The Catwalk is No Cakewalk: Example of Execution Excellence

Posted: September 16, 2012 Filed under: Creative, Unusual, Amusing, Performance improvement | Tags: execution, fashion, fashion shows, fashion week, planning, process excellence Leave a commentWhat we see on TV or in magazines does not begin to convey the extent of precision planning and rigorous process that goes into a fashion show. Many years ago I had an unusual assignment which was to help a client develop and improved buying process for women’s wear. Consequently I gained a first-hand appreciation of the level of detailed planning and honed processes that went into things like the buying process, the merchandising process and the shows clothing makers put on for the buyers, opinion makers, celebrities and the rest of us.

This past week was the first of four, grueling, back-to-back event called the New York, London, Milan and Paris Fashion Weeks. For New York’s Fashion week, Ben Schott takes us inside the unseen processes behind these events.

Twice a year (February and September) Fashion Weeks are hosted by four cities. Below are the 2012 dates for the Spring/Summer 2013 lines:

Sept. 6 – Sept. 13 NEW YORK

Sept. 14 – Sept. 18 LONDON

Sept. 19 –Sept. 25 MILAN

Sept. 25 – Oct. 3 PARIS

New York was last on the schedule until 1999, when designers, including Helmut Lang and Calvin Klein, succeeded in flipping the city to first. In part this reflected the power of the U.S. market; in part it was to counter accusations that American designers copied European shows.

During the eight days of NEW YORK FASHION WEEK more than 300 shows will be held. Eighty or so are part of Mercedes-Benz Fashion Week, held in Lincoln Center; about 40 are part of Made Fashion Week at Milk Studios, Chelsea; the rest are in OFF-SITE locations across the city.

SCHEDULING

With so many designers competing for locations, models and (crucially) an audience, SCHEDULING is key. To facilitate this, New York turns to the FASHION CALENDAR – which, since the 1940s, has listed every Fashion Week event from runway shows to cocktail parties. The FASHION CALENDAR is still edited by its creator, Ruth Finley, who acts as an unofficial gatekeeper for new designers and the industry’s mediator for scheduling conflicts. This year, the calendar runs to 25 pages, but the week’s key events are compressed into a single-page GRID – an examination of which offers insights into the rhythm of Fashion Week. For example: lesser-known designers often show in the first few days, before the major shows start; morning shows tend to be about business, and evening shows about the “scene”; international designers often wait until the weekend, when European V.I.P.’s fly into the city; and the week’s final big show (Calvin Klein’s women’s collection, 3 p.m.) ends in time for the evening flights to Europe.

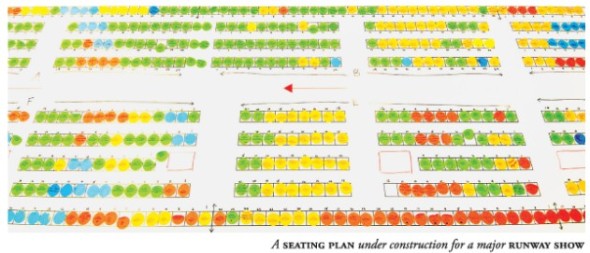

SEATING

Seating a RUNWAY SHOW is an artful mix of showmanship and diplomacy. Who is seen in the audience can add significantly to a designer’s reputation and a collection’s coverage. Equally, seating friends, enemies and frenemies is an exercise in tact. There are three powerful audience groups: EDITORS, BUYERS and CELEBRITIES. Each has its own hierarchy, rivalries and politics, and each looks, in part, to the others. For example, at the show of a new designer, BUYERS will note the presence of major EDITORIAL figures, and vice versa. And at the show of an established designer, the absence of a major BUYER might raise eyebrows. CELEBRITIES are media catnip, and BOLD-FACE NAMES can dramatically increase press attention. (Fashion-forward actresses please heavyweight and trade publications; reality stars please the weeklies; and A-listers please everyone.) Some celebrities are friends of the designers and wear their clothes; others are paid to attend.

To the cognoscenti, just the first three rows of seating matter. The FRONT ROW is the only place to seat V.I.P.’s – which sometimes explains the preference for U-SHAPED runways that have more front-row seating. V.I.P.’s expect to be seated next to people of equal or greater status; thus the FRONT ROW becomes integral to the show when captured by the photographers. (Last year, guests in the FRONT ROW of the Ralph Lauren show were asked to move their handbags so they would not clutter the runway photographs.)

There is an elite group of highly influential commentators for whom, if they are running late, many designers will HOLD THE SHOW, including: ANNA Wintour, editor of Vogue; SUZY Menkes, fashion editor of The International Herald Tribune; and writers from The New York Times, Women’s Wear Daily and Style.com.

V.V.I.P.’s are seated in prime position along the FRONT ROW, for example two-thirds down a straight (OUT AND BACK) runway – a vantage point that allows ample time to see the front and back of each LOOK. Less senior members of an editorial or buying team can be arrayed in the SECOND or THIRD ROWS, but the rows beyond that – SIBERIA – are seldom to be tolerated. (Stories abound of people demanding upgrades, refusing seats they deem insulting, and storming out of shows. Non-V.I.P.’s sometimes sneak into vacant front-row seats moments before shows start.)

Influential bloggers are increasingly considered V.I.P.’s, both because of their online following and their immediacy – especially compared with LONG-LEAD monthly magazines.

LOOKS CASTING

Fashion shows are constructed in many ways; the following is one example.

A DESIGNER works with a STYLIST to focus a COLLECTION into a series of LOOKS that constitute the SHOW. This process often involves a LOOK MODEL upon whom different combinations of clothes and accessories are tested. The LOOK MODEL can be the designer’s MUSE or a FIT MODEL whose proportions suit the designer’s style. (The number of LOOKS in a SHOW varies; most have between 20 and 40, though some have as many as 80 or 90.)

Integral to the creation of the show is the HAIR AND MAKEUP TEST. Here the LEAD (or KEY) HAIR and MAKEUP artists work with the designer and stylist to establish the show’s character.

While the designer and stylist work with PRODUCERS and TECHNICIANS to create the look, feel and sound of the show, a CASTING DIRECTOR is tasked with finding models.

Casting directors generally work on a number of shows and are always scouting for models to suit a range of designers. To that end, aspiring and established models have GO-SEES with casting directors. As shows loom closer, PRE-CASTINGS narrow a selection of models to be presented to the designer and stylist.

Casting involves arbitrage with model AGENTS. Casting directors will request an OPTION (FIRST or SECOND) for each model – a tentative booking that allows both sides to hedge their bets. Directors want the best models for their shows; agents want the best shows for their models. Fees are negotiated, schedules juggled and the shows get cast.

After casting, FITTINGS are held to match each LOOK to a model and adjust the clothes accordingly. (Attending a fitting, however, does not guarantee a model will appear in the show.) Fittings conclude with ROTATION, where the ORDER of the LOOKS is finalized, both to establish the narrative of the show and to allow changing time for models with multiple LOOKS. Fittings and re-fittings take place in the days and hours before a show, placing further pressure on the schedules of popular models.

BACKSTAGE

A show’s CALL TIME is usually two to three hours before it starts, though models are regularly delayed by prior shows, or traffic. Once CHECKED IN, models are grabbed by HAIR and MAKE-UP, whose stylists erase any evidence of previous shows and recreate the CONCEPT finalized at the HAIR AND MAKEUP TEST. (Most shows have a uniform hair and makeup style for every model; early-arriving models are used by the LEAD stylists to DEMO the processes to their teams.) During hair and makeup, the models are summoned for a REHEARSAL, where the show’s choreography and structure are explained.

So that the clothes are not damaged or creased, dressing happens only minutes before the show begins, when “FIRST LOOKS” is called. Models go to the rack labeled with the COMP CARD that displays their name, picture and vital statistics. There, DRESSERS help them assemble the LOOK to match exactly the reference pictures on the DRESSER CARDS.

Once dressed, the models can be photographed for the LOOK BOOK that forms the show’s record. Then they LINE UP in the order they will WALK, for final adjustments and words of encouragement. (Some designers display inspirational posters backstage – e.g., “you’re a confident, sexy, fun woman!”) Finally, in synch with the music, the models are sent out: GO! … GO! … GO!

THE SHOW

Models walk the runway in the style they have been given (“bright,” “confident,” “stoical,” “no smiles”) – and, if instructed, STOP in front of the photographers. (The photographers are usually warned how the models will walk and whether they will stop.) Models with more than one LOOK make a quick CHANGE before going back out.

The number of LOOKS shown at any one time depends on the length and layout of the runway and the choreography. The tradition of runway shows is to OPEN and CLOSE with the STRONGEST LOOKS – worn by the best models.

The style of FINALE varies by designer. Some send out every LOOK at once, others send just a few. If designers take a bow, some are shy, others exuberant; certain designers walk (or cartwheel) down the runway, alone or with their models. Backstage, designers are often greeted with applause.

Runway shows seldom start on time and are not usually considered LATE until 20 minutes or so after schedule. For all their planning, pressure and controlled chaos, most shows last just 10 to 15 minutes – and savvy spectators can be off to the next event before the applause has died down.

Not all shows involve a runway. Some designers host PRESENTATIONS in which the models are (to a greater or lesser extent) static and the spectators come and go. PRESENTATIONS tend to be cheaper to stage, more informal and flexible for the audience, who can visit them between shows. (However, the duration of PRESENTATIONS – usually an hour or two – seldom endears them to models in heels.)

Once displayed, the clothes that formed the LOOKS become SHOW SAMPLES that can be sent around the world for magazine shoots or worn by stars down the red carpet. Emerging designers might sell their SAMPLES to raise money; established brands typically archive them.

MODELS

What models are paid for runway shows varies tremendously, but the following is a guide:

Inexperienced = $0–bags, shoes, etc.

New faces = $1,000–$1,500

Editorially important = $5,000–$10,000

A-list/Marquee = $20,000–$25,000

Thus top models can earn between $100,000 and $200,000 during a Fashion Week and between $400,000 and $800,000 in a season (unless they sign exclusivity deals, for which they are remunerated).

That said, some designers are notoriously parsimonious – and get away with paying little (or nothing) because of their reputation. Conversely, models can walk for free, or reduced rates, for their friends.

SUPERMODELS (SUPERS) exist in an entirely different orbit. If they walk runway shows at all, it is usually because they are friends with a designer, contractually obliged by a wider brand relationship or paid handsomely.

Model agents usually take up to 20 percent from their client and an additional 20 percent from the designer.

Popular models typically appear in a number of shows, which inevitably creates tight deadlines. While most designers are happy to accommodate models’ schedules, some try to LOCK OUT the competition with unnecessarily early CALL TIMES. This brinkmanship is not just an issue within a single Fashion Week. Last year, designers in London were upset when a number of models left the city early for castings and fittings in Milan.

THE PICTURES

Paparazzi aside, there are three (occasionally overlapping) groups of fashion show photographers: those who shoot BACKSTAGE; those who shoot the FRONT ROW; and those who shoot the COLLECTION – the RUNWAY PHOTOGRAPHERS. (There is a fourth group, though it has just one member. BILL Cunningham of The New York Times is so beloved that he is often seated in the front row, and shoots what and where he likes.)

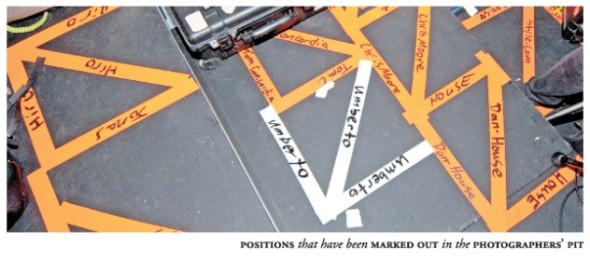

Designers employ HOUSE PHOTOGRAPHERS to document their shows. These photographers scout the location to test the brightness and color temperature of the lights and help MARK OUT (with colored tape) standing POSITIONS on the floor of the PHOTOGRAPHERS’ PIT. Space in these PITS is tight, and etiquette demands that photographers remain in their (foot-square) spots, tuck in their elbows and ensure their lenses do not swing from side to side. MAIN SPOTS in PRIME POSITION are reserved for the HOUSE and for those shooting for major publications. If territorial skirmishes occur, they are settled by the house photographer or the production team. That said, there is a community of seasoned runway photographers who respect an unwritten pecking order and are accustomed to working in close proximity, show after show.

Unless they are tasked with photographing details, like shoes or accessories, the goal of the runway photographer is to capture FULL-LENGTH pictures of every LOOK. The best shot is sharp and uncluttered, and with the clothes and model displaying a GOOD LINE. Ideally, the model’s eyes will be open and her front foot will be down and flat.

Runway photographers tend to use 70-200 mm zooms, or 300 mm prime lenses – often attached to monopods. Like sports photographers, they shoot at a wide aperture (f 2.8) to soften the background and a fast shutter speed (at least 1/250th of a second) to freeze the action. Some photographers will pick a spot along the runway and blast the motor drive when each model comes into frame. Others will zoom out as each model walks toward them, taking a picture with every step. Photographers usually capture 10 to 15 frames per LOOK and can shoot 2,000 pictures in a show. Nowadays, nearly everyone uses digital cameras; some shoot in the highest-resolution RAW format, though – because of limitations in storage and processing time – most shoot JPEGs.

Boxes are used to elevate photographers standing farther from the stage; those who arrive with tripods, flash or stepladders risk being called TOURISTS.

The setup for video matches that for stills. Yet, while videographers are currently outnumbered by photographers, their importance is rapidly growing, especially given the demand for live Webcasts and online clips of shows.

* * *

As New York Fashion Week closes, designers start planning their next collections, and editors, buyers, models and photographers begin to pack. After all, London Fashion Week opens the very next day.