeGrace, B. (2004). The everyday occupation of<br />

families with children with autism. American Journal<br />

of Occupational Therapy, 58, 543-550.<br />

Acknowledgements<br />

The authors wish to thank Dr. Lucyna Lach for<br />

providing the database, Dr. Nora Fayed for her advice<br />

regarding analysis of measures and N. Nemeth whose<br />

observations and insights served as the catalyst for this project.

Participation in Children and Youth with Disabilities:<br />

A scoping review<br />

Briana Ogilvie, Sarah Greenwood & Brenna Tonkin, MSc. OT Candidates 2012, <strong>McMaster</strong> <strong>University</strong><br />

Project supervisor: Mary Law, PhD, OT Reg. (Ont)<br />

Abstract<br />

Introduction<br />

Pg. 1<br />

Methods

Results<br />

Discussion Conclusion<br />

Pg. 2<br />

2<br />

Donec sit amet arcu.

Innovations for Children’s Safety in Vehicles:<br />

Conducting a Usability Evaluation of Car Seat Testing of Premature Infants Among Frontline Staff<br />

Project Supervisor: Brenda Vrkljan PhD, OT, Reg. (Ont).<br />

Students: Laura Kogon MSc OT Candidate 2012 & Alisha Gardener MSc OT Candidate 2012<br />

Abstract: Preterm infants are at higher risk for health complications when in a semi-upright position, which is the common<br />

position for automobile travel using car seats. 1, 2 Guidelines have been established for these infants to minimize the risk by<br />

ensuring the infant is optimally positioned in their car seat. The purpose of this study is to describe a positioning protocol<br />

implemented by nurses in a neonatal intensive care unit (NICU), prior to infant discharge. In order to capture the nurses’<br />

behaviours, a usability checklist was developed. This checklist was utilized to quantify and qualify the nurse’s behaviours<br />

when positioning an infant in their car seat. Four nurses and four infants were recruited by a sample of convenience. Data was<br />

collected through videotapes and questionnaires. Results from the study demonstrate that there are consistencies and<br />

inconsistencies in nursing behaviours when positioning an at-risk infant in their car seat, despite the availability of positioning<br />

guidelines. Limitations and implications for practice are discussed.<br />

Introduction: Motor vehicle collisions are a leading cause of<br />

death for young children in Canada. 1 Determining effective<br />

strategies that optimize positioning of infants in car seats has<br />

become a focus of both researchers and policy makers. When<br />

car seats are used correctly in motor vehicle collisions, there is a<br />

71% reduced risk of infant mortality and 67% reduced risk of<br />

injury. 3 Infants born prematurely have been identified as having<br />

an even higher risk when positioned in a semi-upright position,<br />

as required by most car seats 3 . These risks include:<br />

• Apnoea (temporary absence/cessation of breathing) 2,4,5<br />

• Bradycardia (slow heartbeat) 2,4,5<br />

• Hypoxia 2,4,5<br />

• Problems with the size and ‘fit’ of the car seat itself. 4,5<br />

To ensure premature infants are safe for travel by car seat, the<br />

Infant Car Seat Challenge (ICSC) has been recommended by the<br />

American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP). The ICSC is designed<br />

to assess the safety of at-risk infants in their car seat prior to<br />

hospital discharge. Guidelines for ICSC suggest that any infant<br />

born at less than 37 weeks gestation or who has respiratory<br />

complications endure a 90 minute observation period in their car<br />

seat prior to discharge 6 .<br />

Literature Review: Guidelines have been developed by<br />

Transport Canada and the Canadian Pediatric Society (CPS) to<br />

outline some recommendations on appropriate positioning<br />

strategies for preterm and low-birth weight infants. Key points<br />

include:<br />

• Use of blanket rolls to fill space at head, crotch, sides<br />

• Shoulder straps originate at or slightly below the shoulder<br />

and should be tightened to 1 finger width at collarbone<br />

• Infant should not wear bulky clothing (e.g., snowsuit)<br />

• Buttocks should be positioned at the back of the seat<br />

• The use of a 5-point harness<br />

• Chest clip positioned at armpit level<br />

• Car seat positioned at a 45 degree angle in vehicle as well as<br />

during in-hospital, pre-discharge ICSC evaluation<br />

• Car seat positioned on the floor during in-hospital evaluation<br />

Despite the availability of these guidelines, there is no available<br />

evidence confirming how nurses actually position these infants<br />

in their respective car seats. Clinical procedures involved with<br />

preparing preterm/at-risk infants for discharge range from<br />

formal ICSC testing to caregiver car seat education. Common<br />

across hospitals is an understanding on how to best position<br />

these infants in their car seats in preparation for discharge.<br />

Project Objective:<br />

To describe the positioning protocol implemented by nurses<br />

prior to the discharge of preterm and/or at-risk infants.<br />

Research Question: What are nurses in an Ontario hospital<br />

doing to position premature/at-risk infants in their car seat prior<br />

to hospital discharge?<br />

Methods:<br />

Study Design: Concurrent nested strategy (Mixed Methods):<br />

This design allows for collection of quantitative and qualitative<br />

data to occur simultaneously using a single source of data 7 .<br />

Participants: A total of 4 videos were analyzed that featured:<br />

4 nurses employed in a level 2 nursery in Ontario and 4 infants<br />

ready for discharge.<br />

Data collection stages:<br />

1) Questionnaires: Provided to the nurses and the infant’s family<br />

to obtain demographic information<br />

2) Videotapes: Recorded videos of each nurse positioning an<br />

infant into their car seat<br />

3) Creation (& Validation) of a Usability Checklist: Developed<br />

using a task-analysis of infant car seat positioning strategies<br />

utilized by nurses in the videos<br />

Validation of checklist:<br />

• Two registered nurses were recruited through a sample of<br />

convenience and were provided with identical training on how<br />

to use the usability checklist.<br />

• Inter-rater reliability (Kappa): 95.7% (excellent) 8<br />

Data Analysis: The usability checklist was used as a tool to<br />

describe and document the observed/heard behaviours<br />

throughout the videos. This checklist was used to collect<br />

objective data that was then tabulated and used to quantify nurse<br />

behaviours. Both qualitative and quantitative data collected<br />

using the usability checklist was then utilized to identify<br />

consistencies and inconsistencies in nurses’ verbal and nonverbal<br />

behaviours.<br />

Results:<br />

Demographic Information: Clinical experience in the NICU and<br />

with car seat testing ranged from three months to 23 years.

Results (Cont’d)<br />

Key Areas of Infant Positioning from the Usability Checklist:<br />

✔ Indicates a positioning guideline that was implemented by a nurse<br />

✗ Indicates a positioning guideline that was not implemented by a nurse<br />

# of<br />

Nurses<br />

Positioning Guidelines<br />

Car Seat Setup:<br />

✔✔✔✔ Car seat contained a five-point harness<br />

✗✗✗✗<br />

Discussed or ensured that the car seat was<br />

positioned at a 45 degree angle<br />

✗✗✗✗ Positioned the car seat on the floor<br />

Fastening the Infant in the Car Seat:<br />

Positioned the chest clip at the infant’s armpit<br />

✔✔✔✔ level<br />

Ensured the infant’s bottom was positioned at<br />

✔✔✔✔ the back of the car seat<br />

✔✔✔✗<br />

Ensured the infant was not wearing bulky<br />

clothing<br />

✔✔✗✗<br />

Ensured that the shoulder straps originated at<br />

(or slightly below) the infant’s shoulders<br />

✔✔✗✗<br />

Tightened the shoulder straps to one finger<br />

width at the infant’s collarbone<br />

Truck Positioning:<br />

✔✔✔✗ Checked for extra space at the crotch<br />

When extra space was identified at the crotch,<br />

✔✔✗✗<br />

rolled towels/blankets were positioned at the<br />

crotch to prevent submarining<br />

Consultation:<br />

✔✔✔✔<br />

Provided the caregiver(s) with education<br />

regarding proper car seat positioning strategies<br />

✗✗✗✗ Consulted with another healthcare professional<br />

Discussion: Ensuring premature infants are optimally positioned<br />

in their car seat is a priority. Current practice recommendations<br />

from the CPS, Transport Canada, and the Ontario Ministry of<br />

Transportation (MTO) support many of the nurse practices<br />

observed throughout the four videos. It is evident that all nurses<br />

included in this study were committed to providing the infant<br />

and their caregivers with car seat safety education and<br />

positioning strategies. All the nurses had knowledge of the<br />

hospital’s protocol for infant car seat positioning, which was<br />

evident from the checklist analysis.<br />

Positioning premature infants in car seats remains challenging:<br />

Despite the availability of positioning recommendations through<br />

CPS, Transport Canada, MTO, and hospital guidelines, evidence<br />

from this study suggests that hospital protocols and nursing<br />

behaviours are not always consistent with these<br />

recommendations. This was evident by the inconstancies found<br />

in nursing practices throughout the videos.<br />

Clinical Implications:<br />

Nurse Training: Findings indicate that there is no standardized<br />

training provided to nurses as demonstrated by the inconsistent<br />

nurse behaviours. The discrepancies between the nurses’<br />

behaviours observed in this study highlight a need for more<br />

resource allotment for educating and training nurses on infant<br />

car seat safety.<br />

Quality Control: Given the importance of proper positioning<br />

strategies for infant safety, it is important to ensure that each<br />

infant and caregiver receive positioning strategies that are<br />

consistent with practice recommendations. This research<br />

highlights a need for developing hospital protocols to promote a<br />

consistent quality of care. For example, incorporating a usability<br />

checklist similar to the one proposed in this study can assist in<br />

guiding and monitoring nurse practices.<br />

Future Directions for Clinical Research:<br />

• Exploring what different hospitals are doing across the<br />

province to position an infant in their car seat would provide a<br />

broader sense of current practices.<br />

• Future research should focus on reviewing the relationship<br />

between caregiver education and infant car seat positioning<br />

and safety.<br />

• Research should explore what nurses are specifically doing to<br />

position an infant in preparation for the ICSC and implications<br />

for pass/fail.<br />

Limitations:<br />

As videotapes were used as a primary method for data<br />

collection, error and bias may be a limiting factor of this study.<br />

This error and bias exists, as participants may act differently<br />

when they know they are being videotaped and/or actions may<br />

not have been accurately captured during the videos. In addition,<br />

usability testing identifies n=5 is ideal for ensuring saturation,<br />

however this study included n=4. For this reason, sample size is<br />

a potential limitation of this study.<br />

Conclusions: This pilot study is the first to actually evaluate<br />

how nurses position premature or at-risk infants in their car seat,<br />

prior to discharge from the NICU. Further research is needed to<br />

provide a basis to support changes in hospital protocol that will<br />

support consistent training, quality assurance, and knowledge<br />

translation amongst frontline staff.<br />

Acknowledgements: We would like to thank the following<br />

individuals for their guidance: Brenda Vrkljan, PhD, OT,<br />

Catherine Moher, MSc, RN & Heather Boyd, MSc, OT.<br />

References:<br />

1. Public Health Agency of Canada. (2008). Leading Causes of<br />

Death and Hospitalization in Canada. Retrieved from<br />

http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/publicat/lcd-pcd97/index-eng.php1<br />

2. Bull, M., & Engle, W. (2009). Safe transport of preterm and<br />

low birth weight infants at hospital discharge. American<br />

Academy of Pediatrics, 123, 1424-1429.<br />

3. Transport Canada. (2008). Transporting infants and children<br />

with special needs in personal vehicles: A best practices guide<br />

for healthcare practitioners. Retrieved March 23, 2012 from<br />

http://www.tc.gc.ca/media/documents/roadsafety/TP14772e.pdf<br />

4. Lincoln, M. (2005). Car seat safety: Literature review.<br />

Neonatal Network, 24, 29-31.<br />

5. Canadian Pediatric Society, (2000). Assessment of babies for<br />

car seat safety before hospital discharge. Paediatric Child<br />

Health, 5, 53-56.<br />

6. Howard-Salsman, K., (2006). Car seat safety for high-risk<br />

infants. Neonatal Network, 25, 117-129.<br />

7. Creswell, J.W. (2003). Research design: Qualitative,<br />

quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. (2nd ed.).<br />

Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.<br />

8. Fleiss, J. L. (1981). Statistical methods for rates and<br />

proportions. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

Abstract<br />

Evaluation of a Social Skills Program for Children Between the Ages 5-11<br />

By: Vishalla Singh and Elissa Whitman, MSc (OT) Candidates (2012), <strong>McMaster</strong> <strong>University</strong><br />

Supervisors: Kara Lee and Scott McBean, Occupational Therapists, George Jeffrey Children’s Treatment Center<br />

Background: According to the World Health Organization (WHO) International Classification of Function (ICF), social<br />

participation is an aspect of healthy living and can be fostered within activity groups (WHO, 2001). The literature supports the<br />

effectiveness of social skills training and many outcome measures have been developed to assess social skills. However, it remains<br />

unclear as to what outcome measure is most appropriate for measuring social skills. Purpose: The purpose of this project was to<br />

recommend a social skills outcome measure that clinicians at the George Jeffrey Children’s Centre (GJCC) could use to evaluate<br />

change in the social skills of children (5-11) participating in a Social Skills Programs offered at the Centre. Methods: Firstly, a<br />

comprehensive literature review was executed to determine what social skills outcome measures currently exist. Secondly, 7<br />

criteria were established in order to choose the most relevant outcome measure for the GJCC Social Skills Program. Thirdly, the<br />

limitations of the chosen outcome measure were addressed through the creation of a Clinician Outcome Measure and a Self-<br />

Reflection Scale. Findings: 37 pediatric social skills measures were found in the literature review. <strong>Based</strong> on the 7 pre-determined<br />

criteria, the Social Skills Rating System (SSRS) was determined to be most appropriate. Two limitations were noted with the<br />

SSRS: lack of a clinician report tool and no self-report measure for children 8 and below. These limitations were addressed<br />

through the creation of a Self-Reflection Scale for children under the age of 8 and a Clinician Outcome Measure. Directions for<br />

future research are discussed. Conclusions: Findings revealed that the SSRS was the most appropriate outcome measure for use<br />

with the GJCC Social Skills Program. The SSRS combined with the Clinician Outcome Measure and Self-Reflection Scale will<br />

allow clinicians at GJCC to evaluate change in children’s social skills over time.<br />

Part 1: Literature Review<br />

Introduction<br />

The purpose of the project was to determine whether an<br />

adequate outcome measure to assess social skills existed that<br />

met the needs of the Social Skills Program at GJCC (for<br />

children 5-11 of various diagnoses, offers 3 levels of<br />

programming). Therefore, we conducted a literature review,<br />

which indicated that group-based social skills interventions<br />

can have a positive impact on the development of social skills<br />

for many individuals experiencing social skills deficits<br />

(Castorina & Negri, 2011; Cotugno, 2009; Koenig et al.,<br />

2010; Reichow & Volkmar, 2009; White, Koenig & Scahill,<br />

2007). In addition, there are currently 37 pediatric social<br />

skills measures that were found in the literature. One of the<br />

limitations of measuring the effectiveness of social skills<br />

groups identified in the literature is a lack of valid, reliable,<br />

and sensitive outcome measures to evaluate social skills<br />

(White, Koenig, & Scahill, 2007). The most relevant<br />

measures were selected based on 7 criteria (see below).<br />

Methods<br />

We used the focused clinical question: what outcome<br />

measures are being used to evaluate social skills? The search<br />

strategy was as follows: (1) 14 databases searched; (2)<br />

inclusion criteria: published in English, available through the<br />

<strong>McMaster</strong> libraries, involved a social skills program, and<br />

reported an outcome measure related to social skills; (3)<br />

exclusion criteria: adjunct studies that explicitly involved a<br />

medical intervention in addition to a social skills intervention.<br />

We also contacted all of the Ontario Association of<br />

Children’s Rehabilitation Services (OACRS) members to<br />

determine if they were using any social skills assessments.<br />

Criteria considered when selecting the most relevant outcome<br />

measure were: (1) good reliability; (2) good validity; (3) good<br />

clinical utility; (4) used in 3 or more studies; (5) used for<br />

children 5-11; (6) used with multiple diagnoses; and (7) used<br />

in a variety of environments (i.e. home, school, and therapy<br />

sessions).<br />

Results and Discussion<br />

Five social skills measures (see Table 1) met 4 or more of the<br />

criteria and were further reviewed.<br />

Table 1: Summary of relevant social skills measures.<br />

Autism Social<br />

Skills Profile<br />

(ASSP)<br />

Social<br />

Responsiveness<br />

Scale (SRS)<br />

Social Skills<br />

Rating System<br />

(SSRS)<br />

Matson<br />

Evaluation of<br />

Social Skills for<br />

Youngsters<br />

(MESSY)<br />

Structured Role-<br />

Play<br />

Assessments<br />

• Description: Likert scale; completed<br />

by parents; measures frequency of<br />

social behaviours; designed for<br />

social skills groups; 6-17; Autism.<br />

• Met 4/7 criteria.<br />

• Description: diagnostic tool;<br />

completed by clinician; measures<br />

severity of social impairment; 4-18;<br />

Autism.<br />

• Met 5/7 criteria.<br />

• Description: Likert scale; completed<br />

by parents, teachers, and participant;<br />

measures frequency of social<br />

behaviours; 3-18; multiple<br />

diagnoses.<br />

• Met 7/7 criteria.<br />

• Description: Likert scale; completed<br />

by parents, teachers, and participant;<br />

measures frequency of social<br />

behaviours; 4-18; multiple<br />

diagnoses.<br />

• Met 5/7 criteria.<br />

• Description: observable behaviours<br />

of social skills within a structured<br />

setting.<br />

• Met 4/7 criteria.<br />

Since the SSRS met all 7 criteria, it was determined to be<br />

most appropriate for the GJCC Social Skills Program.<br />

However, 2 limitations were noted: (1) no self-report measure<br />

for children below 8, and (2) no clinician tool for measuring<br />

change in the participants’ social skills.<br />

1

Issue Part 2: #: Development [Date] of Self-Reflection Scale and Clinician Outcome Measure<br />

Dolor Sit Amet<br />

Introduction<br />

To address the limitations identified in the SSRS in part 1 of<br />

the project, the following tools were developed:<br />

(1) Self-Reflection Scale – the purpose of the scale is to allow<br />

clinicians at the GJCC to ascertain the child’s (8 and under)<br />

perception of their own social skills.<br />

(2) Clinician Outcome Measure – the purpose of the measure<br />

is to allow clinicians at the GJCC to measure changes in<br />

children’s social skills throughout the sessions offered in the<br />

Social Skills Program.<br />

Methods<br />

The Self-Reflection Scale was created with reference to a 4point<br />

Likert scale self-report measure developed by another<br />

member of the Ontario Association of Children’s<br />

Rehabilitation Centers (OACRS) (A. DeFinney, personal<br />

communication, Feb. 28, 2012). Changes were made to the<br />

scale so that questions were aligned with the GJCC social<br />

skills program and reflected previous research uncovered<br />

during the literature search in part 1, i.e. a list of commonly<br />

observed behaviours used in social skills assessments.<br />

With respect to the Clinician Outcome Measure, clinicians at<br />

the GJCC requested that a Likert scale be used since it would<br />

provide an ordinal measurement of subjective clinical<br />

evaluations (K. Lee & S. McBean, personal communication,<br />

March 14, 2012). Therefore, a brief literature review<br />

regarding the ideal number of response categories that should<br />

make up a rating scale was undertaken.<br />

Results and Discussion<br />

The Self-Reflection Scale was created for children below the<br />

age of 8 to report on their perception of their own social<br />

skills.<br />

With regards to the Clinician Outcome Measure, the evidence<br />

suggested that overall reliability, validity, and discriminating<br />

power are significantly higher for Likert scales with response<br />

categories of 7 points (Preston & Colman, 2000). The<br />

Clinician Outcome Measure consists of the following:<br />

(1) Three sections – one for each social skills group offered<br />

within the GJCC Social Skills Program; and<br />

(2) Two scales – one that measures the extent to which the<br />

child can describe a particular social skill (Descriptive Scale),<br />

and one that measures the degree of independence the child<br />

has when performing a particular social skill (Implementation<br />

Scale).<br />

Conclusion<br />

The SSRS met 7/7 criteria, but had 2 limitations that were<br />

addressed through the creation of a Self-Reflection Scale and<br />

Clinician Outcome Measure.<br />

Future Directions<br />

Future directions may include the following:<br />

(1) Trial the SSRS for the Social Skills Program (currently<br />

being done at GJCC);<br />

(2) Trial the Clinician Outcome Measure for the Social Skills<br />

Program (currently being done at GJCC);<br />

(3) Trial the Self-Reflection Scale for the Social Skills<br />

Program (currently being done at GJCC);<br />

(4) If the SSRS is an appropriate outcome measure for the<br />

Social Skills Program, use the SSRS to determine the<br />

effectiveness of the Social Skills Program;<br />

(5) Determine the reliability and validity of the Clinician<br />

Outcome Measure; and<br />

(6) Determine the reliability and validity of the Self-Reflection<br />

Scale.<br />

References<br />

Castorina, L.L., & Negri, L.M. (2011). The inclusion of<br />

siblings in social skills training groups for boys with<br />

Asperger syndrome. Journal of Autism and Developmental<br />

Disorders, 41, 73-81.<br />

Cotugno, A.J. (2009) Social competence and social skills<br />

training and intervention for children with Autism Spectrum<br />

Disorders. Journal Autism and Developmental Disorders,<br />

39, 1268-1277.<br />

Koenig, K., White, S.W., Pachler, M., Lau, M., Lewis, M.,<br />

Klin, A., & Scahill, L. (2010). Promoting social skill<br />

development in children with pervasive developmental<br />

disorders: A feasibility and efficacy study. Journal of<br />

Autism and Developmental Disorders, 40, 1209-1218.<br />

Preston, C.C., & Colman, A.M. (2000). Optimal number of<br />

response categories in rating scales: reliability, validity,<br />

discriminating power, and respondent preferences. Acta<br />

Psychologica, 104, 1-15.<br />

Reichow, B. & Volkmar, F.R. (2010). Social skills<br />

interventions for individuals with autism: Evaluation for<br />

evidence-based practices within a best evidence synthesis<br />

framework. Journal of Autism and Developmental<br />

Disorders, 40, 149-166.<br />

White, S. W., Koenig, K., & Scahill, L. (2007). Social skills<br />

development in children with autism spectrum disorders: A<br />

review of the intervention research. Journal of Autism<br />

Developmental Disorders, 37, 1858-1868.<br />

World Health Organization (WHO). (2001). International<br />

Classification of functioning, disability, and health<br />

(IFC). Geneva, Switzerland: World Health<br />

Organization.<br />

Acknowledgements<br />

We would like to thank Kara Lee and Scott McBean for their<br />

enthusiasm and guidance throughout this project and for<br />

allowing us to become involved with the Social Skills Program.<br />

We appreciate the input provided by Kerstin Blazina and Kate<br />

Clower, Speech Language Pathologists, during the<br />

development of the descriptive scale for the Clinician Outcome<br />

Measure. Finally, it was a pleasure to work alongside the<br />

dedicated staff at GJCC.<br />

Link to Prezi<br />

http://prezi.com/tzss6jsazy99/social-skills-outcome-tool/<br />

2<br />

2

Scoping Review: Development of an Assessment Protocol for the<br />

ErinoakKids Independent Living Program<br />

Student Investigators: Kristel Lazo & Rachel Pedros, MSc OT Candidates 2012, <strong>McMaster</strong> <strong>University</strong><br />

Project Supervisors: Anna Maria Isihi, OT Reg (Ont), Jon Greenaway, SW, Joe Trovato, M.A., C. Psyche Associate, &<br />

Tanya Eimantas, BScOT, MSc, OT Reg (Ont)<br />

ABSTRACT: Purpose: To determine which skills or characteristics best promote independent living in youth with disabilities and<br />

revise an assessment protocol for the ErinoakKids Centre for Treatment and Development Independent Living Program (ILP) that<br />

measures these skills. Method: A scoping review was conducted to explore research published from 1980 through to 2011 that<br />

pertained to the determinants of independent living. Studies included participants with physical or intellectual disabilities, focused on<br />

personal skills or characteristics, and examined the transition to adulthood/independent living. The authors identified assessments that<br />

measure key factors and reviewed the psychometric properties of the most suitable assessments. Current ILP assessment protocol was<br />

revised. Results: Twelve studies met the inclusion criteria. Self-determination and social skills were found to be significant factors<br />

associated with positive independent living outcomes. The recommendations for the revised assessment protocol included the addition<br />

of the Arc’s Self-Determination Scale and the Social Skills Improvement System Rating Scale (SSIS-RS). Conclusion: It is<br />

recommended that the ErinoakKids Centre for Treatment and Development ILP incorporate measures of self-determination and social<br />

skills, as these are important personal characteristics contributing to successful independent living outcomes.<br />

Introduction<br />

Successful transition into independent living is a critical stage<br />

in development for adolescents with disabilities (Healy &<br />

Rigby, 1999). Research has shown that adults with disabilities<br />

are less likely to engage in paid employment, participate in<br />

recreational activities and also experience difficulty navigating<br />

the adult health care system and accessing community supports<br />

(Stewart, Law, Rosenbaum, & Wills, 2001). To assist<br />

adolescents with disabilities throughout the transition process,<br />

many children’s treatment centres (CTC) across Ontario have<br />

developed programs that aim to facilitate and foster<br />

independent living. The term “independent living” stems from<br />

a philosophy founded on the premise that individuals with<br />

disabilities have the right to make personal decisions that<br />

impact all areas of their life (Centre for Independent Living in<br />

Toronto, 2012). Research into independent living examines<br />

various post-school outcomes, such as continuing education,<br />

employment, and community involvement (Test, Mazzotti,<br />

Mustian, Fowler, Kortering, & Kohler, 2009). The Independent<br />

Living Program (ILP) at ErinoakKids Centre for Treatment<br />

and Development aims to enable youth with physical<br />

disabilities to achieve personal goals and develop a set of<br />

essential life skills (ErinoakKids, 2012). The ILP is an<br />

overnight program where participants between the ages of 16<br />

and 19 live within a college residence for approximately ten<br />

days with personal care support (ErinoakKids, 2012).<br />

Literature supports the effectiveness of independent living<br />

programs; however, limited research is available that examines<br />

the correlations between personal characteristics and<br />

independent living. Understanding what personal<br />

characteristics best promote independent living will enable<br />

independent living programs to assess these skills and develop<br />

appropriate interventions. To address this gap in literature, the<br />

following research question was developed: What compilation<br />

of assessments is best suited to measure the skills and<br />

characteristics essential to independent living for adolescents<br />

with disabilities entering the Independent Living Program at<br />

ErinoakKids? The purpose of this scoping review was to<br />

analyze the literature and determine which skills or<br />

characteristics best promote independent living, and create an<br />

assessment protocol that measures these skills.<br />

Methods<br />

The authors employed scoping review methodologies<br />

identified by Arskey and O’Malley (2005) and Levac,<br />

Colquhoun, and O’Brien (2010). This methodology is ideally<br />

suited for topics that have not been examined in detail, that<br />

explore broad research questions, and utilize a wide variety of<br />

study designs (Arksey & O’Malley, 2005). They are also well<br />

suited for summarizing and disseminating research for the<br />

purpose of making policy recommendations (Arksey &<br />

O’Malley, 2005). This scoping review resulted in<br />

recommendations for the ErinoakKids ILP assessment<br />

protocol. The following online databases were utilized to<br />

identify studies pertaining to personal characteristics that<br />

promote successful independent living: MedLine, PsycInfo,<br />

CINAHL, ERIC, AMED, and Embase. Articles were reviewed<br />

for the following inclusion criteria: studies pertaining to youth<br />

with physical and/or intellectual disabilities, focus on personal<br />

characteristics and independent living, peer-reviewed, English<br />

language, published after 1980 and conducted in North<br />

America/Europe. Articles were excluded if they focused on<br />

interventions/programs, or the challenges impeding successful<br />

independent living. Thematic data pertaining to personal<br />

characteristics was extracted and summarized in chart form. A<br />

list of identified personal characteristics was compiled. The<br />

authors identified key personal characteristics based on the<br />

strength of evidence and number of supporting studies.<br />

Suitable assessments measuring the key personal<br />

characteristics were reviewed for psychometric properties and<br />

clinical utility using established guidelines (Law, 2004).<br />

Recommendations were made to revise the current ILP<br />

assessment protocol.<br />

Results<br />

Twelve articles met the inclusion criteria. Results of thematic<br />

analysis highlighted several personal skills and characteristics<br />

associated with positive independent living outcomes. The list<br />

of personal skills identified in thematic analysis included: selfdetermination,<br />

social skills, positive attitude towards future<br />

independent living, higher level of experience in practical<br />

living skills, intelligent quotient, absence of maladaptive or<br />

problem behaviour, self-efficacy, self-esteem, internal locus of

control, and level of physical function. Five articles in the<br />

scoping review summary included self-determination as a<br />

critical skill for successful independent living. Selfdetermination<br />

incorporates self-realization, self-awareness,<br />

empowerment and autonomy (Wehmeyer, Palmer, Soukup,<br />

Garner, & Lawrence, 2007). Four articles demonstrated a link<br />

between independent living and social skills (social problem<br />

solving, peer support, communication, cooperation, assertion,<br />

responsibility, empathy, engagement and self control). Several<br />

assessments measuring social skills and self-determination<br />

were reviewed to determine suitability for the ILP based on<br />

population, purpose of measure, and ease of use. Two<br />

assessments fit the needs of the program, and psychometric<br />

properties and clinical utility were reviewed further. The<br />

revised assessment protocol, including current and<br />

recommended additions is detailed in Table 1.<br />

Table 1. Revised ILP Assessment Protocol<br />

Assessment (Authors) Description<br />

Arc’s Self-<br />

72 item evaluative self-report<br />

Determination Scale* measure that assesses an<br />

(Wehmeyer, 1995) adolescent’s overall level of selfdetermination,<br />

designed for youth<br />

with cognitive, development, or<br />

physical disabilities.<br />

Canadian Occupational An evaluative, semi-structured<br />

Performance Measure interview tool that addresses<br />

(COPM)<br />

occupational performance and<br />

(Law, Baptiste, Carswell, satisfaction in occupation self-<br />

McColl, Polatajko, &<br />

Pollock, 1990)<br />

care, productivity, and leisure.<br />

Goal Attainment Scale An evaluative method for<br />

(GAS)<br />

determining personalized goal<br />

(Kiresuk, Smith, & achievement over time, typically<br />

Cardillo, 1994)<br />

using a five-point scale.<br />

Perceived Self-Efficacy 8 item evaluative self-report<br />

Scale<br />

measure that assesses level of self-<br />

(Chen, Gulley, & Eden,<br />

2001)<br />

efficacy.<br />

Social Skills<br />

An evaluative measure of youth<br />

Improvement System social skills designed to assess<br />

Rating Scale (SSIS- several dimensions of social skills<br />

RS)*<br />

using an optional multi-rater<br />

(Gresham & Elliot, questionnaire format. Self-report<br />

2008)<br />

form includes seven sub-scales of<br />

social skills.<br />

* Recommended additions to the current ILP protocol<br />

Discussion & Implications<br />

The above recommendations for the ILP assessment protocol<br />

will provide ErinoakKids with valid and reliable standardized<br />

assessments. These measures are clinically useful, fit the needs<br />

of the program and assess the key characteristics identified in<br />

the scoping review. In addition, programs similar to<br />

ErinoakKids ILP can include these assessments within their<br />

protocol. The standardized assessments will enable<br />

ErinoakKids to conduct high-quality longitudinal studies with<br />

appropriate outcome measures. The authors recommend that<br />

future research projects compare self-determination and social<br />

skills between adolescents who attend the ILP and those who<br />

do not. Although this scoping review focused on personal<br />

characteristics, the authors recognize the important role of<br />

environmental factors in predicting successful independent<br />

living outcomes. Environmental factors could potentially<br />

impede or improve independent living outcomes. It is<br />

important to recognize the interaction between personal<br />

characteristics, environmental contexts, and the demands of an<br />

individual’s independent living goals. The Person,<br />

Environment, Occupation framework (PEO; Law, Cooper,<br />

Strong, Stewart, Rigby & Letts, 1996) can be a useful tool for<br />

occupational therapists to address barriers to independent<br />

living and capitalize on client strengths. The authors<br />

recommend that future research incorporate the examination of<br />

environmental factors, personal characteristics, and the<br />

occupational demands of transitioning to independent living.<br />

Limitations<br />

Overall, there is limited conclusive research regarding personal<br />

characteristics and independent living. This scoping review did<br />

not exclude studies on the basis of study design or<br />

methodology. Due to lack of updated research, some studies<br />

included within this review used designs that were less<br />

rigorous, such as narrative reviews. While the inclusion of low<br />

quality studies is acceptable for a scoping review, future<br />

research should strive for higher methodological rigour.<br />

Conclusion<br />

This study has presented a review of the literature on skills and<br />

characteristics that promote successful independent living for<br />

youth with disabilities. This scoping review identified that selfdetermination<br />

and social skills are important predictors of<br />

independent living outcomes. The Arc’s Self-Determination<br />

Scale and the Social Skills Improvement System Rating Scale<br />

are recommended additions to the current assessment protocol<br />

at the ErinoakKids ILP.<br />

References<br />

• Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8, 19-32.<br />

• Centre for Independent Living in Toronto. (2012). Retrieved March 29, 2012, from: http://cilt.ca/what_is_il.aspx<br />

• ErinoakKids. (2012). Retrieved March 29, 2012, from: http://www.ErinoakKids.ca/index.cfm?pgID=182<br />

• Healy, H., & Rigby, P. (1999). Promoting independence for teens and young adults with physical disabilities. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 66, 240-250.<br />

• Law, M. (2008). Outcome Measures Rating Form Guidelines. [PDF Document]. Retrieved March 19, 2012, from:<br />

http://www.canchild.ca/en/canchildresources/resources/measguid.pdf<br />

• Law, M., Cooper, B,. Strong, S., Stewart, D., Rigby, P. & Letts, L. 1996. The Person-Environment-Occupation Model: A transactive approach to occupational<br />

performance. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 63, 9-23.<br />

• Levac, D., Colquhoun, H., & O’Brien, K. (2010). Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implementation Science, 5, 69-78.<br />

• Stewart, D.A. Law, M.C., Rosenbaum, P., & Willms, D.G. (2001). A qualitative study of the transition to adulthood for youth with physical disabilities. Physical &<br />

Occupational Therapy in Pediatrics, 21, 3-21.<br />

• Test, D.W., Mazzoti, V.L., Mustian, A.L., Fowler, C.H., Kortering, L., & Kohler, P. (2009). <strong>Evidence</strong>-<strong>Based</strong> secondary transition predictors for improving post<br />

school outcomes for students with disabilities. Career Development for Exceptional Individuals, 32, 160-181.<br />

• Wehmeyer, M. L., Palmer, S. B., Soukup, J.H., Garner, N.W., & Lawerence, M. (2007). Self-determination and student transition planning knowledge and skills:<br />

Predicting involvement. Exceptionality, 15, 31-44.<br />

Acknowledgements<br />