WLW, esteemed history enthusiast, pseudohistory debunker, haniwa purveyor, biggest Ninshubur fan not counting Rim-Sin of Larsa

Catching Elephant is a theme by Andy Taylor

Myths about myths: the case of Enuma Elish

Enuma

Elish (or Babylonian Epic of Creation; alternatively, if you’re into

laughably antiquated terms, Chaldean Genesis) is undeniably among the

most famous Mesopotamian myths, second only to Epic of Gilgamesh in

terms of modern recognition. Marduk and Tiamat might not have the

same degree of popculture presence as Greek gods and monsters, or

even as some Egyptian ones, but they are undeniably far ahead of most

other beings from Mesopotamian mythology in that department, perhaps

with Ishtar as the sole equally famous example.

However,

there’s one huge difference between Epic of Gilgamesh and Enuma

Elish: while the general perception of Gilgamesh is pretty accurate

(eg. two dudes go on wacky adventures, then one deals with the

realization humans are mortal), I’d hazard a guess that solid 90% of

what forms the general opinion about Enuma Elish is wrong.

And

I don’t mean just stuff like Fate associating Enuma Elish with

Gilgamesh (this is far from the worst thing Fate did to Mesopotamian

mythology) or obscure blog posts from teenagers playing games of

pretend. I mean “interpretations” comparable to, say, claiming

Polyphemus represents a vanquished older religion, often pushed by

highly influential writers with large audiences (such as Jordan

Peterson).

Read on to find out what Enuma Elish definitely

isn’t - and what it might have been in the eyes of ancient Babylonians.

I

won’t describe the plot of the myth here in detail separately but in

case you have never read it, a pretty decent translation can be found

here of all places.

Without further ado, here are some of the

myths about the discussed myth which need to be dispelled:

Myth

#1: Enuma Elish is the most ancient account of creation in

Mesopotamian mythology, as well as the standard one.

Enuma

Elish is neither the oldest nor the only known theogonic (eg. dealing

with the origin of gods) text from ancient Mesopotamia. While there

is some disagreement between experts regarding the specific date of

its composition, it is now agreed it is no older than 12th

century BCE and no newer than c. 1060 BCE based on the fact that it

elevates Marduk to the position of the head of the pantheon, but

completely omits his servant Nabu, whose role grew in the first

millennium. It’s therefore possible that it was composed during the

reign of Nebuchadnezzar

I, who brought back the statue of Marduk from Elam (it was taken as

booty after the Elamites overthrew the Kassite dynasty of Babylon),

possibly to further increase the prestige of this victory by

asserting he saved the representation of not just the national

symbol, but the very center of the universe as the Mesopotamians

understood it.

As

for acceptance of Enuma Elish – it undeniably enjoyed a degree of

popularity, however it was not a single defining scripture in the way

holy texts of Abrahamic faiths are. It wasn’t even the only account

of creation involving Marduk!

The oldest Mesopotamian theogony

was instead most likely the so-called “Enlil theogony” also known

as “Enki-Ninki deities” or even “the Enkis and the Ninkis”

(no relation to the water god), known from sites dated to the middle

of the third millennium BCE already. For the most part it was simply

a long list deities, starting with Enki and Ninki (“lord earth”

and “lady earth” - a representation of the primordial element in

this model; the “ki” in the name of the unrelated water god

remains unexplained) and ending with Enlil, the original head of the

Mesopotamian pantheon, and his wife Ninlil. The number of generations

(max. 22, min. 3) and the names of “in between” ones differ from

list to list though there are recurring patterns.

Its

popularity is evident in the fact that names of Enlil’s ancestors

appear frequently in god lists, in exorcisms, and even in some

mythical texts. Enki and Ninki even made their way into Hurro-Hittite

mythology, where under names Minki and Ammunki they appear among the

gods inhabiting the Dark Earth (eg. the underworld), who were invoked

as audience for recitation of epic poems or as witnesses of pacts and

oaths.

In addition to ancestors, some texts also provide

Enlil with an evil paternal uncle, Enmesharra, who presumably tried

to usurp his power or had to be vanquished for Enlil to take the

stage (either by Enlil himself or one of his sons – fragmentary

texts hint as battles between Enmeshara and Ninurta or Nergal). There

were also alternative accounts presenting Enlil as the son of a god

named Lugaldukuga, or simply as the firstborn son of Anu, his fellow

head god.

Anu himself was also provided with a theogony,

likely modeled after Enlil’s: instead of earth it starts with a pair

called Duri-Dari – a hyposthasis of time or eternity. Here too the

number of generations and the names differ, and there isn’t even a

unifying motif like the En-Nin names present. One of Anu’s ancestors,

Alala, deserves a special note – in Hurrian texts, under the name

Alalu, he appears as the father of Kumarbi (the antagonist of the

Hurrians’ very own theogony), deposed by Anu and seemingly not

related to him by blood.

A shared feature of the Enuma Elish

and the Enlil and Anu theogonies is that the individual stages do not

appear to have much of a symbolic significance on their own – this

is taken to the logical extreme with figures such as Engiriš

and Ningiriš

from the Enlil lists, literally “Lord and Lady

Butterfly.”

Renowned assyriologist Wilfred G. Lambert who

dedicated much of his career to the study of Enuma Elish and other

theogonies noted that these texts likely had an important purpose:

establishing that, to put it colloquially, the gods aren’t engaging

in incest by making them descendants of primordial entities who arose

spontaneously. While it might sound unusual due to Greek mythology

shaping our expectations, in ancient Mesopotamia, sibling and

parent-child incest were a taboo which generally extended to the

world of gods, and commentaries indicate that avoiding the

implications of such relationships in the world of actively worshiped

gods was often a pressing issue for theologians working on the Enlil

and Anu ancestor lists (bear in this mind when you see the dubious

family trees floating online).

According to Lambert this

phenomenon can be found in Enuma Elish too to a degree: Marduk’s

mother, Damkina, isn’t listed in the earlier sections of the

theogony, nor is the origin of Anu’s spouse stated; Mummu, Apsu’s

vizier defeated alongside him, isn’t actually referred to as anyone’s

son either. Enlil appears in a small role without his origin being

explained, too.

An exception from this rule is the exotic

text Theogony of Dunnu, known from only one copy and evidently very

late. Here the anonymous author uses a completely random selection of

figures, ranging from Tiamat (here by no means primordial) to an

obscure Hurrian word for heaven and even Dumuzi’s sister Geshtianna

(sic), to tell a tale of incest, murder and debauchery, which

seemingly ends with the birth of Enlil who presumably abandons the

customs of his ancestors, as evidenced by the fact no myth depicts

one of his many children murdering him. Note that unlike many Greek

gods Enlil generally sticks to having legitimate children in known

texts and myths often deal with their visits in his

palace.

Fragments of various cosmogonies were freely

recombined into new ones, sometimes with elements of other myths

incorporated as well: Enuma Elish is simply one example of this.

What’s unique about it is that it’s relatively well preserved, not

its age or popularity in the ancient world. As summed up by W. G.

Lambert, while it’s hard to dispute that Enuma Elish had a large

impact but “the

traditional tolerance and mutual respect of the various cities did

not completely disappear, and even in Babylon itself there were those

who preferred forms of the myth other than those which (…) [Enuma

Elish] tried to canonize.” It’s

also worth pointing out that Enuma Elish was itself treated as a

source of mythical “puzzle pieces” by Assyrian rulers: there are

a few scattered references to Ashur battling Tiamat, and even a few

copies of the epic itself which appear to replace Marduk with Ashur.

Myth

#2: Enuma Elish dates back to the reign of Hammurabi, who wanted to

rewrite religion

Hammurabi,

who reigned in the 18th

century BCE, formed a rather short lived empire which united a number

of city-states and petty kingdoms. He did elevate the status of

Babylon, formerly an insignificant town, and made it an important

player in the next 1200 years or so of the region’s history. However,

little of what he did had much of a lasting impact on religion – as

a matter of fact some researchers go as far as saying that religion

was the only aspect of Mesopotamian culture unifying all individual

ethnic and linguistic groups and states of this region through

ancient times. Wilfred G. Lambert described the situation during the

reign of Hammurabi and his successors in similar terms: “The

old established Sumerian pantheon is still going strong”

What

is undeniable Hammurabi was indeed the first historically notable

ruler to mention Marduk, formerly equally insignificant as his city,

frequently. However, he didn’t place Marduk in a particularly high

place, nor were his actions unique. What he actually did was present

Marduk as a god who intervenes on his behalf to secure support of the

upper echelons of the Mesopotamian pantheon, namely the sky gods Anu

and Enlil. He attributed his victories and reign in particular to

Marduk’s help.

However he acknowledged that ultimately Marduk wasn’t the source of

them: “Anu and Enlil nominated me, Hammurabi, to improve the lot of

the peoples.”

This

has a number of close parallels in Mesopotamian history – Sargon

presented Inanna/Ishtar as his divine benefactor in almost the same

terms, while Gudea of Lagash was rather enthusiastic about the

snake/vegetation god Ningishzida. While there was a political

dimension to it – royal inscriptions could increase the status of a

not necessarily major deity, and as a matter of fact did just that

for both Ishtar and Marduk (though not for Ningishzida, whose

importance only decreased with time) – it was ultimately first and

foremost a manifestation of personal piety. Everyone had a family god

they revered particularly strongly and asked to act as intermediary

between them and the distant kings of gods, some just had more ways

to show it.

Marduk’s earlier history is shrouded in mystery

due to relative lack of importance of Babylon in the 3rd

millennium BCE. What can be said with certainty is that for as long

as Babylon existed, Marduk was its god. Worldhistory.org (formerly

Ancient.eu) presents a completely made up theory that Ishtar was the

goddess of Babylon before Marduk; this finds no support in any

credible publications. “Ishtar of Babylon” was a popular

hyposthasis of her in later times and even had some unique

characteristics, but there is precisely 0 evidence that there was

ever a time when Marduk was not the tutelary god of Babylon.

Save

for this role, which tells us nothing about Marduk’s character since

every settlement had a tutelary god, his early history is impossible

to investigate. Various theories arose nonetheless, for example

presenting him as an agriculture or vegetation god (on the account of

his spade symbol), as a weather god (because the weather serves as a

weapon in Enuma Elish) or as a figure from the circle of the sun god

Utu/Shamash on account of a possible meaning of his name (“calf of

Utu”).

Marduk possibly gained his character as a god of

exorcisms and great sage due to syncretism with Asalluhi, the son of

Enki of Eridu, the third most important god of ancient Mesopotamia;

the exact circumstances of this equation are unknown, though it’s

safe to say that Eridu’s role as a religious center played a role.

Other theories assume both gods played a similar role in different

parts of Mesopotamia, or that the equation took place because of

factors not currently known and unrelated to exorcisms. Whatever the

reason behind it was, it’s important to point out this equation

actually predates Hammurabi’s reign and might have originated outside

the city of Babylon – the first instance has been identified in the

documents of king Sîn-iddinam

of Larsa from 19th

century BCE.

As a side note it’s worth pointing out that while Enki was equally

revered as Enlil and co., he was viewed as more approachable. As

noted by W. G. Lambert: “In

cuneiform literature

generally, [he] is active, never discredited or hated, and an ever present source of help to the human race.” It’s not impossible

that Marduk’s early perception was similar, even though later he

basically fully turned into an Enlil figure.

Much of Marduk’s

prestige cannot be attributed to Hammurabi, also. His rise happened

largely under the long reign of the Kassite dynasty. Kassites didn’t

rule the largest empire ever and weren’t exactly the greatest of

conquerors, but they gave Babylon something very different:

stability, secured with diplomacy and dynastic marriages with the

foremost powers of the era: the Hittite empire, the Mitanni, Elam and

so on. Attempts at pressuring the Egyptians for a similar pact failed

(pharaohs very much enjoyed receiving foreign wives but weren’t

enthusiastic about the prospect of sending own daughters or sisters

abroad), but both states were evidently on reasonably good terms, as

there is some evidence for Egyptian citizens in Babylonia, and many

Egyptian diplomats were fluent in Akkadian.

The Kassite

rulers also turned Babylon into a world-famous (bear in mind this was

a much smaller world) center of arts and learning – a role it

retained for the rest of its history. Their policies were generally

popular, and in terms of the cult of Marduk in particular they gained

renown for pressuring the Hittites to return Marduk’s statue (a

symbol of the city) stolen a few decades prior.

Myth #3: Tiamat represents matriarchal religion suppressed by Hammurabi/Sumerians/whatever

Matriarchal

prehistory filled with cult of “fertility” and “mother

goddesses” is itself a myth, advanced first by Victorian

aristocratic failsons whose “academic” interests boiled down to a

quest for “savage” customs to contrast with the righteous

Victorian way of life.

The author who connected these

Victorian confabulations to Tiamat was Robert Graves, (in)famous for

the creation of the “triple goddess” concept, cheating on his

wife with teenage “muses” and misinterpreting any text he

touched. I already wrote how I feel about Graves in the past so I

will not repeat myself here – it will suffice to say he was wrong.

The rule of Enlil and Anu over the Mesopotamian pantheon is attested

in earliest times already and the most prominent female deities –

Inanna/Ishtar, various mother goddesses, medicine goddesses like

Gula, spouses of major deities etc. - maintained a similar degree of

popularity through most of Mesopotamian history.

Tiamat

wasn’t worshiped and occupied the same niche as other monsters: her

role in cult boiled down to being vanquished by a popular god. She

doesn’t really represent a demonization of anything specific. As I

stated above, preexisting myths were often treated as puzzle pieces.

In her case, the following well attested elements were combined to

create a new antagonist:

- the belief that water, rather than earth or time was the primordial element (not actually all that common in Mesopotamia!); however there’s also a motif from the more common type of cosmogonic myths where earth and heaven are created by splitting a lump of primordial matter

- the Anatolian and Syrian type of myth about combat between an upstart leader of gods, ex. Baal (Hadad) or Teshub, and the sea, personified as an antagonistic god (the most famous and best defined example being the Ugaritic Yam)

- the belief in a body of water where monsters are created or live, sometimes thought to be a river in the underworld called Hubur (note that Tiamat is called “mother Hubur” in the epic); an echo of this belief is particularly strong in passages which describe Tiamat’s monster army as swimming in her waters

- Ninurta’s monster slaying escapades – the number of Tiamat’s minions is even equal to the number of enemies Ninurta traditionally vanquished, and both groups overlap

- myths about

combat between the current gods and their evil ancestors – Enlil is

particularly strongly associated with these, his enemy being his

uncle Enmesharra

As a side note -

Worldhistory.org/Ancient.eu presents a completely baffling theory

that Tiamat was related to Ishtar (or to be precise that she was a

demonization of the latter). This, too, is a product of that site’s

contributors’ imagination: Ishtar’s status after her elevation by

Sargon remained consistent. Antagonistic role in one myth (eg. the

standard version of Epic of Gilgamesh; note it doesn’t even apply to

other versions of Gilgamesh!) doesn’t mean a deity was viewed

negatively, and trying to prove she was regarded as a marginal or

outright demonic entity because of her other characteristics says

more about the authors of such claims than it does about ancient

Mesopotamians.

Marduk’s actual “rival” was

Enlil and his cult center, Nippur – the reason why Marduk receives

50 names is because that was a holy number of Enlil; and to ancient

readers the name-giving ceremony was the clear climax of the story

and ultimate triumph of the hero. Having many epithets wasn’t

unusual, and in fact Ishtar, Nergal and Ninurta all have more

epithets attested than Marduk; however, it was the delivery of them

in Enuma Elish that made them special. It sent a clear message: some

people in Babylon aren’t fond of Nippur and can do all Nippur does

better.

Nippur was never the center of an empire but it was

originally the religious center of Mesopotamia, and played an

important role in royal ideology. The priesthood of Nippur was as a

result rather powerful, as expected from the servants of the single

most significant god and father of many city gods.

However,

there’s evidence that even Marduk and Enlil weren’t necessarily

imagined as hostile towards each other, and the traditions concerning

them as incompatible – in one myth Marduk’s wife Zarpanit is

identified as daughter of Enlil (this is notably one of the only

myths she appears in, and the one which gives her the most

personality); in another, known only from second hand references

currently, Enlil evidently plays a more active role in the history of

Marduk.

Sub-myth:

all myths of the “combat with the sea” variety feature a young

storm god and a serpentine “mother sea”

Tiamat’s

gender is actually an outlier. In all the 4 other most prominent

myths of this variety the sea is male: the Ugaritic Yam, his Egyptian

adaptation Pi-Yam and the Hurro-Hittite Aruna and Hedammu are all

evidently men. As far as I am aware this is simply a matter of

grammatical gender impacting the nature of personifications – the

Akkadian tiamat/tamtum

(sea) is a feminine noun, but the word for sea is masculine in the

other cases.

It’s true that gods fighting the sea are usually

depicted as young, but this has more to do with such myths generally

serving as “backstory” praising the past deeds of a popular

deity. Also, while ex. the Ugaritic Baal was depicted as youthful in

most known sources, Marduk isn’t necessarily meant to be young in

Babylonian imagination, and mythical descriptions of him vary. In the

Epic of Erra, for example, he seems to be a passive old man easily

tricked by Erra (Nergal).

Sub-myth:

Tiamat in Nammu

Nammu

is a rather obscure figure in Sumerian mythology. I noted before that

certain entities existed only as part of elaborate theogonies and

divine genealogies: Nammu fulfilled this function for Enki, and was

seemingly rather obscure outside of a single city, Eridu, where

Enki’s cult had its main center. As Enki was a god associated with

water, his mother shared a similar character. However, neither of

them was associated with the sea, but rather with springs, rivers and

marshes.

Additionally, many references to Nammu don’t really

highlight her possible watery character – she’s

instead presented as a deity associated with exorcisms and related tools such

as censers. In that capacity she continued to enjoy a limited

relevance both before and after Enuma Elish were written.

The

only text to possibly mention both Nammu and Tiamat is of little

value for this discussion as it identifies Nammu as a male figure and

the spouse of Nanše (a slightly less obscure goddess associated with

fish, birds, orphans, widows and dream interpretation, sometimes

viewed as Enki’s daughter or a member of the Eridu pantheon through

other means); this was most likely a mistake. Very old documents

sometimes used the signs for “Engur” (another term for Apsu

understood as a place) to write Nammu’s name which might be the

source of this confusion. Either way, while Nammu was never that big

of a deal outside her hometown, she evidently didn’t morph into

Tiamat as she kept her small role and some sanctuaries long after

Enuma Elish was written.

Myth

#4: Enuma Elish is the origin of monotheism

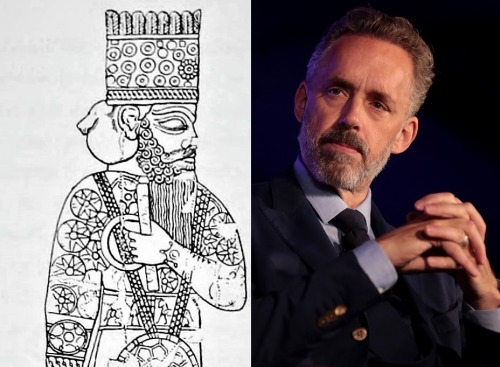

This

is another claim pushed by Canadian online talking head and

pharmacological coma enthusiast Jordan Peterson in between claims

about benefits of an all meat diet and garden variety intellectual

dark web talking points. Like the entire “scholarship” of mr.

Peterson they are worthless. I’m under the impression that many

people see him as some sort of “logic & reason” figurehead

akin to Neil deGrasse Tyson, but in reality he’s basically the male

version of a crystal healer suburban mom. Peterson doesn’t even read

the texts he talks about, he just forms opinions based on Jungian

mysticism, a field whose only positive contribution to culture was

inspiring Persona 1.

Enuma Elish isn’t any more “monotheist”

than many other texts where a specific god is the protagonist, and as

a matter of fact Marduk’s status in its context entirely depends on

other gods, who raised him and bestowed his titles upon him –

hardly a monotheist arrangement!

At best the

“proto-monotheism” argument can be supported by a genre of

syncretistic hymns in which specific deities are turned into epithets

of other ones. Such a hymn to Marduk is known, but it’s later than

Enuma Elish, and shows little, if any, connection to it.

Additionally, given how there are similar texts about Ninurta,

Ishtar, Gula (goddess of medicine) and even Nanaya, a courtier of

Ishtar, some researchers doubt that it’s truly an example of

monotheism: these texts might only be a way to exalt specific deities

by showing them as equal in rank to many other gods. I guess making

monotheism claims about Nanaya, notable for stuff like being invoked

to deal with unrequited crushes and impotence just isn’t cool enough

for authors of the sort discussed here.

Nanaya - not cool enough for monotheism theories? (wikimedia commons)

A

further problem with this claim is the fact that the role of other

gods in the cult of Marduk only grew with time. Nabu became Marduk’s

son and heir after Enuma Elish was written, most references to

Zarpanit are rather late, and a myth from Seleucid(!) times describes

Nergal as Marduk’s valuable ally.

Myth

#5: Enuma Elish represents the new year ritual from Babylon

Enuma

Elish did play a role in the cult of Marduk – a few references in

Assyrian and Seleucid texts confirm as much – but it was distinct

from the Akitu festival celebrating New Year. Enuma Elish was most

likely meant to serve as an “educational” text about Marduk

rather than a cultic one.

It’s possible that the Akitu

festival featured a ritual meant to memorize the battle between

Marduk and Tiamat, but it’s doubtful that it represented the exact

same tradition as Enuma Elish. It’s also worth noting that other

cities had “akitu houses” dedicated to local gods too. Whatever

entity was fought there was more likely to have an infernal than

marine character. W. G. Lambert proposed Enmeshara or a separate

version of Tiamat linked to the underworld rather than the sea.

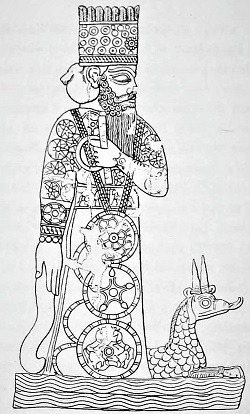

Myth #6: the dragon depicted alongside Marduk is Tiamat.

Marduk and his pet (wikimedia commons)

Many

depictions of Marduk do show a serpentine creature near him. However,

these are unrelated to Tiamat. It’s instead the mushussu, a type of

Mesopotamian dragon attested even before Marduk himself. It served as

a symbol of other gods as well, and in art at times appears as a pet

or mount. Frans Wiggermann, an expert in Mesopotamian demonology,

proposes that Marduk obtained this symbol after Hammurabi’s conquest

of the city-state Eshnunna, whose tutelary gods Ninazu and Tishpak

were also depicted alongside this creature. Marduk’s pet was

evidently benign: “Your

symbol i s a monster from whose mouth poison does not drip,” states

one text.

As for Tiamat, it’s far from certain if she was even

imagined as dragon-like.

She hardly appears outside Enuma Elish, but her descriptions aren’t

really consistent even in the epic itself. She is both a body of

water inside which other monsters can swim, and some sort of large

beast. The notion of Tiamat as a dragon is based on parallels with

other myths about gods battling the sea, but it’s hard to tell if

that’s how Babylonians actually imagined her. Some descriptions

indicate she was simply a body of water; some evidently describe her

as at least partially anthropomorphic; finally some indicate she was

a quadruped of some sort. Some researchers propose a goat or a cow,

but it’s worth noting one ritual formula indicates that “The

dromedary is the shade of Tiamat” - an equation which makes much

more sense in Akkadian, as the dromedary was known as “donkey of

the sea.”

It’s

nonetheless possible to defend the possibility of serpentine Tiamat

as long as you are willing to draw parallels between her and Irhan.

Irhan was yet another primordial watery being, though associated with

a (cosmic) river and male; he was seemingly described as snake-like due to confusion with similarly named mythical snake Nirah.

Irhan is, if nothing else, a closer parallel with Tiamat than Nammu,

arguably. A figure similar to Irhan was Lugal Abba (“king of the

sea”), a poorly known underworld deity.

Closing

remarks

This list is by no means comprehensive. It’s basically

a sample of things I had to witness myself; there are doubtlessly

many other dubious claims making rounds online. I nonetheless hope I

can tilt the balance at least slightly, and I hope my points

illustrate that the genuine article is more interesting than

Peterson’s and other similar authors’ claims.

Bibliography

- The following entries from Reallexikon der Assyriologie und vorderasiatischen Archäologie: Kassiten (Kassites), Lugaldukuga, Marduk, Mischwesen (mythical hybrids), mushussu, Nabu, Nammu, Nin-giri, Sebettu. The online edition linked here is fully searchable.

- Goddesses in Context: On Divine Powers, Roles, Relationships and Gender in Mesopotamian Textual and Visual Sources by Julia M. Asher-Greve and Joan G. Westenholz

- The Other Version of the Story of the Storm-god’s Combat with the Sea in the Light of Egyptian, Ugaritic, and Hurro-Hittite Texts by Noga Ayali-Darshan

-

Foreigners in the Ancient Near East by Gary Beckman

- “Enlil and Namzitara” Reconsidered by Jerrold S. Cooper

- Ishtar

seduces the Sea-serpent. A New Join in the Epic of Hedammu (KUB 36,

56+95) and its meaning for the battle between Baal and Yam in Ugaritic

Tradition

by Meindert

Dijkstra

- My

neighbor’s god: Assur in Babylonia and Marduk in Assyria

by Grant Frame

- Some Remarks about the Beginnings of Marduk by Anreas Johandi

- Babylonian Creation Myths

by Wilfred G. Lambert (not available online but I can figure something out if you’re interested)

- Mesopotamian Creation Stories by Wilfred G. Lambert (see above)

- A Reconstruction of the Assyro-Babylonian God-lists, AN:dA-nu-um and AN:Anu Ŝá Amēli by Richard L. Litke

- A Hymn to Noisemaking and Namegiving: Assyriological Viewpoints on the Meaning of Enūma Eliš by Seth L. Sanders

- The Fifty Names of Marduk in Enuma Elish by Andrea Seri

- On ym and A.AB.BA at Ugarit by Aaron Tugendhaft

- Agriculture as Civilization: Sages, Farmers, and Barbarians by Frans Wiggermann

- Mesopotamian Protective Spirits: the Ritual Texts by Frans Wiggermann

- The Mesopotamian Pandemonium by Frans Wiggermann

- Tišpak, his seal and the dragon mušḥuššu by Frans Wiggermann

- Transtigridian Snake Gods by Frans Wiggermann

viridiansindria liked this

viridiansindria liked this  akishounen liked this

akishounen liked this  nekiddo liked this

nekiddo liked this  oldonesorceress liked this

oldonesorceress liked this enthusiastofshit reblogged this from yamayuandadu

apocalypticautumn liked this

actually-the-antichrist reblogged this from yamayuandadu

mistoffeleesisawitch liked this

despoiledshore liked this

senthesnail liked this

kunstkamera1714 liked this

fatenumber4ever reblogged this from yamayuandadu

vvixxxi liked this

mirum-somniavi-somnium liked this

mirum-somniavi-somnium liked this elfenphoenix liked this

hoohoobitch reblogged this from en-theos

hoohoobitch reblogged this from en-theos  hoohoobitch liked this

hoohoobitch liked this triumviir liked this

latinisnotadeadlanguage reblogged this from yamayuandadu

latinisnotadeadlanguage liked this

sbhelarctos reblogged this from yamayuandadu

dapurinthos liked this

malindulo reblogged this from yamayuandadu

malindulo reblogged this from yamayuandadu breitzbachbea reblogged this from yamayuandadu

kittychan-sings-enka liked this

lunar-monster liked this

breitzbachbea liked this

malindulo liked this

malindulo liked this lorchidae liked this

en-theos reblogged this from godlovesdykes

en-theos liked this

the-puffinry liked this

iphis-et-iante liked this

sophisotes reblogged this from yamayuandadu

sophisotes liked this

mileschristiregis reblogged this from godlovesdykes

mileschristiregis reblogged this from godlovesdykes darning-needle-dragonfly liked this

starofashtree liked this

godlovesdykes reblogged this from yamayuandadu

wantshapesthem reblogged this from aethergeologist

wantshapesthem reblogged this from aethergeologist primalwarden liked this

warden-to-vacancy liked this

poppy-girl95 reblogged this from aethergeologist

poppy-girl95 liked this

aethergeologist reblogged this from zenosanalytic

graveyard-mouth liked this

graveyard-mouth liked this  crazystrawberry9102 liked this

crazystrawberry9102 liked this aethergeologist liked this

yamayuandadu posted this

yamayuandadu posted this - Show more notes